Leaning against the rail, gazing into the dirt arena, I felt like an interloper. Everyone around me knew what was going on. Spectators dressed in matching cowboy boots, hats, plaid shirts, and jeans fastened with swanky belt buckles could have been in costume, except most of the boots were scuffed and the shirts were worn soft. Meanwhile they all cheered as if on cue to commentary that included mystifying terms like “flanking” and “pigging string.”

Suddenly there was action. A calf was released from the chute for roping, and in a cloud of dust a cowboy on horseback galloped after him, rope in hand. A plea of “Go little cow!” sprang unbidden from my lips and I cringed as the calf was roped, flipped to the ground, and tied up by the cowboy—achieving a time that set the crowd roaring.

Uneasy, I reminded myself I was here on a mission and hating on a mean-to-a-little-cow cowboy wasn’t best way to start. I was here to understand the rodeo and though my guide was a bit unorthodox (I’ll get to that) I felt I owed it to him to stay open-minded.

My visit to the Calgary Stampede didn’t start the normal way—on the midway, scarfing down giant squid on a stick, corndog poutine, or pickle ice cream before hopping on a stomach-churning ride. Instead it began outside a heritage home on the streets of Montreal. A journey has to start somewhere, and I found myself far from my western Canadian home of Vancouver, hunting down a piece of family folklore. The story involved a pair of my ancestors: Montreal’s aristocratic Cross brothers, Harry and Ernest.

Thanks to Harry’s love of journaling, I’d been tracking them for a while—from the time their (and my) ancestors fled Scotland for Lower Canada (apparently to escape an English rule that forbade the conquered Scots from wearing kilts) to Harry’s birth in 1854 and the younger Ernest’s arrival in 1861. From Harry’s journals I followed him and his siblings through the streets of a nascent Montreal in their Victoria coach (drawn by a pair of gaited Morgans) and on through an elite education at the High School of Montreal and the Upper Canada College in Toronto.

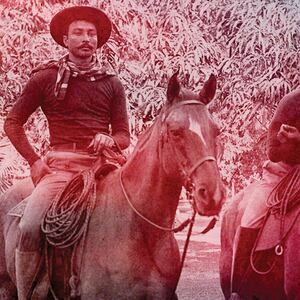

Then, just as the two seemed destined to settle into a privileged life of banking, lawyering, and running our fledgling country, Harry reported in his journal that a friend and “scoundrel” had come through town and plans had changed. "We were seduced by the wild and wooly romantic land of big open spaces; a rendezvous for Indians, buffalos, pioneers, cowboys, mountain men, miners and cattle." Harry decided that it was, "far more exciting to think of making my fortune as a cattleman than either a banker or lawyer."

In other words—the boys (as I’d come to think of them) had decided to head West.

This could have been the end of the story for Harry and Ernest. A lot of young men died trying to make their fortune as cowboys (including the friend who tempted them West). But instead, a distant cousin hinted at an unexpected outcome. He told me they both became famous cowboys; Harry went to Wyoming and Ernest had a role in founding the Calgary Stampede.

With possible fame as a clue, it didn’t take long to discern that Ernest had become AE Cross. Wikipedia told me he moved to Alberta in 1884 to work at a ranch and by 1886 he’d founded his own A7 Ranche, located near Nanton, Alberta. Not long after, he established the Calgary Brewing and Malting Company, the region’s first brewery.

I was liking my ancestor more and more.

AE seemed to love all things cowboy and in 1886, while recovering from a bronco-busting injury, he moved to Calgary and helped organize the city’s first agricultural fair. Back then Cowtown, as Calgary affectionately came to be nicknamed, was home to about 1,000 people and had little more to offer than a police post and train station. But it was cowboy country as far as Canada was concerned, and the fair was an opportunity to share knowledge and showcase the best of the West. Meanwhile, around the same time, Wild West shows were becoming a big deal in the U.S., featuring huge casts of sharpshooters, trick riders, and ropers. The romantic mystique of the West was a hot commodity.

The Calgary Stampede was born out of these two ideas: sharing both the reality and the romance of a way of life. Rather ironically, the first stampede was meant to be the last. The four men who put up the money for the show (they make up what’s now called the Big Four and include Cross) saw it as a one-time party, a farewell to a dying way of life. The West had been won and Canada’s frontier had been settled.

I thought of this as I wandered through the hay-scented barns with a modern cowboy (I’m pretty sure the ghost of AE was right beside me). From him (the modern cowboy, not the ghost) I learned about the breeds of horses, how they were raised, and how each rodeo event worked. Even though AE thought the time of the cowboy had ended over 100 years ago, as I watched my modern cowboy whisper soft words in his horse’s ear, while defending the sport of rodeo, it was clear the lifestyle was still going strong.

In AE’s time the parade and agricultural showing of livestock was the big deal at the Stampede. The rodeo part of things was more informal. The disorganized cowboy races didn’t have many rules other than the participants needed to wear a “full cowboy costume.” And like today, there was also controversy. A notorious “bucking contest” at the time brought out the wrath of one journalist who claimed, “Those responsible for the ‘show’ should be hauled up for cruelty to animals.”

As the Stampede has continued, animal care has improved dramatically and those involved explain most of the events are tied to the history of ranch life in some way. Tie-down roping is a show of immobilizing the calf as quickly and safely as possible to give it medical treatment. Saddle bronc riding (bucking bronco) evolved out of breaking and training horses and includes a whole host of technical skills. Bull riding has much more gruesome roots; evolving as a rodeo alternative to bullfighting, where the bulls were literally ridden to death.

Today the health and well-being of the animals and riders is paramount—but accidents do happen.

Back out at the arena, the rodeo was in full swing. Athletic riders cautiously mounted unbroken horses and then set off one after another, each hoping to stay on their bucking horses for at least eight seconds. Now, as the crowd in the stands cheered, I knew to watch for the horse's bucking action, the cowboy's control of the horse, and how fluid their combined movement was.

I imaged AE beside me, slightly bemused that a long-ago show that was essentially a eulogy to a way of life had grown into an annual 10-day event that attracts over 1.2 million visitors a year and includes a daily parade, concerts, and some of the freakiest midway food imaginable. But I felt like maybe he had a special place in his heart for the bronco-riders—since it was his own riding injury that set him on the path to creating the Stampede. So we stuck around and watched.

Afterward we wandered through the agri-buildings, looking at the calves modern Albertan kids had raised and pondering how someone sheers a sheep so quickly. From there we headed to the Elbow River Camp where people from the Siksika, Piikani, Kainai, Tsuut’ina, and Stoney Nakoda First Nations shared their traditions and cultures—as they had since the very first Stampede.

As the day grew long, and the powwow drums echoed through the site, I watched kids in traditional regalia dance ancient dances with their elders. In the crowd, a little cowgirl stood transfixed by the ceremony and the majesty of a woman’s jingle dance. Watching her, I felt a breeze ruffle my hair. I imagined it was AE leaving my side—feeling he’d done his part. He’d shown me why he headed West and why he loved it and wanted to preserve it. It was up to me to decide if his contribution had meaning.

So I headed back to the midway, bypassing the Big Pickle Tornados and Bacon Onion Bombs in search of something healthier. As I ate, I watched as city folk, Canadian newcomers, First Nations people, and longtime ranchers (all decked out in their version of Western dress) celebrated the West at the party my ancestor started. I decided that as a legacy goes, this wasn’t a bad one.