When a former Navy SEAL with ties to a raft of Trumpworld figures landed in Haiti nearly a decade ago, his putative mission was to lead raid and rescue operations that would recover a missing American child. But by his own account, he did little work in that direction—and The Daily Beast has discovered he instead fell into the Caribbean state’s thorny politics, and into an unbelievable business deal: control of a paradisiacal island that Port-au-Prince seized from its inhabitants.

Since Dave Lopez left the elite special ops force, his résumé has featured a stint with Erik Prince’s mercenary firm Blackwater, the launch of an anti-vaxx supplement company, and multiple ventures with former Trump Customs and Immigration Services chief Ken Cuccinelli. But the gig that sent him to Haiti, that entangled him with Port-au-Prince’s powerbrokers, and positioned him to win the rights to build what his team vows will be the struggling country’s answer to Disney World, was his role at Operation Underground Railroad (O.U.R.).

O.U.R. and its founder, Tim Ballard, became nationally famous last summer with the release of its fictionalized cinematic origin story Sound of Freedom—and then infamous in the fall, as Ballard faced claims of sexual predation and of self-enrichment at the expense of his organization’s donors. Ballard has cast these allegations as a “smear campaign” designed to besmirch his name and extort cash.

But in years past, Ballard and O.U.R. had enjoyed a level of celebrity on the political right, where their mission of disrupting alleged child-trafficking networks resonated with a fringe inflamed with conspiracy theories about elite pedophiles dominating the world.

Experts on exploitation warned that the group’s flashy tactics, which included filmed sweeps of supposed underage sex dens, served the self-styled saviors more than the victims. But Ballard developed tight ties with Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes and with then-Sen. Orrin Hatch, secured an appointment from then-President Donald Trump to a new council on human trafficking in 2019, and—according to conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt—enjoyed the personal imprimatur of Trump National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien.

Sound of Freedom dramatized a 2013 raid in Colombia, in which Dave Lopez reportedly participated. But in Ballard’s own telling, O.U.R.’s real birthplace was several hundred miles north, in Haiti.

The head of O.U.R.’s operations in Haiti was Lopez. The ex-SEAL also served as Ballard’s lieutenant in another of his signature projects, the Glenn Beck-founded Nazarene Fund, formed to rescue Christians from persecution in the Middle East. And later, it was Lopez who gave up information to investigators in a probe that led to Ballard’s public disgrace.

But by that time, the contacts Lopez had made through O.U.R. had already secured him power over the island of Ile-à-Vache. He did not respond to repeated outreach from The Daily Beast for this story.

“Gardy is the kid whose story created Operation Underground Railroad,” Ballard asserted in the 2018 documentary Operation Toussaint.

The remark referred to Gardy Mardy, a Haitian-American boy from Ballard’s home state of Utah, abducted in Port-au-Prince in late 2009, whose father, like Ballard, is active in the Church of Latter Day Saints. The film describes a 2014 raid on a location where Ballard believed traffickers were holding Gardy, and depicts subsequent trainings and operations ostensibly aimed at rescuing him and other child sex slaves in Haiti.

Besides Ballard, Operation Toussaint heavily features Lopez, Beck, Attorney General Reyes, and Sen. Hatch—as well as several of O.U.R.’s political allies from Haiti. What it does not feature is the event that made Gardy Mardy so hard to find—the earthquake that devastated the country just weeks after his disappearance.

The political aftershocks of that disaster reverberated throughout the country—even to Ile-à-Vache, six miles detached from the southwest city of Les Cayes. Barely a year later, a contested presidential election ushered U.S.-backed candidate Michel Martelly, a pop star and son of a Shell Oil executive, into the presidential palace.

Former Haitian President Michel Martelly

Hector Retamal/Getty ImagesWith hundreds of thousands of Haitians dead and more than 1 million displaced and injured, Martelly’s priority was rebuilding the nation’s obliterated economy. He and his Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe broadcast the slogan “Haiti Is Open for Business.” And the business best positioned to draw in foreign dollars, they decided, was tourism.

In Ile-à-Vache’s salt-white beaches and teal water, the new government saw a destination that could rival the resorts that had so enriched the neighboring Dominican Republic. The only possible impediment was the island’s 14,000 residents, most of whom worked in fishing or small-scale agriculture.

“Haiti is to a large degree a dependency, whether one likes it or not, of the United States,” observed Dr. Robert Fatton, a Haitian-born professor of foreign affairs at the University of Virginia. “They were bent on transforming the island into a tourist resort. The people living on the island were not consulted at all.”

Fatton noted that Martelly triangulated between the U.S. and its rivals in the region, most notably Venezuela, which dispensed tens of millions from its PetroCaribe program to subsidize Haiti’s tourism ministry. The development of Ile-à-Vache soon became the Martelly government’s signature initiative. The seed for the new, island-spanning project was to be Abaka Bay, a hotel on Ile-à-Vache’s northwest tier, co-owned by an American citizen and his Haitian in-laws.

From the outset, Fatton said, there were rumors of corruption.

“There was protest, and there was also suspicion that Martelly, Lamothe, and company had a financial interest in the project,” the professor remembered, noting that such arrangements have recurred frequently in Haitian history.

The allegations have since become explicit: in an open letter to Martelly published in 2014, Abaka Bay’s American co-owner Robert Dietrich accused the then-president of trying to “horn in” on the project.

Dietrich sent The Daily Beast communications and proposals which he asserted came from Martelly’s intermediaries, which he said he began receiving almost immediately upon the president’s assumption of power. These materials also composed part of the evidence for a lawsuit Dietrich filed in his home county in Michigan, which a judge threw out on the grounds that it dealt with activities outside the state.

“This man becoming president wants to buy a resort within the same week he became president,” Dietrich told The Daily Beast. “He wanted 51 percent, but he didn’t want to pay the value of 51 percent.”

The Haitian law firm involved in the correspondence Dietrich shared, Cabinet Lissade, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. The office employs multiple attorneys who have worked for President Martelly and Prime Minister Lamothe, and for the Haitian government.

Dietrich also shared what he described as counter-offers he sent back to Martelly’s interlocutors as negotiations to build out Abaka Bay continued. In his open letter, and in conversations with The Daily Beast and other publications, and in the court case lodged in Michigan, he accused his ex in-laws of subsequently pushing him out of the business entirely.

But the project forged ahead. To realize the vision of a grand resort, in 2013 Martelly decreed the entire 20 square miles of Ile-à-Vache a public utility, effectively dispossessing the native population, who had informally passed down homes and property for generations.

A Montreal-based urban planner named Olthene Tanisma, a native of Haiti, told The Daily Beast he was recruited through family connections to draw up designs for the resort. He has since sued the Haitian government in a Canadian court, claiming it failed to compensate him for his work. In an interview, he recalled the island’s beauty and hospitality, as well as its rudimentary physical and civic infrastructure.

“This is one of the best pieces of beach I have ever seen in Haiti,” Tanisma recollected. “They have good food, and no organization.”

It was the same way that activist Nixon Boumba found it when he first visited in 2012—and when he returned a year later to rally opposition to the project.

“Ile-à-Vache was very rural, very rustic, very exotic,” he recalled. “People move on this island on foot, use a cow sometimes, but they move from one part to another part by walking.”

It was the start of construction that finally fired local ire, as the first work on a planned airfield and a cross-island road erased homes, gardens, and fruit tree groves. The local farmers organized into the Konbit Peyizan Ile-à-Vache, or Ile-à-Vache Peasants Collective, and sought to block the development with demonstrations. Boumba and other Haitian sources recalled clashes with police, as well as opposition leaders jailed or compelled to flee.

By the time President Martelly left office in 2016, the project had stalled, thanks both to the local friction and to corrosive corruption on a national scale: the billions in foreign aid intended to rejuvenate Haiti after the earthquake had simply vanished without results—including the PetroCaribe money earmarked for tourism ventures.

Canada sanctioned Martelly in 2022 for facilitating “the illegal activities of armed criminal gangs, including through money laundering and other acts of corruption.” Last year, the U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken barred former Prime Minister Lamothe from entering the country, accusing the politician of having “misappropriated at least $60 million from the Haitian government’s PetroCaribe infrastructure investment and social welfare fund for private gain.” A Haitian judge issued arrest warrants for both men in January on charges of “complicity in corruption and influence-peddling linked to the misappropriation of public property.”

For Tanisma, the planner, the debacle on Ile-à-Vache was just one facet of a vast, squandered opportunity.

“There was money, for the first time in Haiti—there was money to do what they wanted,” he lamented. “That’s what bothers me, as a Haitian.”

It was into this context that Ballard, Lopez, and their O.U.R. confreres parachuted last decade. Operation Toussaint, the 2018 documentary, leaves the impression that donations to O.U.R. would enable additional missions to find Gardy Mardy—and in the process to save other missing children from traffickers.

“The more we go looking for Gardy, a funny thing happens, every time we go looking for him, we find other kids,” Ballard asserts in the picture.

But the glossy film covered a sordid reality, as Lopez would reveal to a Utah prosecutor’s office in 2020. Far from the scenes of body armor-clad U.S. vets rolling through Port-au-Prince streets to strike child brothels, Lopez reported the number of raids the group actually participated in was so low as to be “staggering.”

“If people knew that they actually weren’t the ones doing the operations, they would feel incredibly deceived,” an investigator from the Davis County attorney’s office wrote in his notes from the conversation with the ex-SEAL.

As Vice first reported last year, Lopez further disclosed that the group provided just occasional consulting and equipment to local law enforcement, then took credit for their anti-trafficking actions. He also claimed that “the only form of intelligence” O.U.R. had used in its quest to locate Gardy Mardy were readings from a Utah-based psychic.

This is consistent with what The Daily Beast heard from Haitian sources, who believed O.U.R. was mainly an apparatus for milking cash from supporters in the United States.

But if Operation Toussaint was misleading in one sense, it was revealing in another: it showcased the group’s links with Haitian government figures, namely with top Port-au-Prince prosecutor Clame Ocnam Dameus, his chief-of-staff Jim Petiote, and Petiote’s wife Sabine Martelly, a relative and political ally of President Martelly who held a post in his administration. All three Haitian officials appear in the picture at a press conference and a stage-managed sitdown with Utah Attorney General Reyes, while Petiote appears in a training scene with Lopez.

When Petiote died in January 2019, Ballard eulogized him on Facebook as the group’s “lead operator in Haiti.” Meanwhile, Sabine Martelly identified herself online as O.U.R.’s “representative in Haiti,” and described the American organization as a “partner” and financial supporter of her personal nonprofit. Her nonprofit’s website features a prominent photo of her with Lopez, and an older iteration of the page describes him as “our number #1 [sic] supporter.”

Sabine Martelly’s social media also shows she and her husband traveled to Utah in 2018 for Operation Toussaint’s premiere—again taking time to pose with Lopez. She declined to comment for this story.

A view of a hotel in Ile-à-Vache, a paradise island in Les Cayes.

Clement Sabourin/Getty ImagesAccording to Vice and others, the fissure opened between Ballard and Lopez after an August 2019 meeting in which the O.U.R. founder laid out a plan to divert the “sizzle” from the child rescue operation into various for-profit ventures. The organization has maintained that what Lopez described as a betrayal of its mission and donors was in fact a plan to transition from a frontline to a facilitating role in combating the illicit sex trade.

“Mr. Lopez’s criticisms are based on a misinterpretation of Mr. Ballard’s comments about fundraising and a fundamental misunderstanding of O.U.R.’s strategic decision to gradually shift its operations from O.U.R. operators conducting the missions, to a more collaborative model where O.U.R. would educate, assist and support local authorities in conducting rescues,” a spokesperson for the group told The Daily Beast. “The hope is that eventually an organization like O.U.R. is unnecessary and that governments, police forces and agencies have the training and resources themselves to stop human trafficking on their own."

And 2019 had already held plenty of sizzle for Lopez himself—and for Sabine Martelly, The Daily Beast can report. And sources with knowledge of the situation said it was Lopez’s pursuit of a hot opportunity on Ile-à-Vache that cauterized his ties with O.U.R.

The Daily Beast viewed a copy of a letter of intent signed that February between the Haitian state and Watersmark S.A., a company that Lopez’s LinkedIn shows he co-founded one month prior. The plan was if anything even grander than the unrealized outline from a few years before, including not just an airport and road, but a tourist hospital, condos, a conference center, a golf course, a tennis stadium, an equestrian center, a polo range, a Caribbean cultural center, a culinary school with dormitory facilities, a cruise ship terminal—and “a new village for the relocation of local residents.”

The arrangement called for completion within 39 months. It also asserted that Watersmark S.A. already possessed $2.5 billion in financing. No one has alleged this deal violated either Haitian or American law, but materials The Daily Beast reviewed raise questions as to why Port-au-Prince decided to work with Lopez and his partners, and about the project’s viability.

The accord came after Haiti and the U.S. had both undergone a change in administration. In 2016, President Martelly successfully handed the Caribbean nation’s reins to his handpicked candidate, Jovenel Moise, who maintained the government’s relationship with O.U.R. Meanwhile, despite campaign trail attacks on the Clinton State Department, Clinton family, and Clinton Foundation’s involvement in the disastrous Haitian recovery effort, Trump hardly modified American policy toward the country once in office, according to Dr. Fatton. But now, O.U.R. had allies not just in the State of Utah but at the apex of American power.

In a podcast interview in Jan. 2020, Lopez described his work for Blackwater’s Erik Prince—the brother of Trump Education Secretary Betsy Devos—in the present tense, touting the mercenary’s controversial proposal to effectively privatize the U.S. role in Afghanistan. Prince had developed this plan at the behest of Steve Bannon and Jared Kushner, and repeatedly and publicly pressed it upon the White House despite Pentagon opposition.

Lopez also stated that Watersmark had inked a lease agreement with the Haitian government for the Ile-a-Vache project. And he was not shy about acknowledging his connections through O.U.R. had helped forge the deal.

“A lot of the work I did in Haiti helped me to have relationships within the government down there,” he told host Jimmy Rex. “I kind of helped bring the right kind of partners and teams down that wanted to implement a strategy that could develop that island into a multi-billion dollar resort with a new airport, new cruise ship terminal, in the south of the country, that was gonna basically create a massive stimulus program for the government of Haiti, who is a partner in this project.”

Lopez did not name his contacts or his business associates, but broadly alluded to what he claimed was a highly favorable environment on the U.S. side—even as he acknowledged the fraught situation in Haiti, where Moise had begun ruling by decree amid massive protests over his own role in the PetroCaribe embezzlement scandal.

“The president of Haiti has been—the politics have been pretty tense down in Haiti for the last year or so,” Lopez said. “We are pushing forward heavily, and we happened to time things at a very good moment where different entities in the US are looking to invest directly into Haitian infrastructure that’s a US backed construction project.”

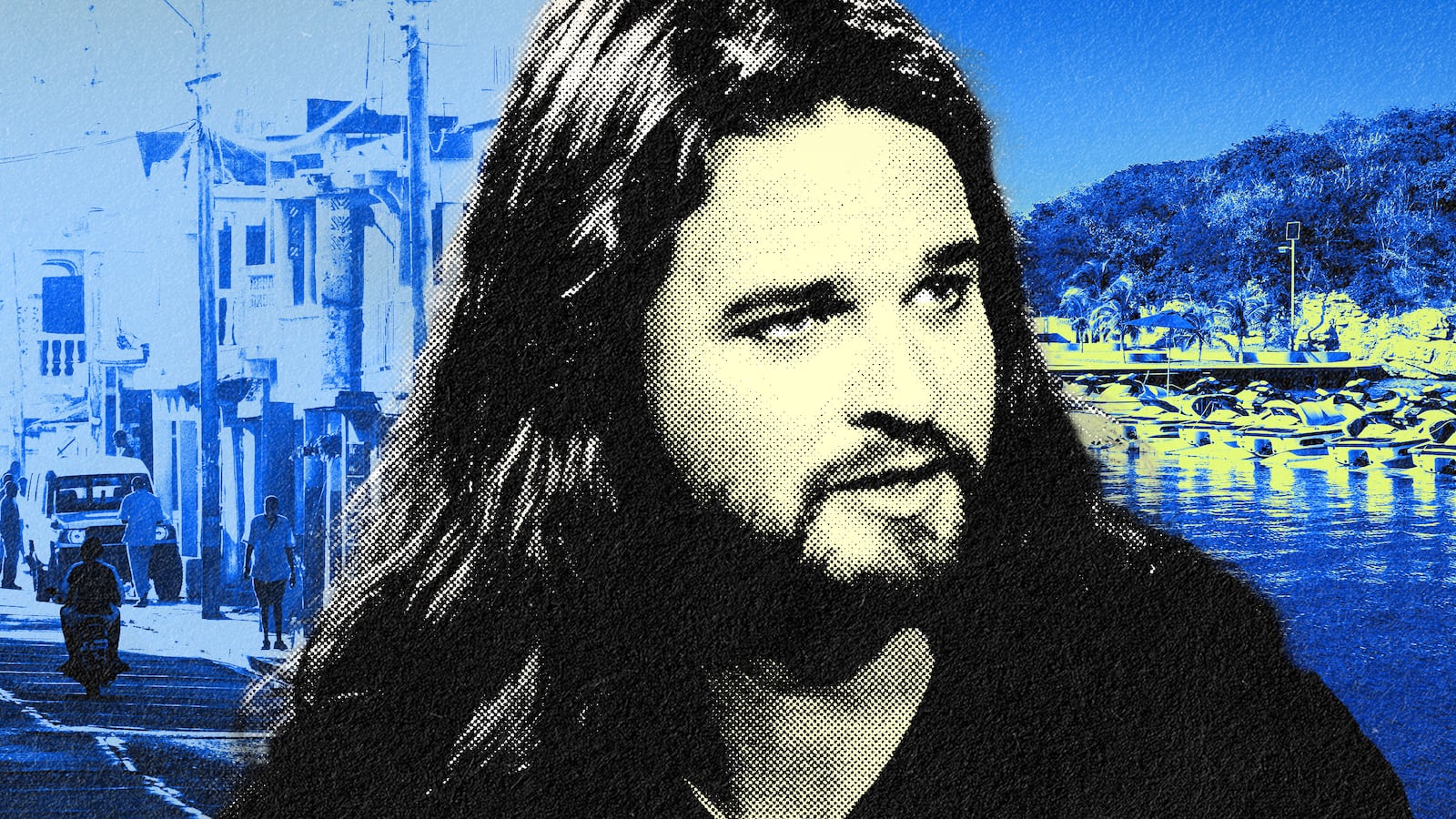

Dave Lopez.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/YouTubeLopez insisted, however, the Ile-à-Vache project was clean, and even claimed to have “seen politicians completely turn away massive bribes that they were offered in order to do business the right way for this project to get started.” He also maintained that the development would advance the goals for which he had ostensibly traveled to Haiti in the first place.

And even though the interview occurred only months after his purported disillusionment with Ballard, and only months before he began cooperating with investigators, Lopez praised the O.U.R. founder.

“We can have a great capacity to do good, and to affect, even for the anti-trafficking missions there in Haiti. It gives us tremendous capacity,” Lopez said, speaking of the Ile-à-Vache project.

“Tim Ballard started that organization, and I’ll forever be indebted to him for his work he did to pioneer this issue.”

Ballard, for his part, denied any involvement in the resort-building venture.

“Tim’s focus throughout multiple anti-trafficking missions to Haiti was doing everything possible to help rescue women and children from sexual slavery,” spokesman Chad Kolton told The Daily Beast. “He never spoke to any government officials about development projects.”

Public records and documents The Daily Beast reviewed reveal who Lopez’s partners were. An entity called Watersmark Inc. formed in Utah just a month before the aspiring entrepreneur ratted out Ballard. One of its directors was Lopez, another Fernand Sajous, Dietrich’s ex-father-in-law and owner of the Abaka Bay hotel. Sajous did not respond to multiple queries from The Daily Beast.

A third was a Utah- and Florida-based businessman named Brent Woodson, the only one with any apparent experience developing—or at least, proposing—projects of scale. Woodson has operated under the Watersmark brand with a rotating cast of partners of varying political bents and affiliations since at least 2005, corporate records show. The Daily Beast sought to reach Woodson via email, phone, text message, and through family, but received no reply.

Despite Lopez’s claims to have assembled the team behind the project, archived versions of Watersmark’s website show it has included a page on Ile-à-Vache since at least March 2016: that is, around the time the original vision for the island faded. These pages only ceased to be password-protected after April 2019, following the letter of intent agreement.

It was Woodson, insiders told The Daily Beast, who presented himself in Port-au-Prince as the consortium’s money manager. Woodson has long claimed to have worked for members of the Saudi royal family, and Haitian sources said he boasted of relations with the Al Maktoum family that rules Dubai.

But the only direct connection between Woodson and the Persian Gulf that The Daily Beast could substantiate came from a Utah Department of Commerce investigator’s affidavit in 2006, which found he had received money for an odd Middle Eastern investment from a pair of securities fraudsters. Woodson pleaded ignorance of the funds’ origin, and was not charged in the case.

“The remaining $75,000 was for an investment in uncut diamonds with a Mr. Brent Woodson, who in turn invested with a man named Abdul (?) in Saudi Arabia,” the investigator wrote. “The diamond investment has not paid off.”

That would not be the last time Woodson would allegedly wind up with cash of dubious provenance. In 2011, the court-appointed trustee managing the ill-gotten assets of a $167 million Ponzi scheme deemed “the second-largest financial fraud in Utah history” filed a complaint alleging Woodson had illicitly received $31,000 from the scam company. The trustee dropped the proceeding after they could not locate Woodson to serve him papers.

The Daily Beast also uncovered a previous Woodson venture that sought to raise cash from Chinese investors to construct a stadium complex in the Dominican Republic, and another Utah company launched in 2021 that claims to obtain clients second passports from the tiny Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda in exchange for down payments on development projects there.

Sources informed The Daily Beast that Woodson had access to funding from a California-based beauty product company and a storage facility builder operating on the East and West Coasts. The Daily Beast also found web videos from a campaign called “Light Up Haiti,” that urged Americans to buy the hand-cranked “Watersmark Survival Generator” for Haitians who wanted to charge their phones.

It seems unlikely any of these efforts would have produced $2.5 billion, and whether or how Watersmark came into that funding remains unclear. But a document showing projected payroll for the Ile-à-Vache project The Daily Beast reviewed gives an idea how the company intended to spend it.

This undated plan shows that Woodson, Abaka Bay owner Sajous, Lopez, and another longtime Woodson associate would each earn around $25,000 a month for at least the first half-year of the development’s duration. It also shows that the entrepreneurs sought to bring aboard an individual with the same name as one of the fraudsters who had invested in Woodson’s uncut diamond endeavor, as well as an attorney from the Haitian firm Cabinet Lissade. This is the same firm whose name appears on the documents Robert Dietrich, the scorned Abaka Bay co-owner, sent to The Daily Beast as evidence of business proposals from President Martelly. Salim Succar, a lawyer who served as President Martelly’s deputy chief-of-staff and Prime Minister Lamothe’s top aide and legal counsel, is a partner at the firm.

A fisherman mends his net in Ile-à-Vache, Haiti on July 19, 2015.

Keith Bedford/The Boston Globe via Getty ImagesAlso on this payment document is Sabine Martelly, whom it slated to receive a comparative pittance of $2,000 a month. But this appears not to be her only interest in the project. In April 2021, she became manager, along with Woodson and Lopez, of a new for-profit Florida company called Watersmark Works LLC. The exact function of this company is unclear, but the following year she incorporated another entity in the Sunshine State, SabSMart Logistics.

None of this shocked UVA’s Fatton.

“This is very business as usual for those kinds of enterprises in Haiti. Those things are done in very strange ways—personal associations of Haitian figures, politicians, businessmen,” the professor told The Daily Beast. “I wouldn’t be surprised if all those bizarre links would crystallize in Ile-à-Vache.”

But Boumba, the activist who organized against the first version of the Ile-à-Vache project, reported little progress in actual construction on the island since Lopez and his associates closed the deal—which sources closer to Port-au-Prince confirmed. And this owes to both national and international factors.

First came the COVID-19 pandemic, which found Lopez sheltering in place at Abaka Bay.

“Wouldn’t you like to be locked down here?” he wrote on LinkedIn in the first months of the public health catastrophe, sharing a photo of boats coasting on Ile-à-Vache’s turquoise surf, a picture that serves as his account’s banner image even today.

“The Island nobody's heard of… yet,” he wrote a year later, captioning a shot of lathered sand and a dock at sunset.

The placid visuals contrast with the chaos that would soon wrack the nation. In July 2021, a band of Colombian mercenaries assassinated President Moise. Haiti soon spiraled into gang-harried anarchy.

It is this humanitarian disaster, coupled with the interim government’s struggles to assert legitimacy and control, that has forestalled the Ile-à-Vache initiative for now, The Daily Beast’s contacts said.

But elections loom in both Haiti and the U.S., with Trump and Martelly each eyeing a return to power, despite their respective legal challenges. A comeback by either could revive the project’s fortunes, according to sources, as Woodson and Lopez reportedly boasted often of their influence within the former American president’s administration. And so the future of Ile-à-Vache and its people remains as uncertain as it was a decade ago.