At first glance, a former CIA counterintelligence officer’s post-war trajectory from spy games in the Middle East to a star-making run as a Marvel and DC Comics writer might seem, at the least, sort of random.

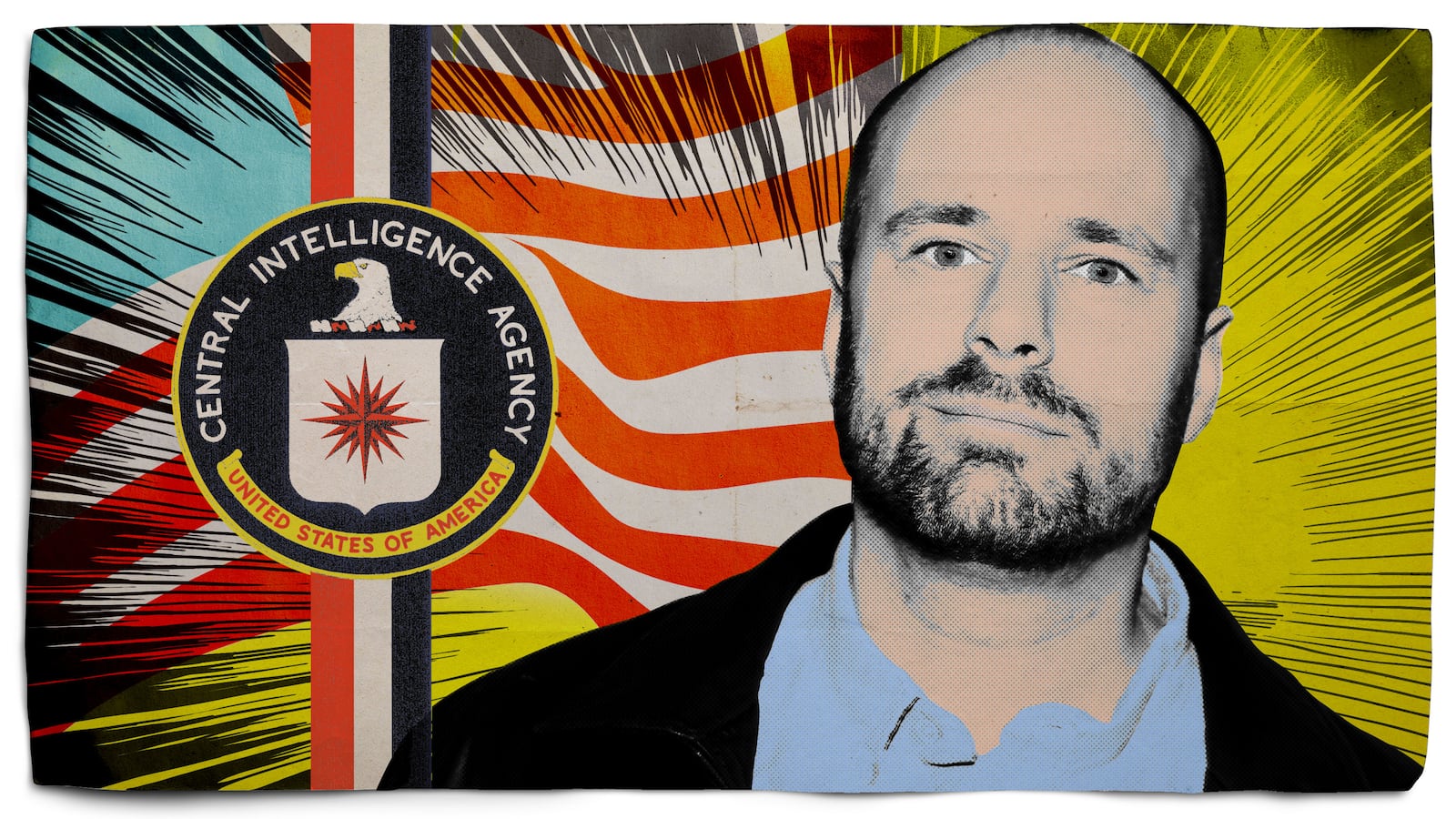

But Tom King, the multiple Eisner award-winning writer of two of the decade’s best comics—Marvel’s The Vision miniseries and DC Comics’ Mister Miracle—indeed served abroad in Iraq and Pakistan on behalf of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center in the years after 9/11. And once back in civilian life, he indeed became one of the comics industry’s most sought-after storytellers, known for expressing the low-level unease of being alive with emotional resonance, efficiency, and frequent doses of gut-punch wisdom.

In Vertigo’s The Sheriff of Babylon, a globe-sprawling series set in post-invasion Iraq, he vented a war’s worth of frustration at the “bullshitting” he witnessed from the inside out. In Marvel’s The Vision, he told a haunting story about family and a universal need for acceptance—using a cast of androids, no less. DC’s The Omega Men was nominally about superheroes in an intergalactic conflict. But really, it was about the impossible murkiness of our world—about religion and terrorism and the futility of war, and how simple it can be to root for the wrong cause. “It sold nothing,” King jokes.

Just three years into his full-time comics-writing career, in 2016, King landed DC’s biggest title, the one about the guy in a batsuit. His Batman run ignited a nerd-world maelstrom when Bruce Wayne’s long-promised wedding to Catwoman ended with the bride-to-be ditching him at the altar. The New York Times spoiled the twist early in its wedding vows section and an aghast King weathered tweetstorms—and death threats—from pissed-off fans for months. “There used to be a bounty on my head from the fucking Taliban—I can deal with a few Twitter followers,” he told Polygon at the time, with the towering bodyguard his jittery agent assigned to him at a convention in tow.

King’s tenure as custodian of Gotham’s favorite son will cut short 15 issues shy of his promised 100-issue run later this year—not due to creative issues, but because King is now busy helping pen director Ava DuVernay’s New Gods movie, adapting the mad cosmic world Jack Kirby dreamed up in the ’70s. More of his work is soon coming to the screen, too: a dystopian TV project dubbed States of America, plus another “secret TV thing” that has yet to be announced. (Bat-fans need not worry: the ending King originally intended for his Gotham-set saga will be repurposed as a Batman/Catwoman standalone miniseries early next year.)

He’s riding the kind of career high comics creators dream of—welcomed by Hollywood, the toast of the comics world. (At San Diego Comic-Con, where the Eisner Awards are handed out, King was this year’s most-nominated creator in attendance. He walked away with Best Writer for the second year in a row, and his and artist Mitch Gerads’ masterpiece, the limited-series Mister Miracle, claimed all three prizes it was up for.)

King’s writing might have struck a chord in any decade. But it’s Mister Miracle that, perhaps more than his other work, speaks expressly to the feeling of this moment in time: the nagging suspicion that reality is too strange to be true; the fear of being trapped in it, or inside your own head; how joy and mundanity mingle here with existential threats and the absurd; and ultimately, how each of us must choose how to live with it.

He took a character of Kirby’s invention, a god and escape artist named Scott Free, and centered him amid mythic forces of good and evil that amount to set dressing in a story about how hard it is to be a person. (Let alone a new father, as King was when he left the CIA and as Scott becomes by Mister Miracle’s end.) King has lived with PTSD and depression of his own; he does not pretend that Scott, even by the series’ end, can be “cured.” But that’s the point. “That’s what makes you live, right?” King tells me. “It’s still a part of you. And it’s not part of you in a bad way. To be alive is to have this.”

King applied to join the CIA almost immediately after 9/11. He was working at the Justice Department in Washington, D.C. when terrorists hit the Pentagon. From then on, as he tells the story, he wanted to be “one of the people who helps out.”

Comics had been a refuge for him as a shy, sometimes bullied kid growing up in Los Angeles. He hoped one day to write them. While a student at Columbia University, he interned at DC’s Vertigo imprint and at Marvel Comics, where he was an assistant to celebrated X-Men writer Chris Claremont. But by the mid-’90s, the comic-book market crashed spectacularly and left the industry’s future in serious doubt. At a time when it seemed possible that there might not be a Marvel or DC Comics much longer, King turned to more stable job prospects. He thought of going to law school. And then he became a spy.

“I loved that job,” King says of his six and a half years with the CIA, hands stuffed in the pockets of a Batman logo-emblazoned hoodie, soft-spoken but grinning when we meet in Chelsea. “I was good at it, too. I was super proud of it. I have very few skills, but I can get one terrorist to spy on another.” For four and a half months, he was stationed in Iraq; he spent a year on the job in Pakistan, too. It was the part of the job he liked best: being overseas, “especially in war zones.” In a photo taken in 2004 in front of Baghdad’s Swords of Qādisīyah arches, King stands with shoulders squared, feet spread apart, clutching an assault rifle. In loose-fitting, dirt-stained jeans (and a slightly fuller head of hair), he looks tough if vaguely, irrepressibly dorky—a geek who can kill.

In Mister Miracle, Scott and his wife Big Barda fight to quell a war between the hellish planet of Apokolips and the benevolent realm of New Genesis. It might be the last thing you end up remembering about the story, though. King and Gerads instead ground the book in Scott’s state of mind—his boredom, hopes, claustrophobia, and wryness as he heaves himself through everyday life. To him, the mission to keep the Anti-Life Equation (an all-powerful, mind-controlling MacGuffin) out of his sinister adoptive father Darkseid’s hands is both a universe-saving mandate and the equivalent of just his day job. The harder thing, for Scott, is living with the scars his years under Darkseid’s stewardship imprinted on his psyche.

King’s own anxiety informed his idea of Scott Free, an escape artist who can’t get out of his own head. “The book started when I had one of those first-episode-of-the-Sopranos panic attacks and I ended up in the hospital,” he says. “It was one of those things where you ask the doctor, ‘Am I dying or am I crazy?’ And they tell you you’re crazy and you’re like, woo-hoo! Oh, wait a second.” He laughs. “I thought I was a pretty tough guy. I’d been to war twice, I’d had three kids. In my own little nerdy corner of the world I was pretty successful. But there was something brittle inside of me.”

Mister Miracle was his chance to write about those brittle parts—and about the creeping suspicion in the age of Trump that reality is fundamentally, metaphysically even, coming undone. “We live in a time of anxiety right now and we gotta acknowledge this at some point,” he says. He starts and abandons several thoughts mid-sentence until, in revved-up emotion, he utters “fuck it” and plows ahead: “I don’t care if I’m political. What the president is putting out there is reflecting on everybody. And the people who are angry at the president have that anger, and the people who get their anger from the president have their anger, and there’s nowhere for that anger to go except at each other, or inside, and we’re all living with that everyday.”

Anger strains the “little cracks” inside a person, he says. “It finds your weak points and makes them worse. How do we live our lives with that?”

King opens the book in the minutes after Scott Free’s failed suicide attempt. By its final panel, whether the reality we’ve witnessed is authentic or not is left unanswered, both to Scott and to us. Artist and colorist Gerads peppers pages with small moments of dissonance: Scott remembers his wife’s eyes being blue, though they are brown—except in the first issue’s second-to-last panel. Only flashbacks to Scott’s feats of escape are narrated as if by a booming TV announcer, yet moments from everyday life seem to glitch, too, blurring scenes like a skipping VHS tape. The effect is purposely jarring—a reminder of how trapped Scott feels.

The image distortions, originally Gerads’ ideas, mimic a familiar feeling for King. “To me it’s like that moment when you’re having a great day and you’re going, well, I’m just going to pick up my phone and check Twitter and read the news,” he says, smiling at the self-own. “And you’re like, oh, I’m still in this goddamn—the awful continues, you know? I’m still trapped in this weird reality.”

He likens the sensation to the way the world seemed to tilt after 9/11. “We were like, wow, something just happened that we’ve never seen happen before. It felt like a break from reality,” he remembers. “And then it felt like we just gathered ourselves and kind of found a new normal and were living in it. And now it’s like we break every day.”

The most inspired moments in Mister Miracle relegate the physical war against Darkseid to the background, often literally.

In one sequence, Scott and Barda deflect lasers, wade past freakish sea monsters, and take out armed guards as they break into Apokolips. They spend the entire scene—nine-plus pages—discussing little more than the cons and merits of decluttering their condo. After Scott is sentenced to be executed in a rigged trial, they spend a day at the Santa Monica pier, then stuck in traffic, shooting the shit in the comfortable banter of a long-term couple. And Darkseid’s most memorable transgression, apart from being an evil warlord, is double-dipping a half-bitten carrot in a veggie platter’s ranch tray.

They’re unremarkable events unfolding in heightened, surreal circumstances; sometimes touching, funny, or grim. The juxtapositions are essential to King, who likens the scenes to the memory of debriefing a source in Iraq in 120-degree weather. “We were both sweating and talking about a guy getting his head chopped off. It was horrible,” he remembers. “But it was my wife’s birthday.” He recalls shuffling into a corner, calling his wife, and singing “Happy Birthday” in half-hushed tones. “That’s what life is, right? The mundane lives right next to the crazy.”

King resigned from the CIA after his wife gave birth to their first son. “I couldn’t be that guy who was at the office 13 hours a day and going overseas all the time,” he says. “I couldn’t be the father I wanted to be and the officer I wanted to be.” So he became a “house dad,” cranking out his first novel in his spare time. A Once Crowded Sky, about the last superhero in a world suddenly bereft of them, debuted in 2012 to strong reviews and middling sales. Still, it recommitted King to his early ambition of penning superhero sagas of his own.

His comic-book debut came in 2013, with a short story titled “It’s Full of Demons” in the Vertigo anthology title Time Warp. Three fruitful years later, he was writing Batman. “Superheroes today are what Westerns were in the ’50s,” he figures. “It’s almost become a common mythical language between all of us. John Ford or Howard Hawks, they could take that Western trope and start to transcend the clichés by building upon them. I think it’s up to people who work in this genre to take that basic format and personalize it, but also be ambitious about it, try to address the great themes of our life.”

Part of Mister Miracle’s ambition is to capture a feeling many know intimately, but which can be hard to put into words. King and Gerads articulate that dread succinctly, often with a single phrase: “Darkseid Is.” Panels black out without warning, flashing the phrase in typewriter lettering. It interrupts moments of loneliness or disassociation. But it can also be a punchline, or a shrug: When Big Barda says it, for example, she could just as well say “shit happens.”

“I was obsessed with making people uneasy while they read the book,” says Gerads, a two-time individual Eisner winner for his work on Mister Miracle. “You force the reader to stop reading and consider the weight of that panel, and it lasts as you continue reading.”

A DC web comic artist named Julian Lytle introduced King to the phrase, the writer explains. “He was like, do you ever feel like you walk out and just can’t take another step, you have to turn around and go back? That’s Darkseid Is. Or do you ever have two choices and you know what the right one is but you make the wrong one anyway? That’s Darkseid Is. Your belly drops and you get a lump in your throat and you can’t breathe and all of a sudden, you feel the evil of the world creep up on you. You’re aware that you’re stuck on this planet, stuck in this situation and you can’t get out. And ‘Darkseid Is’ is that feeling.”

In the story’s final frame, Scott peers out playfully from a “Darkseid Is” panel, his grinning toddler clinging to his leg. He’s chosen to accept the reality he exists in, whether it’s manipulated or a dream, and to live, despite the darkness that threatens to swallow him. Darkseid still is, and Scott Free cannot escape that. No one can. But, King says, “You can’t just be buried underneath it. You have a duty to your family, you have a duty to your job, you have a duty to keep fighting.”

“We have to,” he says. ‘There’s no choice.”