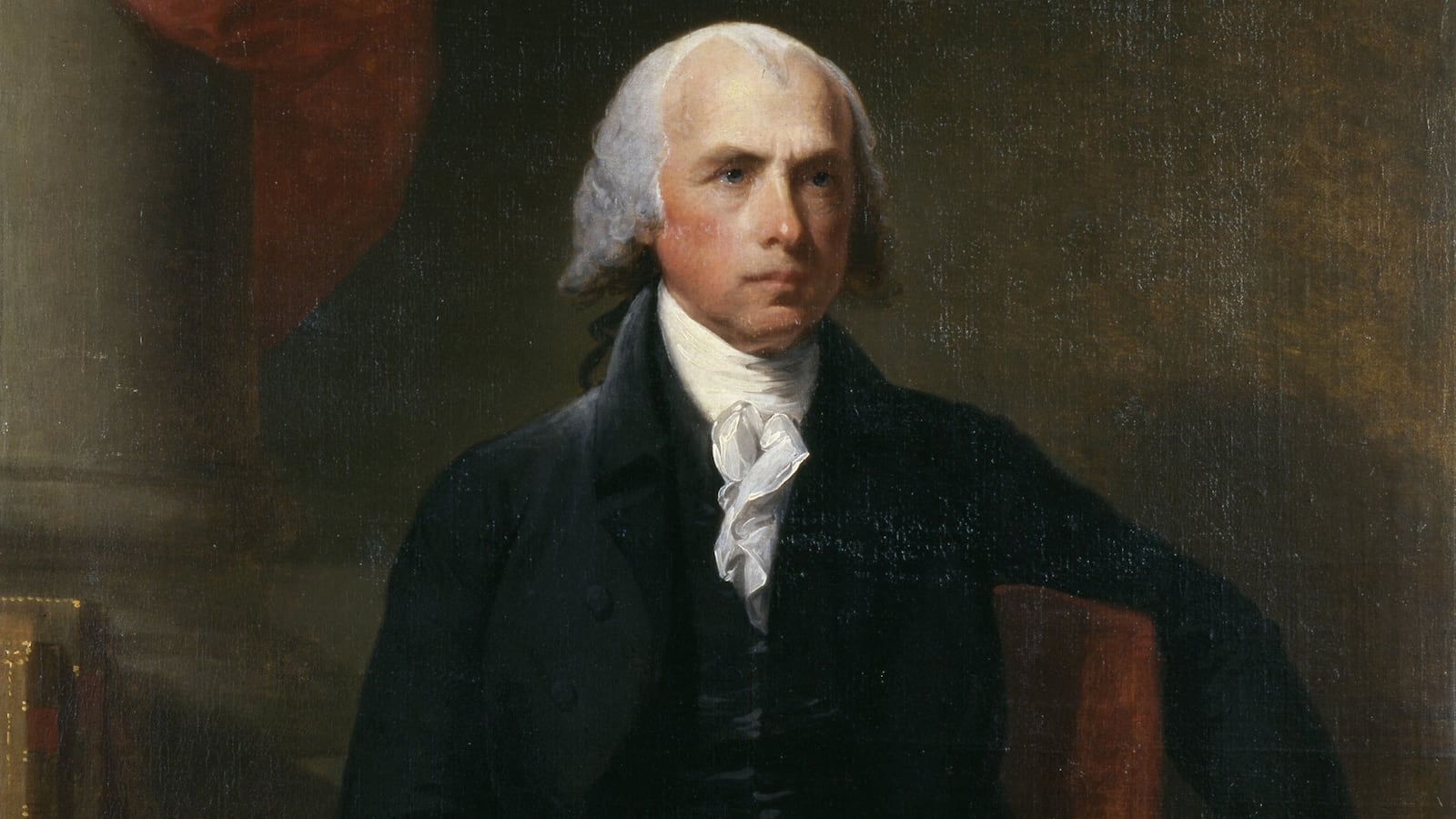

In 1784, when he was 33, James Madison, back from a three-year term in Congress, was a delegate in Virginia’s General Assembly. He weighed about 100 pounds, and he stood between five foot four and five foot six inches tall. He was kinetically anxious, almost feverish, and people seemed either to like or dislike him instantly. A fellow congressman wrote Madison that “there never was a crisis, threatening an event more unfavorable to the happiness of the United States, than the present.” An apocalyptic mood descended on Virginia—a frenzy, even, where ordinarily rational men became convinced that everyday affairs were all conspiring to destroy the very country itself. It did not help that the economy was in a free fall, and that the state’s government could barely even fund its daily operations.

He knew people pray in such moments; he was no exception. But he began to worry as the panic whipsawed in a menacing turn. Just eight years earlier, at the beginning of the Revolution, Virginia had what was thought to be a healthy religious establishment, numbering 91 clergymen and 164 churches and chapels. But while Great Britain had dragged the war on and on, a staggering decline had taken place. Now, only 28 ministers were preaching around the state.

Madison learned that Virginia’s former governor, Patrick Henry, saw a ripe political issue in the collapse of Virginia’s churches. Henry was perhaps the most astute and opportunistic politician in the country. In the years leading up to the Revolution, he led a raid on the British governor of Virginia’s stolen stores of gunpowder. He later declared, to instant fame, “Give me liberty or give me death!” in St. John’s Church in Richmond. In Henry’s first term as governor, in 1777, Madison eagerly joined his administration in the prestigious post of governor’s councilor. Yet in the years since the Revolution, much had changed. The British forces were brutal and predatory. The colonies were unable to join together and govern themselves. The jewel of the Revolution seemed to be turning into charcoal before his very eyes.

For Madison, nothing personified that disheartening transformation more than Henry himself. In the spring of 1784, he grimly watched from the floor of the General Assembly as Henry rose and proposed to force every taxpayer to dedicate a portion of his taxes to a Christian organization. (It was little consolation that Henry said that if a citizen refused to name such an organization, the state would put the funds to a government-run school instead.)

In the months that followed, Madison worked over the problem in his mind. From the Holy Roman Empire to the recent repression of Baptists in Virginia, he thought government had always been unable to provide impartial justice when supporting one sect—even Christianity, writ large—over another. More broadly, he wondered, a country with aspirations to join the pantheon of nations on a political theory of modern liberalism could not take such an obvious step backward. Yet the matter would require delicate political tactics, for the very danger of the proposal lay in its popularity.

Madison began devising a counterattack. He employed what I will call his “Method,” which was an interlocking set of nine tactics:

Find passion in your conscience. Focus on the idea, not the man. Develop multiple and independent lines of attack. Embrace impatience. Establish a competitive advantage through preparation. Conquer bad ideas by dividing them. Master your opponent as you master yourself. Push the state to the highest version of itself. Govern the passions.

He began taking notes on the back of an envelope for an assault on Henry’s bill. The true question, he wrote, was not whether religion was necessary. It was whether religious establishments were necessary for religion. The answer to that, he scribbled, was simple—“no.”

In November, Henry stood to speak in favor of his bill. He painted an antediluvian picture of the decline in American morals. He argued with passion that nations fell when religion decayed. Madison noted the reverberant power of Henry’s words among the gathered men, remarking years later on the distinct eloquence of the speech.

Madison then rose on the floor of the General Assembly. The building itself felt impermanent and makeshift. The cornerstone for a new capitol building nearby was scheduled to be laid in two months; the delegates knew they were on their way out of the aging and musty structure.

Small as he was, Madison appeared fit and muscular, if young for his age. He did not seem anxious, exactly—more tensile, as if he had captured and retained the energy of anxiety, like a coiled spring. Several of the men in the room knew of Madison’s pattern of succumbing to what he called his “bilious” or “epileptic” fits at moments just like these, and they must have watched with particular alertness for signs that he might quail and flee.

Reading from the scribbled outline, he assailed Henry’s assessment for being unnecessary and contradictory to liberty. Henry had blamed the downfall of states on the decline of religion. But Madison charged that states had fallen precisely where church and state were mixed. He challenged Henry’s assumption that moral decay was caused by the collapse in religious institutions; “war and bad laws” were instead at fault.

He concluded with what he called his “panegyric” on Christianity—an emotional endorsement of the power of faith. Henry’s assessment would actually “dishonor Christianity,” he claimed, by putting the state between man and God.

During this onslaught, many of the other delegates watched him uneasily. The topic was raw, particularly for those from Virginia’s more religious and conservative regions, where they had been raised to worship the Bible as the word of God and their ministers as the elders in their communities. Religion, to them, was an institution, a structure as necessary to society as the foundations were to their homes.

Yet many also held deep misgivings about Henry’s policy. To prevent a church from collapsing was one thing. To introduce a tax for that purpose was quite another. The idea felt illiberal and suffocating, at odds with the spirit of the new country they were trying to build.

But instead of leading the assembly to separate church and state entirely, Madison only succeeded in provoking them to consider supporting additional religions. A heated debate broke out among the delegates about the fact that only Christian organizations would receive the funds. They sent Henry’s bill to a committee of the whole, where the majority voted to change the word “Christian” to “religious.” But then the opportunistic and political sitting governor, Benjamin Harrison, with “pathetic zeal,” according to Madison, recruited a majority back to “Christian.”

Even though Madison had, in the words of a colleague, “display’d great Learning & Ingenuity, with all the power of a close reasoner,” he could not overcome Patrick Henry’s power in the assembly. In December, Henry’s bill passed its first reading (three were required for passage) by 47 to 32 votes. Henry seized the momentum and rammed through another measure to provide state incorporation to all Christian societies who applied. That bill passed 62 to 23.

Madison wanted to take Henry out of the arena entirely, and so he supported a motion to reelect Henry as governor. Henry accepted without fully thinking through the consequences. But now, for procedural reasons, he would be barred from voting for his own bill. Smiling, Madison informed his friend James Monroe that Henry’s elevation had “much disheartened” the supporters of the assessment.

That was just the beginning. In the next days, before Christmas, Madison completed his battle plan to crush the assessment once and for all. First, he needed a delay and he got it. On Christmas Eve, the assembly agreed to postpone the final vote until well into the next year, a pause that gave Madison almost a full year to grind away at the bill.

Christmas passed. The more Madison stewed on the bill, the more he hated it. He acidly told Thomas Jefferson the proposal was “obnoxious” for its “dishonorable principle” and “dangerous tendency.” But he predicted that its fate was, as best, “very uncertain”—meaning it could very well pass.

In mid-January, after the winter legislative session concluded, he took to the rutted, frozen red clay road that led from Williamsburg to Orange County, the site of Montpelier, where he still lived, unmarried, with his parents. What he heard in the coming weeks alarmed him—citizens, especially Episcopals and Presbyterians, were joining Henry’s lament for the collapse of religion in what he described as a “noise thro’ the Country.” But public opinion was also churning, reflecting the same restlessness that had given rise to the bill in the first place. By early spring, he noted that the zeal of some of the supporters had begun to cool.

Meanwhile, he worked. He composed a plan of attack to obliterate Henry’s “obnoxious” proposal—to burn up the weed, chop up its roots, and forever prevent its ability to spread. His outline on that envelope would be key.

In June, Madison completed an essay, which became known as his “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments.” Centuries after his death, it echoes as perhaps the defining declaration of the principle of the freedom of religion. His essay reveals the pure power of ideas in politics, handed from person to person like a talisman, like a scripture.

Madison delivered 15 separate assaults against Henry’s assessment. His strategy was reminiscent of George Washington’s famous encirclement of Lord Cornwallis three years earlier at Yorktown—a stranglehold from all sides. He launched with the most fundamental issue of all. Religion, Madison declared, belonged to the realm of conscience, not government. Men, considering only the evidence “contemplated by their own minds,” could not be forced to follow the dictates of other men. Religion therefore was, and must always be, unreachable by politics, by the state, and indeed by any instruments of human power. He explained that was precisely what Jefferson had meant by his already famous term “unalienable” in the Declaration of Independence.

The state cannot actually support religion, because religion’s strength depends on men’s mind, their reason, and their conscience alone.

Henry, for all of the protestations against a strong central government he would later pronounce on behalf of the anti-Federalists, saw problems through the prism of government. Religion was under siege; the state must defend it. But with this first attack, Madison had succeeded in yanking the prism away and revealing a brilliant and very different new world. Not only was Henry’s basic position implausible; it could not succeed.

He then thrust 14 more arguments into the flank of Henry’s wounded bill.

He declared that the assessment violated the principle of equality by treating the religious class differently from others.

He lambasted the “arrogant pretension” that the civil magistrate, represented by the legislature and tax authority, could be a “competent judge” of religious truth.

He demanded, of 15 centuries of the legal establishment of Christianity, “What have been its fruits?” Sarcastically, he observed that state involvement in religion had generated only pride and indolence in the clergy; ignorance and servility among the laity; and, in both, superstition, bigotry, and persecution.

Madison then effortlessly moved to a new front. A bankrupt farmer named Daniel Shays had recently led a violent uprising of debtors in Massachusetts, which had sparked widespread anxiety among the landed gentry who were well represented among the delegates in the room. Madison ominously suggested that Henry’s assessment could lead to public unrest. What “mischiefs may not be dreaded,” he asked, if the “enemy to the public quiet” were “armed with the force of law?”

Then, Madison swiftly shifted from disaster to idealism. Henry’s bill, he declared, was simply “adverse” to the “diffusion of the light of Christianity.” He meant that enlightenment was actually available to Virginians; they could support religion by opposing Henry’s bill. Henry, obsessed with taxation and government involvement, was in effect standing in the way of faith.

He concluded on hope rather than fear. The freedom of religion, he said, was a “gift of nature.” If Henry’s bill passed, the legislature might just as easily “swallow up” the executive and judiciary branches, as well as all the individual freedoms. If, on the other hand, Virginians met their duty to God, to the “Supreme Lawgiver of the Universe,” they could “establish more firmly the liberties, the prosperity and the happiness of the Commonwealth.”

For an uncommitted Virginian handed one of the proliferating copies of the essay, Madison’s Remonstrance had a dazzling effect. It was as if by so thoroughly ribboning Henry’s bill, he had allowed sunlight to stream through it. Henry was powerless to stop the Remonstrance, whose contagious force began growing.

But a strange obstacle quickly appeared. Madison’s friends wanted to reprint his essay as a pamphlet for mass distribution, but he amazed them by announcing that its authorship must be kept secret. They did the best they could to respect his frustrating and eccentric request. After printing copies in Alexandria, George Mason sent them to friends and neighbors with a cover letter requesting anonymity for the author. He explained that he was “a particular Freind, whose Name I am not at Liberty to mention.” Madison himself mailed a friend a copy, while demanding that “my name not be associated with it.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—the Remonstrance’s alluring anonymity, the civil movement against the assessment quickened.

Initially, 13 separate petitions supporting the Remonstrance sprouted up around the Commonwealth, gathering 1,552 combined signatures. A friend from Orange County told Madison he had convinced 150 of “our most respectable freeholders” to sign a petition—in a single day. Twenty-nine other petitions went even further than Madison’s, asserting that Henry’s proposed act contradicted the “Spirit of the Gospel,” and attracted another 5,000 signatures. In the end, over 10,000 Virginians signed some sort of an anti-Assessment petition.

In November 1785, a little over a year after Henry had first introduced a real threat to religious liberty in the new nation, the Virginia delegates, gathered in Assembly—with Governor Henry watching, powerless, sent Henry’s bill to a legislative “pigeonhole” where it was left to die—killed by James Madison. Meanwhile, Madison had developed the template for the principle he would embed in the Bill of Rights five years later: “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

The man who could make such an impact through a single essay—through paper rather than performance—has been profoundly misunderstood. Madison seemed to be less attractive, seductive, amusing, engaging, and passionate than the other Founding Fathers. This—along with his own stubborn refusal to pursue fame—might explain his decrepit legacy. But consider an additional hypothesis: that Madison was not actually as uninteresting as he often appeared to be. Instead, his unstinting self-control was a mask, or a shell, for his sensitivity. The fact is that he was painfully self-conscious, frequently consumed by anxiety, and often, in his public life, more focused on getting by than on performing for his peers, let alone history.

His friends recognized this all along. Staying for months at a time at a well-regarded boardinghouse in Philadelphia, Madison formed a trusting friendship with Eliza House Trist, the daughter of the owner. The two maintained an intimate correspondence for many years later. Madison often wrote her, with empathy, about her family, her health, and her life in general, and was devastated when her husband died, soliciting help for her from friends.

Trist gladly returned these favors. When Madison left Philadelphia after his first term in Congress, Jefferson felt he could easily be elected governor of Virginia, if he wanted the post. Jefferson mentioned that fact to Trist in a letter. She responded with a note containing a profound insight. Madison, she wrote, deserved “everything that can be done for him.” But she thought it would be “rather too great a sacrifice” to make him governor. That was because her friend had a “soul replete with gentleness, humanity and every social virtue.” And she was, she said, “certain” that in the process of a political campaign, “some wretch or other” would “write against him.” “Mr. Madison,” she wrote, was “too amiable in his disposition to bear up against a torrent of abuse,” she concluded. “It will hurt his feelings and injure his health, take my word.”

Trist’s tender concern for her friend reveals as much about his basic nature as about his bond with friends and allies, which helped him survive and thrive in what was, for him, an unnatural arena. Eliza House Trist wanted Madison to stay as far as possible away from politics. That he ultimately decided to plunge into a realm so perilous for his well-being suggests the high stakes he saw in the enterprise. He was willing to build the government the country needed, even if he might jeopardize himself in the process.

Perversely, through history’s increasingly dusty lens, Madison’s mask has become more famous than the man underneath. Our general impression remains as severe as the title of a 1994 book: If Men Were Angels: James Madison and the Heartless Empire of Reason. Most Americans, if they know anything about him at all, see him as calculating, intellectual, politically astute, dry, and remote. This pattern has lasted for a long time. In 1941, in his one-page preface to his authoritative four-volume history of Madison’s life, the historian Irving Brant wrote, “Among all the men who shaped the present government of the United States of America, the one who did the most is known the least.”

But to his contemporaries, Madison was never dry or remote or calculating. In June 1824, when Madison was 73 years old, an itinerant bookseller named Samuel Whitcomb met with him. He wrote that “instead of being a cool reserved austere man,” Madison was “very sociable, rather jocose, quite sprightly, and active”; yet he also had “a quizzical, careless, almost waggish bluntness of looks and expression which is not at all prepossessing.” Yes, Madison was cold to strangers—as well as to history. But to those he invited in, his friends and allies and coadventurers, he was warm and full of life, seductive, hilarious, and even entrancing. The stunning story of his victories is simply incomprehensible without the passion, charisma, energy, humor, and fierceness of Madison the actual man.

After the ratification of the Constitution, Madison spent another four decades in public life—as a US representative of Virginia in Congress, as secretary of state to President Thomas Jefferson, and as president, for two terms. As an outgoing president, he was quite popular, despite his unsure conduct of the War of 1812, and he was also succeeded by James Monroe, a member of his own party, which usually means that the outgoing president did his job pretty well. Despite his morbid hypochondria, Madison outlived his father, who died at the age of 77. He outlived George Washington. He outlived Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who both died on July 4, 1826. He lived so long that he was alive well into the presidency of Andrew Jackson.

Yet he achieved his summit in his earlier years, as a young man. Irving Brant was always troubled by the elusiveness of Madison’s younger self. “What of the James Madison who helped to carry on the War of the American Revolution and at the age of 36 earned the title of Father of the Constitution?” Brant asked. That young man, he said, “is known only through a backward projection of his later self, and therefore is not known at all.” Brant concluded, “When a man rises to greatness in youth, it is with his youth that we should first concern ourselves.”

At long last, this book attempts to answer Brant’s call. Madison’s story, and the broader ideas he fought so hard and well for, can help democracy at a moment of unique crisis. Franklin Delano Roosevelt said the only thing we had to fear was fear itself. Today, we have to fear cynicism about leadership itself. Our era teems with a series of unenviable superlatives. The 113th Congress was the least effective in history. It was also the most unpopular in recorded history. In their best-selling It’s Even Worse Than It Looks, the political scientists Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein argued that a culture of hostage-taking in the Republican Party was largely to blame, coupled with systematic trends in campaign finance and fund-raising, and the disappearance of friendships between senators and representatives. The authors recount then-House minority leader Newt Gingrich’s decision, in 1994, to run against incumbent Democrats by pursuing “relentlessly the charge that Congress was corrupt and needed to be blown up to change things.” Gingrich developed a tactical memo instructing candidates to use certain words when talking about the Democratic enemy: “betray, bizarre, decay, anti-flag, anti-family, pathetic, lie, cheat, radical, sick, and traitors.” Today, a similar nihilism has appeared in many of the actions of legislators and activists associating themselves with the “Tea Party” movement. And there are striking parallels between the threats posed by Patrick Henry and certain of the anti-Federalists in young Madison’s time and the “Tea Party” forces in American politics today.*

The general dissatisfaction with our political leaders has migrated into many other branches of leadership. After departing as secretary of defense to President Barack Obama, Robert Gates described members of Congress en masse as “uncivil, incompetent at fulfilling their basic constitutional responsibilities (such as timely appropriations), micromanagerial, parochial, hypocritical, egotistical, thin-skinned and prone to put self (and re-election) before country.” Amid such scorched earth, it has become disconcertingly difficult to cite leaders we would readily describe as “statesmen.” In dozens of conversations with current and former members of Congress, journalists, academics, and political activists while researching this book, I watched as people struggled to cite an example of a statesman. This was not a problem even a generation ago, as Ira Shapiro points out in The Last Great Senate, where figures, including Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Frank Church, Margaret Chase Smith, Hubert Humphrey, Jacob Javits, Gaylord Nelson, Scoop Jackson, Ted Kennedy, George McGovern, William Proxmire, and Robert Byrd, all sought to elevate the United States through the U.S. Senate. Bipartisanship was common, as were long campaigns on difficult legislative issues where the legislator would develop personal expertise, as were serious deliberative sessions where lawmakers would personally take charge of negotiating the fine details of a generational issue. For all of these, a consensus on the need for statesmanship was the sine qua non.

If there were more statesmen in America, and more citizens who looked up to them and bolstered them, then our country—like Madison’s—could advance beyond the sclerosis and mutual hatreds that have paralyzed us. Those problems particularly afflict one institution in particular—the U.S. Senate—which was designed precisely as a home for statesmen, yet has become infected by the same virus that has invaded our other institutions. For we desperately need venues where serious men and women contest each other in depth on the country’s critical issues, where they assemble coalitions, battle valiantly, and accept defeat, when it comes.

The story of Madison’s leadership is relevant not just for politics, but can be applied in business, in nonprofit management and social entrepreneurship, in education, in social media campaigns, and in virtually every arena where leadership matters. Any group facing a seeming total failure to rise to a challenge would do well to study Madison’s approach of a sustained campaign to destroy bad ideas and raise up good ones, through conviction, preparation, and self-governance.

Statesmanship is an old-fashioned solution for a very new world. Leadership has fallen somewhat out of fashion in political science. In a social media age where we think more readily of networks and of community organizing as principles for power, leaders seem antiquated, much less statesmen. As the leadership scholar Warren Bennis has written, “A decade from now, the terms leader and follower will seem as dated as bell bottoms and Nehru jackets … What does leadership mean in a world in which anonymous bloggers can choose presidents and bring down regimes?”

But if young Madison’s story proves anything, it is that leadership—and statesmanship—are as essential to a healthy democracy as constitutionalism. Indeed, both are required—from the bottom up, engaged citizens; and from the top down, statesmen who challenge and lead.

As the historian Jackson Turner Main has noted, the anti-Federalists were a large tent of many thousands of political actors, with a wide range of motivations and political philosophies. Some were motivated by a good-faith concern for the common good. Among those general interests were a worry about the proper balance of power between federal and state governments, on the assumption that “to vest total power in a national government was unnecessary and dangerous .” Others wanted to protect private rights and liberties “from encroachments from above .” Still others focused on the proper functioning and powers of the Constitution’s branches of government. Yet many anti-Federalists also pursued private or special interests, whether commercial, parochial, or personal.

This piece was excerpted from Becoming Madison: The Extraordinary Origins of the Least Likely Founding Father by Michael Signer (PublicAffairs, 2015). Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Michael Signer is the author of Becoming Madison: The Extraordinary Origins of the Least Likely Founding Father and a principal of the Truman National Security Project.