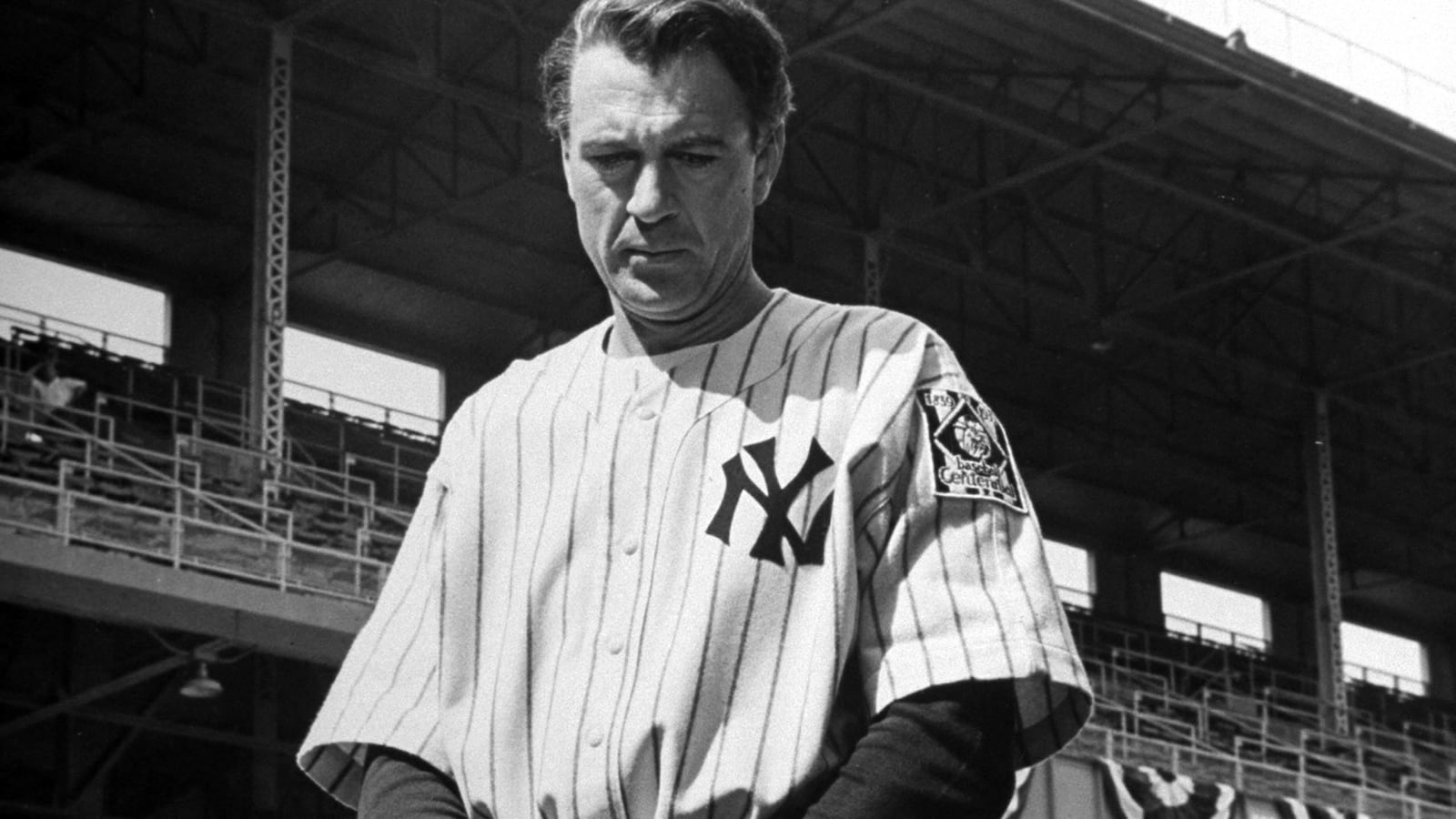

Gary Cooper’s performance as Lou Gehrig in The Pride of the Yankees is so indelible that envisioning anyone else in the role is impossible. Had Cooper not played Gehrig, The Pride of the Yankees might not have been made or, if producer Sam Goldwyn had signed another actor, like Eddie Albert, Pride would have been a different and probably forgettable picture. Cooper’s portrayal was as critical to the timelessness of Pride as Clark Gable’s was to Gone with the Wind and Humphrey Bogart’s was to Casablanca.

Still, there were other candidates to play Gehrig—or at least names raised to pique the interest of the public. Despite expressing thoughts early on about Cooper and Spencer Tracy in the role of her husband, Eleanor soon after kept her preferences to herself at a luncheon with reporters to celebrate her deal with Goldwyn.

“I have four or five different stars in mind but I do not wish to name them because I have confidence that Mr. Goldwyn will see to it that the film is properly cast,” she told reporters at Perino’s, a Los Angeles hangout for Frank Sinatra, Bette Davis, and Cole Porter. “I believe he is the man most capable of bringing the real picture of Lou to the screen.”

Already, she was playing the publicity game.

Goldwyn, meanwhile, had begun soliciting the views of thousands of sportswriters. He also asked fans to write the studio, where his publicist claimed that the request was generating 1,100 letters a week. And he lined up a group of marketing allies—publications as diverse as the Sporting News and Cosmopolitan magazine, and the prestigious Gallup polling organization—that produced myriad names for the lead in Pride in addition to Cooper, the obvious one. Cooper, by then, was being seen in theaters in Sergeant York, a film about a real-life backwoods Tennessee hero during World War I that would bring him his first Academy Award.

As he began his casting quest, Goldwyn issued a statement that spoke to the absurdity of his marketing song-and-dance with a bold suggestion that science, not the typical Hollywood commerce he trafficked in, led him to produce Pride.

“The results of a Hollywood poll made confidentially by Gallup’s American Institute of Public Opinion were made public today by Samuel Goldwyn, who announced that he was largely motivated to make his production of the life of Lou Gehrig by the findings of the survey,” his studio announced.

The message: forget the newsreels of Gehrig’s “luckiest man “speech on July 4, 1939 that Niven Busch, one of Goldwyn’s story editors, had shown him and made him weep and demand that Eleanor Gehrig be called.

Now Goldwyn could publicly say: I’ve market-tested my baseball biopic—and it is precisely about the man and the sport America wants to see.

The results of Gallup’s survey of theatergoers, released in early October 1941, found that of seven professions they would like to see portrayed on the silver screen—surprise!—they wanted to see a big-league baseball player.

And of all the candidates whose stories they wanted to see on the screen they most wanted it to be Gehrig.

Cooper led the list of actors surveyed by Gallup, followed by Eddie Albert, Pat O’Brien, Cary Grant, Fred McMurray, Spencer Tracy, William Gargan, Brian Donlevy and Big Boy Williams, who known as the Babe Ruth of polo.

Meanwhile, Walsh was having a grand time working as a publicist for Goldwyn. In early October, he sent a note to reporters covering the World Series between the Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers that exclaimed: “WHO IS GOING TO PLAY THE ROLE OF LOU GEHRIG?” He added: “In the interests of good reporting, let me say that Mr. Goldwyn has not and will not decide on the actor for some time to come. It may be Spencer Tracy, or Gary Cooper, or it may be a `dark horse.’ It is not impossible that one of several professional ball players might get the part.”

This was pure hokum, of course, lavished on a captive group of reporters focused on the Yankees and Dodgers playing in their first Subway Series.

Walsh all but confessed that he was helping Goldwyn pull off a ruse.

“That silly contest as to who ain’t gonna play Lou still gets a lot of space,” he wrote to Eleanor. “You knew there was a row between the studio and Louella when she flatly announced Coop had the role about a month back.” Parsons had written that “There is every reason why he should have the part, for he is under contract to Sam and he is Mrs. Gehrig’s choice.”

Eleanor was moving closer to endorsing Cooper for reasons that would please Goldwyn. An independent producer, Goldwyn was a Polish immigrant who rose from glovemaker in upstate New York to great independent producer. He knew nothing about baseball—indeed, he thought baseball was “box office poison—and ordained that Pride be the story of a humble, courageous hero (Gehrig) and the love he felt for Eleanor. She knew that Cooper was nearly as unfamiliar with baseball, and would not be able to mimic Lou’s extraordinary skills.

“Why does it matter that he isn’t the ballplayer Lou was?” she told the syndicated columnist Bob Considine. “Who is? The important thing is to capture the spirit of Lou and I don’t know anyone else who would do it as well.”

The Sporting News, the St. Louis-based bible of baseball, was central to Goldwyn’s casting folderol. The weekly newspaper’s authority in the baseball industry conferred credibility on Goldwyn, who would have been flummoxed by its pages of box scores and its insider’s take on baseball. But it was the perfect cheerleader for the film and the ideal clearinghouse for fans voting on an issue that could stir passions in the few months before the United States entered World War II.

In all, 44 men were nominated by the newspaper’s readers—23 actors and 21 ballplayers—but Goldwyn was not going to hire a ballplayer to play Gehrig. It was too gimmicky for Goldwyn’s bigger ambitions. Cooper was among the Sporting News’ list of actors, with John Wayne, Lew Ayres, Ronald Reagan, Big Boy Williams, Lionel Barrymore (at 63, he was older than Elsa Janssen, who was cast to play Mom Gehrig), and George Tobias, who in the ’60s would portray Abner Kravitz, husband to Gladys Kravitz on Bewitched, the sitcom starring Elizabeth Montgomery as a witch who did as she pleased by wiggling her nose.

Today it seems nearly absurd to think that Eddie Albert might have played Gehrig. Over a long career his best-known role was Oliver Wendell Douglas, the white-haired city lawyer in Green Acres, the rural ’60s comedy, who leaves his Manhattan practice for farm living where he finds himself surrounded by hicks, oddballs, and Arnold Ziffel, the celebrated thespian pig of Hooterville.

But in 1941, Albert was a handsome singer and actor, who had appeared on radio and in films. And he had clearly impressed one well-known baseball man: Ed Barrow, the Yankees’ longtime president and dynasty builder. Hedda Hopper, Parsons’s great gossip rival, wrote that Barrow was leading the Albert campaign. Barrow himself wrote in early August that “he is the actor who reminds me most of Lou. He has Lou’s dimples he doesn’t have his build but he looks like a southpaw.”

Later that month, he reiterated his support for Albert to the actor’s manager but retreated from any further role in his advocacy for Albert.

“In fact,” he wrote, “I have already been accused of sticking my nose into something I know nothing about.”

* * *

By early December, Goldwyn still had not announced his decision.

And the Sporting News was still doing his bidding.

Spread across one of its broadsheet pages were photos of five men: Gehrig, Cooper, Albert, Chicago White Sox pitcher Johnny Humphries, and longtime major-league pitcher Al Hollingsworth, who spent the 1941 season in the minors and had a 21-9 record. Still, Goldwyn was in the habit of making big movies with major stars and one cannot image a theater marquee saying: The Pride of the Yankees, starring Johnny Humphries.

Based only on physical resemblance to Gehrig, many readers had voted for Albert, among the actors, even though it is difficult to agree with what they were looking at. One reader said that Albert would be even better if he were built like the handsome actor George O’Brien, a heavyweight boxing champion of the Pacific Fleet during World War I whose credits included, coincidentally, a 1924 silent film called The Iron Horse. Cooper finished first in the voting among the actors, his reputation as one of Hollywood’s biggest actors known for playing character of quiet dignity no doubt having a significant effect.

Among the ballplayers, the most votes for their fidelity to Gehrig’s looks went to Humphries, with his dimpled chin, and Hollingsworth. The remaining candidates included some odd choices that suggested readers were willy-nilly tossing ballplayers and actors into the hopper, from Eddie Duberstein (a career minor-leaguer) to Ted North (billed fourth in the film Charlie Chan in Rio) to Milt Galatzer (whose modest results in a few years in the majors did not distinguish him). Babe Ruth—whose looks were sui generis—received some votes, as did Wally Pipp and Babe Dahlgren (Gehrig’s predecessor and successor at first base). Lon Chaney Jr. was nominated but he never got any closer to Gehrig than when he appeared with Cooper in High Noon in 1952.

The women’s vote coming from readers of Cosmopolitan gave Cooper a resounding victory, with 4,354 votes to Albert’s 2,132 and Reagan’s 1,025.

Goldwyn waited nearly until the end of the year to announced his decision, delaying it for a week after naming Sam Wood to direct Pride. Sports editors got the word about Cooper when Walsh sent personalized telegrams on Christmas Eve

In a wire to the Montana Standard’s sports editor, he wrote: “Here’s something to put in your sports page Christmas stocking. Samuel Goldwyn formally announced today Gary Cooper will play lead in Lou Gehrig picture. Mr. Goldwyn’s final decision, based on six months’ sampling of public opinion with Gehrig leading polls conducted by Cosmopolitan magazine, Movie and Radio Guide, the Sporting News, and consulting more than 1,000 newspaper sports writers. As you voted for Cooper, please accept my congratulations on your ability as a casting expert.”

There was little doubt that Cooper could play Gehrig. He was one of the leading actors of his day, the star of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Beau Geste, The Westerner, Meet John Doe, Sergeant York, and Ball of Fire. But years later, he said he was worried—not so much about learning to play baseball—but about portraying a beloved and admired personality who had so recently died.

“Gehrig, that’s no cinch,” he told the Saturday Evening Post in 1956. “Quite a responsibility, in fact, when you think of all those millions of people who knew him, watched him, knew just how he handled himself. You can’t trick up a character like that with mannerisms, bits of business. I honestly didn’t want to take the part but Mrs. Gehrig came out and she told me that’s the way she wanted it.”

The author of The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper and the Making of a Classic, Richard Sandomir has been the award-winning sports media and sports business writer for the New York Times since 1991. He is the author or co-author of several books, including Bald Like Me, and, most recently, The Enlightened Bracketologist, and its sequel, The Final Four of Everything.