Today's headlines: Coronavirus Spreads! Stock Market Tumbles! Chaos in Washington!

Ordinarily, these crises would haunt my dreams. And yes, they still do to some extent. But not as much as they ordinarily might, because for me these are not ordinary times. Not since James Taylor entered my life.

Yes, that James Taylor: Five-time Grammy winner, Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient, Kennedy Center Honoree. Gone are Morning Joe and CNN New Day. Instead, I’m checking James Taylor’s Twitter Page. This can’t be right! I’m as old as he is, a retired college professor, author of five respected books, a contributor to The Daily Beast. I’m too old to be a groupie.

It all began on Friday, Jan. 24, 2020, with an article I found in Rolling Stone: James Taylor would soon release a new album, American Standard. None of the songs were his. It was his salute to the “great American Songbook,” 14 classic songs by America's greatest songwriters—Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Loewe, Frank Loesser, Jerome Kern, Henry Mancini, and M.K. Jerome and Jack Scholl. That’s when my heart skipped a beat. There were songs from Oklahoma, South Pacific, Guys and Dolls, and… Katnip Kollege, a Warner Brothers cartoon.

I leaped to my feet: M.K. (Moe) Jerome was my grandfather, a songwriter first on Tin Pan Alley from 1911 to 1929, when Warner Brothers hired him to write songs for their movies. (I introduced him to readers of The Daily Beast in an article in August 2017.)

Taylor had selected one of Moe Jerome’s songs, “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log,” for inclusion in his album alongside such classics as “Moon River,” “The Nearness of You,” “Teach Me Tonight,” “Ole Man River,” and other standards. That such a heavyweight artist would record one of my grandfather’s most obscure songs left me puzzled as well as excited.

Michael Feinstein, the Ambassador of the Great American Songbook, kindly gave The Daily Beast the “original uncut soundtrack“ of “As Easy As Rolling Of A Log” which includes a verse never heard before outside the studio. Enjoy!

In an interview with Jane Pauley on CBS's Sunday Morning on Feb. 2, Taylor explained how he made his choices. The songs “were part of my family's record collection, the first music I heard as a kid growing up in North Carolina,” he said. He listened to these “favorites” over and over and learned to play the guitar on them. He also considered them “so smart and so capable... that they need to have a presence in the life of music.” In the background played several of the album's songs, including “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log.” It sounded wonderful, arranged simply with guitar, clarinet and drums, ending with Taylor whistling it. Its infectious melody spoke out to a 21st century audience. Or so I hoped.

But a mystery remained. How did my grandfather’s song end up in that group of classics? It was written in 1937 for a low-budget “B movie” but did not appear on a record. A year later, it wound up in a cartoon. But again, it was not recorded, so there was no permanent vinyl edition. The cartoon joined movies and shorts in theaters in 1938, a decade before Taylor was born, and was reissued to theaters in 1945, but again Taylor could not have seen it then. Nor could it have been part of the Taylor family record collection, like the other songs. It could be found in Warner Brothers cartoon collections on DVD released in 2004, and, by the late 2000s multiple copies were available on the Internet and on YouTube. Could Taylor have seen it there?

A more important mystery also remained: How did two songwriters who seemed totally different somehow connect? My grandfather was born in 1893, grew up in New York City in the early 20th century. His parents were Viennese immigrants, his father first a barber, then a tailor during Moe’s childhood. For Moe, music became a means of escape from poverty and family problems—his parents didn't want him to go into show business. He quit school and left home to become first a piano player in city nickelodeons, then a song plugger for Irving Berlin and a songwriter on Tin Pan Alley. Later, Warner Bros. brought him to Hollywood.

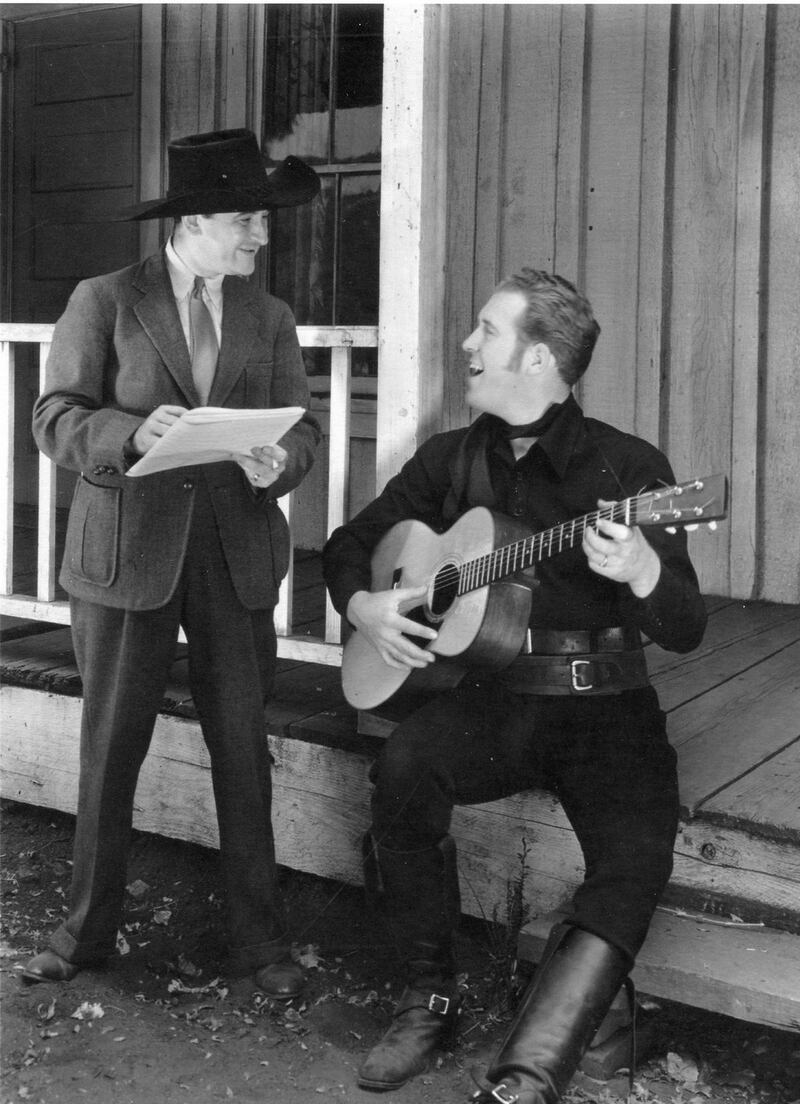

Moe the cowboy with Dick Foran on “Moonlight On The Prairie” (1935)

Courtesy Gary MayTaylor, on the other hand, was a baby boomer born in affluence in 1948. His father was a doctor who became Dean of the University of North Carolina Medical School. But Dr. Taylor was a troubled man who turned to alcohol to ease his pain. His marriage collapsed and the Taylor children became emotionally ill. James’ depression forced him to leave prep school and spend ten months in a psychiatric hospital. Drugs, including heroin, became the means with which he eased his pain, and he frequently returned to institutions. As it had been for Moe, music became a means of escape, and Taylor found early success in 1968 with the Beatles' Apple Records. But James and Moe's link was tenuous. How did two such different men share similar musical tastes, if, in fact they did? I needed to find out.

I began my search at Taylor’s website. There, in the lower left-hand corner of its front page, was an icon, an old fashioned typewriter reading “send James an email.”

One click and a page appeared. I filled it out, explaining that I had just learned that my grandfather's song was in his forthcoming album, told him what I knew of its origins in film and cartoon, thanked him and co-producers Dave O’Donnell and John Pizzarelli for giving “Log” a new life, and asking how he had come to include it among such timeless songs. Would he reply? The site warned that while he loved to read his e-mails, he could not always answer. So, I also wrote Dave O'Donnell, whose e-mail address was online. Would either respond? It was Sunday, Feb. 2—Super Bowl Sunday. Nobody was home except me.

James Taylor did not respond, but within a half hour I received replies from Dave O’Donnell and Ellyn Kusmin, Taylor’s personal assistant. Both were happy to hear from me and to learn what I knew about the origins of the song. O’Donnell, an esteemed musical producer, engineer, and sound mixer, had worked on Taylor’s last six albums. He solved my mystery. “James remembered [the song] from seeing ‘Katnip Kollege’ when he was young,” O’Donnell wrote. “It always stuck with him and he [wanted] to record it someday and finally the right project arrived.” They found the cartoon on YouTube (“a real treasure”) and Taylor created a “great arrangement.” “It’s one of James’ favorite songs on the album.”

Ellyn Kusmin confirmed what I had learned from O’Donnell. She described Taylor, O’Donnell, and the third producer, John Pizzarelli, a master guitarist, seated at a table in Taylor’s studio (called the Barn), closely watching the cartoon on a laptop.

The Tunemill: Moe Jerome (at piano) and Jack Scholl (1937)

Courtesy Gary MayTwo days later, on Feb. 4, Taylor released on YouTube Making of American Standard, a nine-minute documentary in which he explained in more detail how he came to make the album. He began in the fall of 2017, calling Pizzarelli and O'Donnell to his home in western Massachusetts. Because he always wrote and arranged on the guitar and Pizzarelli, like Taylor, played it superbly, they decided it would be a two-guitar album with additional instruments depending on the song, and a few back-up singers, They built an echo chamber from a cargo container to create “real analogue echo.” Taylor and Pizarelli cut the basic tracks with O’Donnell.

The songs were the “musical foundation” of his generation, he explained. Today’s songs were designed to be sung by their writers, people went to see them performed only by them. The songs of the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s were the “pinnacle of American popular music,” Taylor believed. Richly melodic with “clever” and “sophisticated” lyrics, they were meant “to stand on their own,” to be sung by anyone.

He played a bit from several of the songs and commented on them and, toward the end, there came a scene from the cartoon Katnip Kollege with Johnny Kat and Kitty Bright singing “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log.”

“This song is unusual,” Taylor said. “It comes from a cartoon that I remember from being a kid. The tune stuck in my head for years.” “A hidden gem,” O'Donnell interjected. “The music either strikes you or it doesn’t,” Taylor continued. “And you may not know why. But it’s because some really smart people put together the lyric and the melody...”

When Taylor’s fans first learned of his new album, some were disappointed that it contained no original material but only “covers,” his own versions of other people’s songs. “Come on James, you’re so much better than this,” complained one listener after Taylor started releasing the songs on YouTube: “Teach Me Tonight,” and then “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log.” “Elevator music with lyrics,” noted another, while a third thought “Log” was “a Christmas song.”

Other listeners, hearing “Log” for the first time with Taylor’s acoustic guitar arrangement, responded quite differently. “Pure joy,” wrote Brian Bopp. “That’s a tune that will stick around in my head all day.” Many agreed, calling the song “amazing,” “awesome.” “What a great tune to rescue from oblivion,” declared Jonathan Vieker.

Taylor talked about “Log” again during an interview with NPR's Lulu Garcia-Navarro on Feb. 9. “Do you have a favorite on this album that you can tell us about?” Navarro asked him.

“There’s a... simple ditty of a song that no one ever heard, that was part of a cartoon from my youth called Katnip Kollege,” Taylor replied. “It was about a college full of swinging cats—one who’s a dunce and can't get rhythm but suddenly is bit by the rhythm bug and suddenly swings. This song has stuck in my memory for these 50... or 60 years.” Then he sang a few bars of the song. Garcia-Navarro called it “a very happy song,” so different from Taylor’s own work, which was influenced by his father’s alcoholism, his parents’ divorce, and his own emotional problems. “It is,” he agreed.

But for Taylor, it wasn’t simply a matter of remembering his youth and the music that first provided an escape from misery. Those great songs were a tribute to that generation of songwriters who, he said, were given “a task [to] move the action along, [or] make emotional points [in a play or movie]. It was amazing how they could apply their talents with such [specificity].”

Without ever meeting Moe Jerome, James Taylor instinctively understood the nature of my grandfather’s job as a staff songwriter at Warner Bros.: writing songs not as a means of self-expression, like Taylor and most of today's songwriters, but to fulfill the needs of a producer or a director who needed a song or just music to fit a cinematic situation.

Taylor has often admitted that his songs were inspired by his family's personal history. For Moe Jerome, inspiration had little to do with his work.

“Most people picture us [Jerome and Scholl] as two happy go lucky guys who sit around from 9 to 5 and play the piano, sing, and have a grand old time,” Moe once told a journalist. “But when you turn out a couple hundred tunes a year, it becomes more of a business... We have to work pretty fast, and we don't expect all those tunes to be hits... [T]hey’re pretty much specialized numbers that haven't any commercial possibilities outside the picture.”

So it was with 1937’s “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log.” Understanding the song”s birth provides a window into the unknown story of a studio songwriter’s life in Hollywood's dream factories during the so-called “golden age” of American cinema. For Moe Jerome, it was more factory than dream and little about it was golden. Indeed, life was so stressful that, according to family lore, the first thing he did when he returned home after nine hours at the studio was to rush to the bathroom to vomit.

Jerome and Scholl began 1937 as the most prolific songwriting team on the Warner’s lot. During the previous six months they had written a total of 43 songs, more than any other Warners songwriters. Variety called them “The Tunemill.” And 1937 would prove to be another very busy year, in which the duo would contribute 59 songs to 20 movies and 3 shorts. They wrote for every genre—westerns, musicals, romances, melodramas, historical dramas, and comedies.

Physically and temperamentally, they could not have been more different. Moe was short, slim, and, at 42, balding. Jack was 33, tall, and weighed over two hundred pounds. Moe’s father had been a barber, Jack’s a Broadway producer. Jack attended West Point, left after a year and headed to Broadway, where he wrote operettas. On a lark, he and his new bride drove to Hollywood in 1933. Jack acted in westerns, then joined the music department at Warner Brothers. While Moe tended to be quiet and Jack garrulous and athletic, they found that they were compatible, at least at the studio.

Moe Jerome playing for Ann Sheridan (L) and Jane Wyman(R) on “The Doughgirls” (1944)

Courtesy Gary MayRobert Taplinger, director of Warner Brothers’ publicity department, once observed them on the job: “Moe works out the melodies on their piano. Scholl sometimes hums idly, or he may finger a series of chords on a ukulele... After Jerome has worked out the music, Scholl writes the words. But... when it becomes necessary to sing the words and ‘sell’ the song, Jerome has to do it. Jerome’s voice isn't the same beguiling tenor as that of Scholl, but... after Scholl writes the lyrics for their song, he generally forgets [them], and Jerome, who forgets nothing, has to sing them. The intentness in Jerome’s makeup enables him to ‘sell’ the melody, plus the words, because he believes so implicitly in the hit qualities of their music after they write it.”

“As Easy as Rolling Off a Log” was one of four songs written for Over the Goal, produced by Bryan “Brynie” Foy, supervisor of Warner Brothers’ low-budget film unit, known as “Keeper of the B’s.” No film genre was safe from Foy: He made them all—comedies, dramas, musicals, and westerns. “I don't want to do a script better,” Foy once said, summing up his philosophy, “I want to do it again.” Moe contributed songs to or scored 33 Foy movies between 1935 and 1940.

In Over the Goal Foy took on football. Football mania had swept the country in the ’30s and Hollywood fed the frenzy. Every studio had a football movie starring their biggest stars. There were even shorts featuring the Green Bay Packers and the Chicago Bears, as well as cartoons.

Over the Goal was set on the campus of a financially troubled college that is promised a huge financial bequest by a wealthy alumnus if it will defeat its chief rival on the gridiron. “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log” was meant to be the major production number, but that's not the way it turned out. In movies, it is the star, not the story, that drives the music, and in Over the Goal the star was a Hollywood newcomer named Johnnie (Hot Stuff) Davis.

A young trumpet player and actor, Davis specialized in scat singing, the improvisatory vocal style popular in the ’30s. So, Moe and Jack had to write a number to fit his talents. That doomed “Log” as the film's top song, which instead became “Scattin’ With Mr. Bear.” Total screen time for “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log” was 33 seconds. More screen time—and two production numbers—went to “Scattin’ With Mr. Bear” because it fit the plot and showcased Davis's vocal and trumpet skills.

“As Easy as Rolling Off a Log” might have quietly expired but for Warner Brothers’ habit of never getting rid of any property it owned and remaking films as shorts or cartoons. Moe’s songs can be found playing in the background or sung by Bugs Bunny, Elmer Fudd, et al, in approximately 90 of the studio’s Merrie Melodies or Looney Tunes cartoons. So, it’s not surprising that in 1938, studio animators decided to use existing soundtracks from other films in a cartoon about a group of felines taking a course on Swingology at Katnip Kollege. This is the cartoon that Taylor first saw as a child, and it includes a full rendering of “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log.” It was this version that stuck in Taylor’s memory for decades, until he finally put his own rendering on an album.

But this story is far from over and it’s not clear if the ending will be a happy one. Will a song 83 years old, even with a new arrangement and sung by an artist who has sold millions of records, appeal to a modern audience at a time when other top singers such as Justin Bieber and Lady Gaga have released new albums? Perhaps that very thought has occurred to Taylor, since in recent appearances on Late Night with Seth Meyers, Late Show with Stephen Colbert and Live with Kelly and Ryan, he’s chosen to sing such well known classics as “Teach Me Tonight” and “Almost Like Being in Love.”

It has occurred to me in the midst of all this that I’ve become my grandfather. As a child, I remember that following his retirement from Warner Brothers, he spent his days waiting for a “plug”—someone singing one of his songs on radio or television—and fighting the dominance of Rock ’n’ Roll, which he hated. Now, as I listen to Bieber’s “Intentions” and Lady Gaga’s “Stupid Love,” I respond as my grandfather did to ’50s tunes: “It’s just noise.” Nobody can sing those songs except them.

So whatever the fate of “As Easy as Rolling Off a Log” may be, three cheers for James Taylor who brings alive 13 of the most beautiful songs of the 20th century and a “hidden gem” from Hollywood to a new generation, whether they appreciate them now or not. Some day they will.