It was an October day in Miami, 1985, and Leonel Martinez didn’t want to die.

Margarita Escobar—a Colombian woman known as La Doctora and rumored to be a distant relative of Pablo Escobar—had paid Martinez, a construction magnate, a hefty sum to move 12 duffel bags of cocaine from The Bahamas to Miami on his luxury yacht. The load got intercepted en route, though, and La Doctora wanted her money back. But Martinez didn’t have it.

So she called him up and said she would be visiting his office. Martinez did the natural thing: He bought a Cadillac limousine, sent it to pick up her and her bodyguard at the airport—in an effort to project wealth he didn’t quite have—and welcomed her to his office.

She demanded he produce the cash. He didn’t have it, and he offered her 10 condominiums instead. But that wasn’t good enough. Give her the money, she said, or she’d kill him.

“You can kill me, or you can wait,” he replied.

She decided to wait, and she flew back to Colombia. Then Martinez got to work rustling up the thousands he owed her.

Overlooking that conversation was a wall plastered with pictures of Martinez glad-handing some of South Florida’s most powerful political luminaries. That’s because the drug trafficker—according to a retired DEA agent and a retired Metro Dade police officer who worked to hunt him down—had a knack for creating the illusion of intimacy with elected officials.

A few of those officials had the last name Bush.

But those donations didn’t get him much.

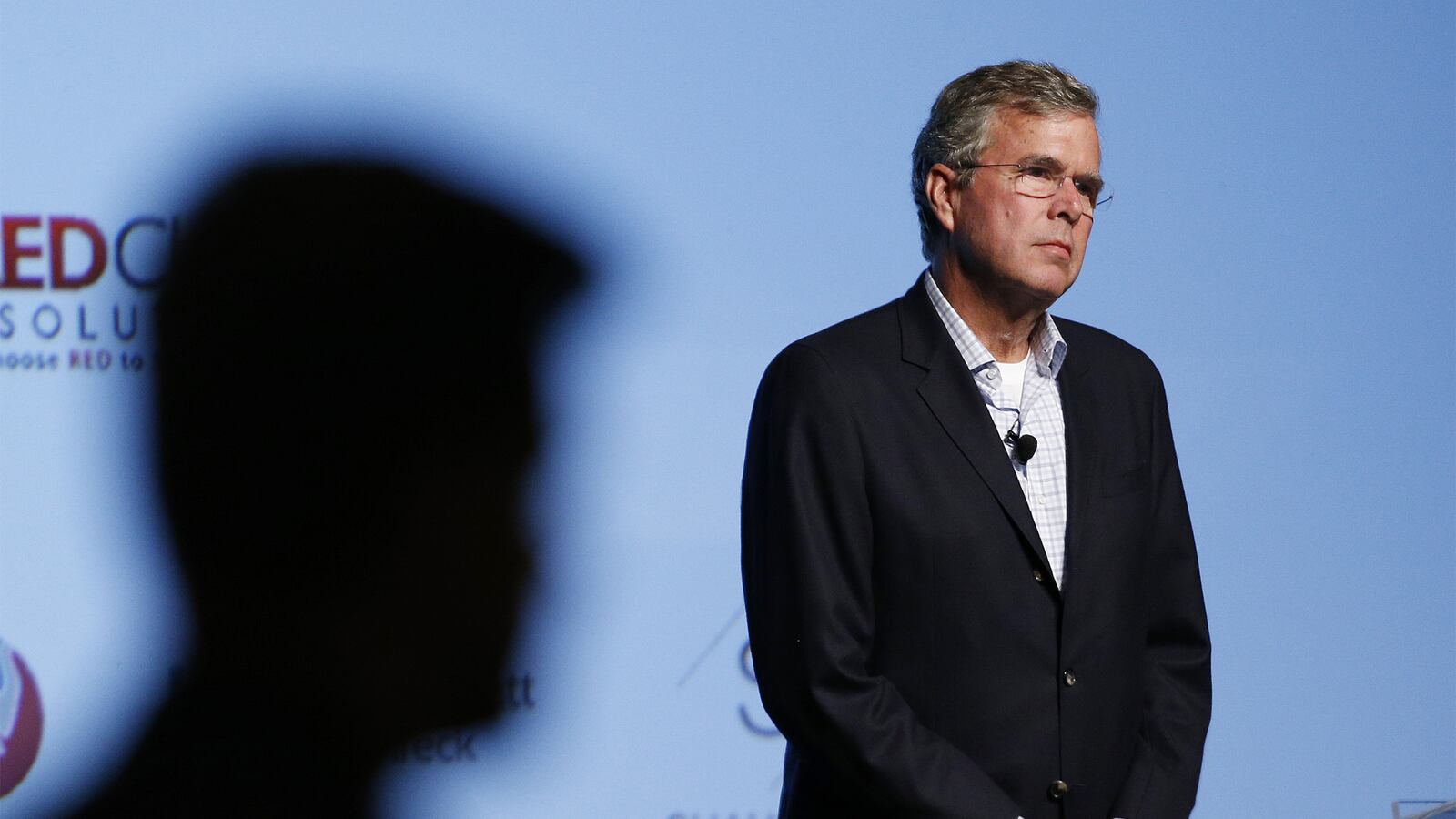

In fact, as governor, Jeb Bush became a favorite of drug warriors. He mirrored his father’s tough-on-drugs tactics in Florida, won the loyalty of cops and DEA agents, and showed the limits of money in politics.

When Jeb arrived in South Florida after the 1980 presidential campaign, it was a crazy time.

The use of drug money in politics was commonplace.

In fact, his dad’s presidential campaign and the Jeb-helmed Dade County Republican Party both took contributions from Martinez, and faced minimal political repercussions when Martinez’s true career was revealed.

Eduardo Gamarra, a professor in Florida International University’s department of politics and international relations, said at that time Southern Florida was so saturated with cocaine-tainted cash that it would have been odd if none of it could get traced to Jeb.

“That’s just the way things were in the 1980s,” he said.

Gamarra added that grip-and-grin photos with drug dealers didn’t immediately mean the politician was in league with them. Even then-state attorney Janet Reno appeared in a photo with Martinez when he was being investigated for bribery.

Martinez moved from Cuba to Miami when Castro rose to power, and he proceeded to build a successful construction business—with a lucrative marijuana- and cocaine-trafficking business on the side.

He also made a number of contributions to the Dade County Republican Party when young Jeb Bush chaired it, as Jack Colhoun detailed in an essay in the anthology Covert Action: The Roots of Terrorism. Martinez won respect in Republican circles and, according to his former defense attorney Ron Dresnick, even managed to snag a photo with Jeb. It was never released.

This came at a time when Jeb was laying some of the groundwork for the GOP’s eventual and total takeover of state-level politics there. In 1984, Politico wrote, 4,000 Democrats became Republicans and 74 percent of Hispanics to join the voter rolls that year registered with the GOP.

That success ballooned, and Bush carried Miami-Dade in both of his successful gubernatorial campaigns. His impact in the Sunshine State is hard to overstate.

And a tiny little statistically insignificant sliver of it was thanks to coke money.

By 1989, Martinez was unmasked as a narcotrafficker. The Miami Herald reported that he had promised to give a covert Drug Enforcement Administration informant a dump truck worth $80,000 and five lots worth $120,000 in exchange for 300 kilograms of cocaine. The Herald also noted that, in a government affidavit, between 1981 and 1989 Martinez and his team endeavored to move hundreds of pounds of marijuana and “multi-hundred kilogram shipments of cocaine” into Southern Florida. As one does.

The Martinez case was representative of a South Florida cocaine problem of cartoonish proportions—a culture where Jeb’s political ambitions first began to flourish.

“It was a nuthouse,” recalled Tom Raffanello, a former Special Agent in Charge of the DEA’s Miami Field Division, who had that position for three years of Jeb’s governorship there. “We averaged two drug-related shootings a month for almost two years. Everybody had a gun. Everybody was pissed off all the time.”

Tony Kost, a retired Metro-Dade Police Department detective who worked to apprehend Martinez, Dominic Albanese (a retired DEA agent who worked on the investigation), and Raffanello all praised Jeb’s work to continue the prosecution of the Drug War that started when his father, George H.W. Bush, was vice president for Ronald Reagan.

It’s an interesting story of the failure of money in politics; though Martinez managed to donate his way into the good graces of South Florida Republicans, some of his favorite politicians ended up being the most dogged foes of his industry.

Albanese said that Jeb Bush’s support of the War on Drugs—despite inadvertently appearing in a photo with a powerful drug trafficker—speaks to his integrity.

“I can’t say enough good things about what the Bushes did for the anti-drug department, I’m telling you now,” he added. “I know where we would have been if it wasn’t for them. We’d be in deep kimchi right now, I’m telling you, with the drug problems.”

Jeb Bush appointed the state’s first drug czar, Jim McDonough, just a month after he assumed office. McDonough’s responsibilities included coordinating statewide efforts to curtail the import and distribution of narcotics. Bush prioritized streamlining the communications between different agencies and governments—local, state, and federal—to make anti-drug efforts more efficient.

Gamarra, a Democrat, also said taking Martinez’s cocaine cash shouldn’t taint the Bush family’s anti-drug legacy.

“It’s kind of popular to go around saying we’ve lost the drug war,” he said, “but South Florida really demonstrates how they built up the correct kind of legislation—financial controls and so on.”

“You’re not going to find an airplane flying into the Everglades dumping cocaine,” he added. “Miami has drug problems today but this is not the 1980s by any stretch of the imagination.”

Gamarra described Bush and his team as “the best drug warriors in town.”

“Just like today everybody has to be a badass when it comes to fighting terrorists, the ’80s and ’90s were really the same,” he continued. “You had to demonstrate that you were a drug warrior, that you were in favor of all the extreme kind of measures to stop drugs coming into the United States.”

Data from the U.S. Department of Justice indicates that total violent crime grew at a slower rate than Florida’s overall population during Bush’s governorship.

While the population grew steadily, from 15.1 million people in 1999 to 18.3 million in 2007, the number of violent crimes committed in the state ebbed and flowed. In 1999, there were 129,044 total violent offenses. That number dipped to a low of 123,754 in 2004. And it grew to 129,602 in 2006, his last full year as governor.

That violent crime didn’t grow at the same rate as the population seems to corroborate the anecdotal evidence from South Florida’s top drug warriors—that, with time, the state became less bloody.

Raffanello said Bush’s efforts to improve communication between local sheriffs, the DEA, and other law enforcement arms were particularly fruitful.

As governor, he and his wife, Columba, participated in yearly Tallahassee summits that brought together the state’s drug warriors for networking, planning, and coordination. Raffanello said the impact of those meetings—and the impact of the governor’s involvement with them—made statewide enforcement efforts more organized and effective.

“I thought he really gave a shit,” Raffanello said. “It’s refreshing to see a politician care about an issue.”

So his efforts seem to have made Florida less violent and crazy, but Gamarra said the overall outcome was mixed. While drug-related violence went down, there weren’t great results as far as overall drug use.

“The objective of all of this stuff was to stop the flow of drugs into the United States,” he said. “And we have just as many drugs coming into the United States today as we did in 1985. And the price is cheaper and quality of the drugs is better.”

Still, Raffanello said Jeb’s greatest impact was the shift of drug violence from the Sunshine State to the U.S.-Mexico border, saying the violence in Florida decreased “exponentially.”

“We probably had three of the most successful years we had in the last two decades,” he said.