Eighty years ago, before Fifty Shades of Grey was even a twinkle in E.L. James’s eye, librarians across the country were asked how they might respond to another controversial book if it became available in a reasonably priced edition. The book in question? James Joyce’s Ulysses.

No one would argue that, from a literary perspective, Fifty Shades of Grey is the next Ulysses. And yet the terms of the debate surrounding the acceptability of James’s novel on library shelves are not that far from those recorded in a series of questionnaires sent to public and university libraries by Random House in preparation for a federal Ulysses obscenity trial. (Random House is also the publisher for Fifty Shades of Grey and is fighting bans in Georgia and Wisconsin.) At issue: whether the book had any literary merit and if a library had any business with such a controversial book on its shelf. Sound familiar? (The American Library Association recently issued a statement encouraging librarians to keep in mind their “core values of intellectual freedom and providing access to information.”)

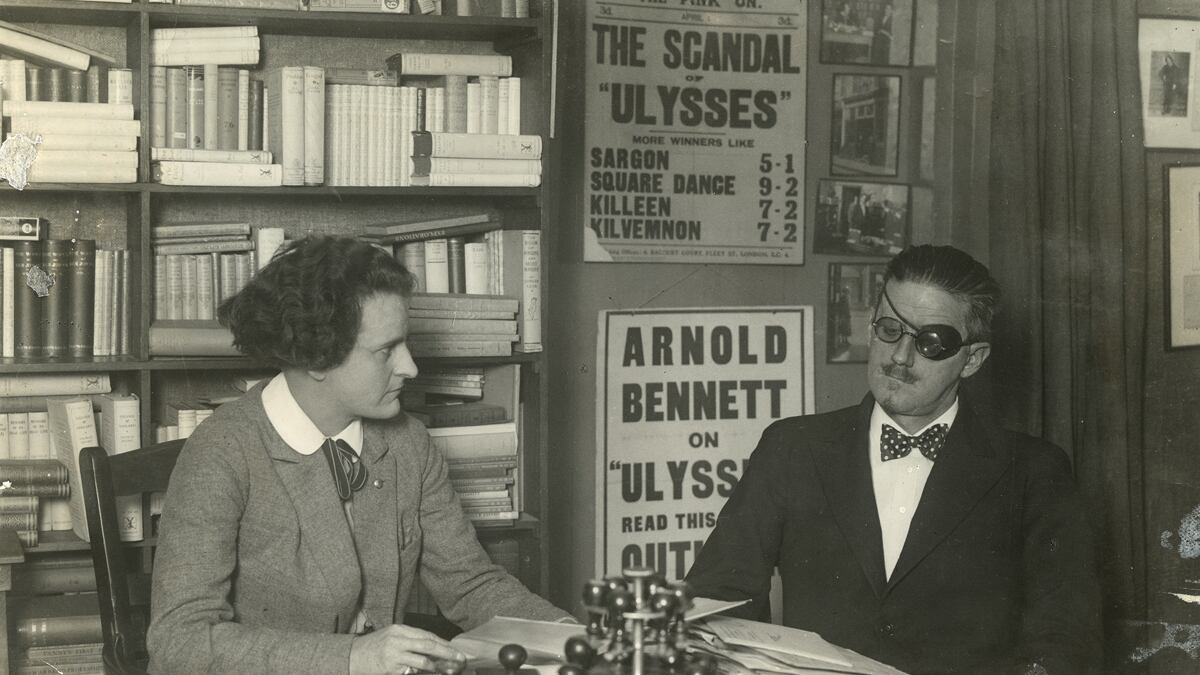

The Ulysses library questionnaires are preserved at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center (where I work as a curator), in the archive of famed anti-censorship attorney Morris L. Ernst, who successfully led the defense of Joyce’s novel. Today they provide a fascinating look at public and professional opinion of Ulysses before it was an established classic.

The surveyed librarians weighed in with a wide range of opinions of the novel: a “psychological extravaganza rather than a work of fictional art,” “literary ‘jazz,’ intriguing for sophisticated half-morons,” “well-nigh unreadable in its entirety,” and “decidedly overrated.” Though he had not read Ulysses, Gilbert H. Doane of the University of Nebraska Library questioned its “value as literature” on the basis that he had “never been convinced that Mr. Joyce knows how to write in English.” Louis Shores at Fisk University was among the relatively few librarians who offered an unequivocal statement of Ulysses’s importance to literary history as “an essential text we feel handicapped at not being able to supply.” Edward Bergin, librarian at the University of Detroit, did not complete the survey but wrote in at the bottom, “I, for one, wish to raise a voice in the name of decency to deprecate the marketing of filth,” making his counter-assessment of Ulysses quite clear.

At Ernst’s behest, Random House mailed questionnaires across the country, in major cities and small towns. Ernst even sought to find out how Ulysses might play in Peoria (not well, if the returned survey is any indication). There are some predictable responses from smaller communities, including one from a librarian in Clarksburg, W.V., clearly unfamiliar with Joyce’s work, who explained, “Homer is not much read except by students as ‘required reading.’” Collectively, though, the responses challenge geographical assumptions about the Midwest, the South, small towns, and small-mindedness. Alberta Caille, the librarian at Carnegie Free Public Library in Sioux Falls, S.D., believed that the novel had literary value and was “rather outstanding in its psychological contribution.” Her peers in Omaha, Neb., and Amarillo, Texas, concurred. Ethel McNeely of the North Dakota Agricultural College argued that the “[b]ook deserves unrestricted circulation as a contribution to literature.” Others agreed with Bella Steuernagel of the Belleville (Illinois) Public Library who felt “very emphatically, that [Ulysses] has no place in a public library.”

Many librarians, both public and university, believed that only readers of a certain type could extract the appropriate meaning from it and that most interest in Ulysses was prurient. The librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library turned to its copy of the book to prove her point, it “is practically in tact except the last hundred pages which are very badly worn.” Given this concern about “proper” reading, many librarians advocated restricting circulation. Duke University’s librarian believed that his library “ought to have a copy, but that the copy should be kept on locked shelves and its circulation supervised.” The librarian in Pottsville, Pa., lamented her role as “gate-keeper,” noting “that I get mortally weary of keeping the clever from being rude to the good and I wish that booksellers would continue to be the fellows that have to chaperone Ulysses.” Theodore W. Koch at Northwestern University kept his copy locked in his desk, noting he doubted “whether [the] administration would approve of its being made available.”

Librarians in 1932 were just as aware of their constituencies and boards as those attempting to address the Fifty Shades of Grey controversy today. The librarian at the Riverside Public Library (California), who reported interest from “army officers and men of leisure,” believed that “our book committee would refuse to purchase because of the reputation of the book.” And at the State Teachers College in Warrensburg, Mo., the librarian noted, “We have many old women of both sexes in our town who are always ready to find fault with our books.” In a statement that sounds as if it might have been written yesterday, the chief librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library summarized his plight this way, “You are aware, of course, of the difficulties encountered by public libraries which attempt to stock something out of the ordinary. The readers who are often best able to judge have a habit of saying nothing, while others may be very much more outspoken in condemnation both of the book and of the library.”

Ulysses was, of course, finally cleared of federal obscenity charges, and 80 years later is hailed as a literary classic. Not long ago, the Brevard County Public Library system had rejected carrying Fifty Shades of Grey, which it viewed as “pornographic material.” It has since reversed the ban, and the book now resides comfortably on the shelves of the branch libraries—the erotica of E.L. James alongside the works of James Joyce.