It was the summer of terror—an altogether different terror than the pandemic kind we’re living through now. But it was just as global and, at the time, just as harrowing.

This is what happened in the span of just two weeks in June 1985: a bomb went off in the international terminal of Frankfurt’s airport, killing three and injuring 74; a guerrilla group attacked a restaurant in San Salvador’s Zona Rosa, killing 12, among them three Americans; the next day, bombs went off across Nepal, killing at least eight people; three days later, an Air India 747 was bombed out of the sky over the Atlantic, killing all 329 people aboard; that same day, a bomb hidden in a suitcase went off at Tokyo’s Narita International Airport, killing two baggage handlers; in Spain on July 1, a bomb went off in the British Airways offices targeting TWA’s business operations on the floor above, killing a woman and injuring 27. Moments later, gunmen with submachine guns opened fire on the Alia Royal Jordanian Airlines offices 100 yards away, tossing inside three grenades that miraculously failed to explode.

And while all this was happening, during these very same two weeks, America barely noticed any of it as the country found itself in the grips of a hostage crisis that, thanks to new technology and an upstart cable network called CNN, was for the first time playing out 24 hours live on TV. Lebanese Shiite terrorists had hijacked a plane and were holding 40 Americans somewhere in war-torn Beirut’s Southern Suburbs. The TWA Hostage Crisis, as it came to be known, was an epic 17-day shitshow that whiplashed between abject terror and black comedy. It was America’s first reality show and it forever changed the media landscape and how we’re fed our news. As a young foreign correspondent for Newsweek, I got to see it all firsthand.

Let’s start with one iconographic fact: The picture that came to represent the entire ordeal, of a terrorist leaning out of the open cockpit window of the grounded TWA 727 holding a pistol to the head of pilot John L. Testrake—the very “Face Of Terror” shot that Newsweek and countless other magazines put on their covers—was staged.

The Terror

On the morning of June 14, 139 passengers passed through Athens International Airport security and boarded TWA Flight 847 en route to Rome, and then onto Boston, Los Angeles, terminating in San Diego. Twenty minutes into the short hop to Rome, two Lebanese Shiite terrorists rose from their seats brandishing weapons and ran up the aisle screaming that they were commandeering the plane. Hassan Izz-Al-Din, 22, and Mohammed Ali Hammadi, 21, had exploited a loophole in the airport’s already lax security by boarding from the transit lounge. With the flight’s final destination the United States, they knew the plane would be full of Americans. As they ran forward, Hammadi waved a 9 mm pistol while Izz-Al-Din held up multiple hand grenades with the pins removed. He held the pins in his mouth between his teeth.

Uli Derickson, the lead flight attendant, was putting on her apron and getting ready to serve champagne to the first class passengers when she heard a commotion and looked up. Izz-Al-Din charged up and karate-kicked her in the chest, sending her crashing against the cockpit door. He then kicked her again. She got to her feet and tried to speak to them. The terrorists, sweating and agitated, spoke no English but Derickson quickly ascertained that Hammadi spoke German—a language she was fluent in. This made her valuable to them as she could translate to the pilot. “We come to die, we come to die,” Hammadi informed her.

Two of the hijackers of TWA Boeing 727 holding sub-machines, inspect 19 June 1985 at Beirut airport the hijacked jetliner.

Nabil Ismail/AFP via GettyThe terrorists then kicked the cockpit door open and entered. Hammadi savagely pistol-whipped flight engineer Christian Zimmerman and first officer Philip Maresca and demanded the plane divert to Beirut. They then cleared the first class cabin, rearranged the seating in the back so the men were in window seats, women and children in the aisle and ordered Derickson to collect passports from the passengers. Hammadi then asked her to identify which passengers were Jewish. She told him she had no way of doing that. Hammadi went through the passports himself, identifying those he thought were Jewish based on their last names, and marched them to the front cabin, beating them as they went.

As the plane approached the Lebanese capital, the Beirut control tower refused to let it land. Airport officials turned off the landing strip lights and moved buses and blockades onto the runway. Testrake pleaded: “He has pulled a hand-grenade pin and he is ready to blow up the aircraft if he has to. We must, I repeat, we must land at Beirut. We must land at Beirut. No alternative.” After an agonizing 10 minutes, the Lebanese relented. The tarmac was cleared, the runway lights turned on and the plane touched down.

Now began negotiations to release some passengers in exchange for fuel. The terrorists had by this time come to trust and like Derickson—Izz-Al-Din would later, shockingly, ask her to marry him—and Derickson used her good graces with them to obtain the release of 17 women and two children. As soon as they slid down the emergency shoot, the plane was refueled. Derickson and Hammadi unhooked the yellow slide, letting it fall onto the tarmac, closed the hatch and the plane took off again.

I was just getting home to my apartment when the phone rang at 2:00 a.m. It was my bureau chief, Fred Coleman. I was the second man in Newsweek’s three-person Paris bureau, a job known as the “fireman” because you were often sent flying off on temporary assignment to places where there was gunfire. I was in my early twenties and if the job sounds wildly romantic, rest assured, it was. Flight 847 had landed in Algiers, had then taken off again and had just returned for a second time to Beirut. The hijackers were demanding the release of more than 700 mostly Lebanese Shiites who’d been swept up by the Israelis during their pullback from Southern Lebanon and were now being held in an Israeli prison. If the prisoners weren’t freed, the terrorists threatened to start executing passengers one by one. With so many Americans on board, the story quickly dominated the news cycle and Newsweek wanted to bolster the team already on the ground in Beirut.

By the time I got to Orly Airport at dawn that morning and met up with Newsweek photographer Peter Turnley, the plane had left Beirut for the second time. Where it was going, nobody had a clue. Turnley thought it was headed back to Algiers. Algeria had been the intermediary between Iran and the Unites States during the Iran hostage crisis of 1979 and was already playing a diplomatic role in this one. We looked up at the departure board—there was a flight leaving for Algiers in 20 minutes but there was only one seat left. Turnley somehow convinced the airline to allow him to sit in the jump seat. Never underestimate the wiles of a determined news photog.

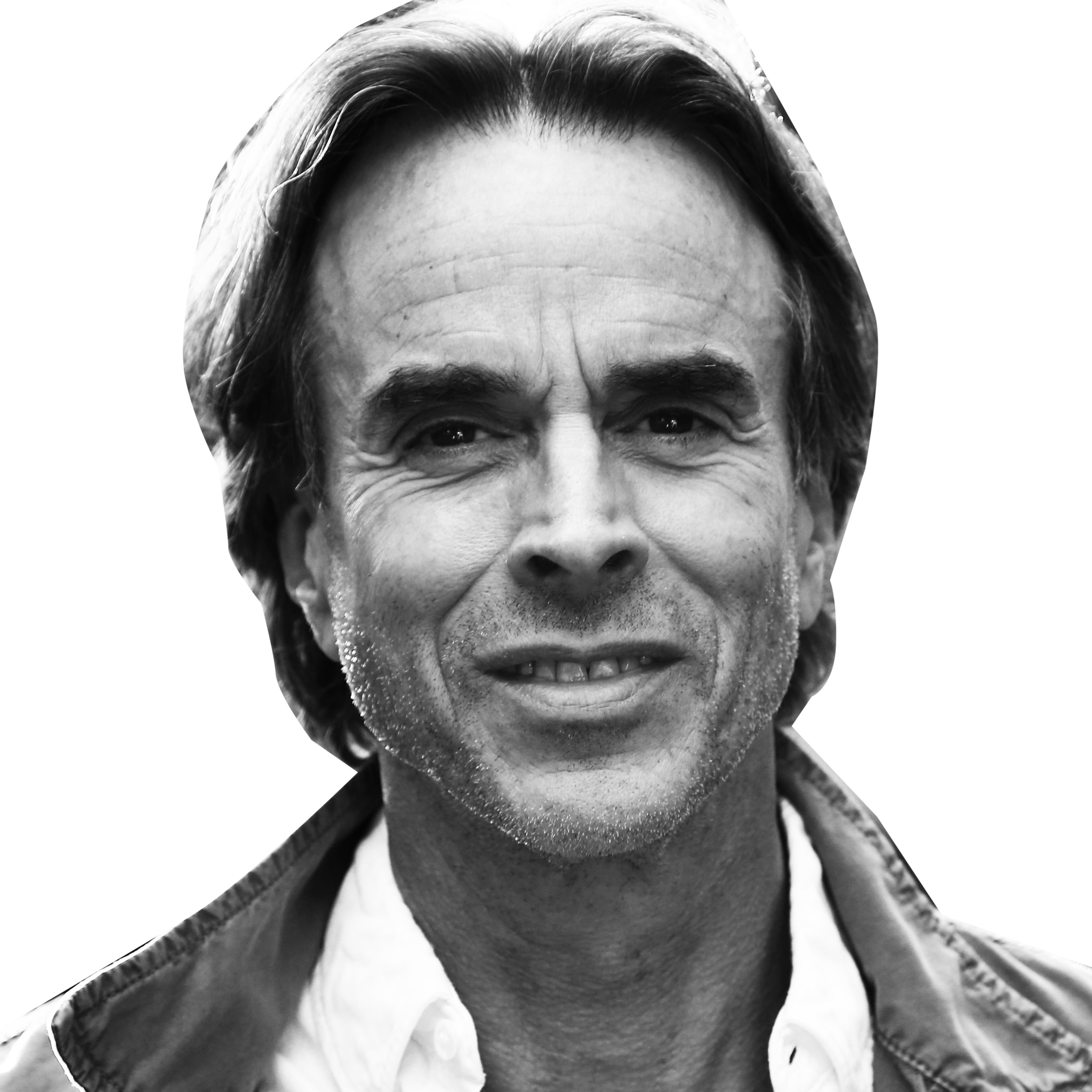

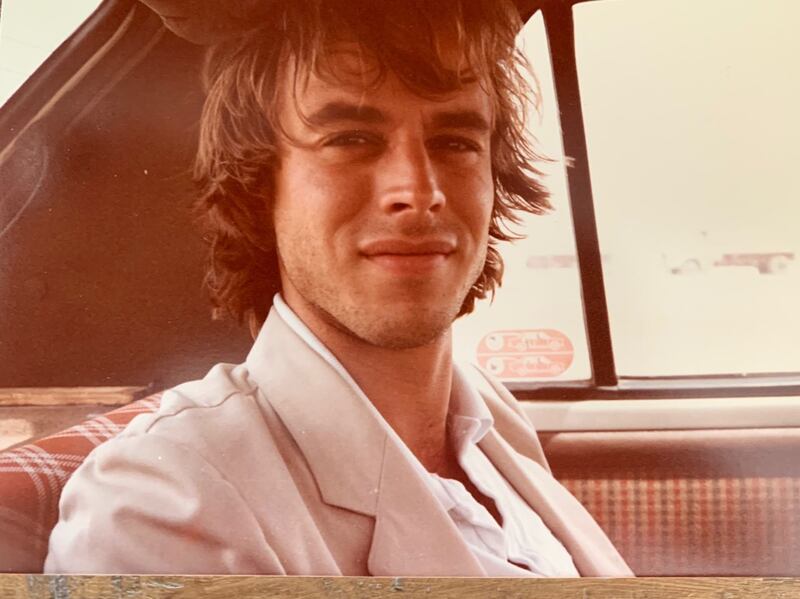

The author in the back of an Algerian cab after three days of no sleep, still in his Paris clubbing clothes.

Photo provided by Michael LernerWe landed in Algiers with no TWA plane in sight, feeling pretty stupid and wondering how we were going to explain this one away. Ten minutes later TWA Flight 847 landed on the tarmac. Algerian authorities immediately closed the airport and we suddenly found ourselves the only American journalists in sight on the biggest story of the year with no one else able to get in on it.

Meanwhile back on the plane, the terror had ramped up. While they were still in Beirut for the second time, the hijackers had identified three young American servicemen, Navy divers Robert Stethem, 23, and Clint Suggs, 29, and Army Reserve Major Kurt Carleson, 38, and were beating them bloody. “One was brought in with broken ribs and his hands tied so tight behind his back he couldn’t feel them anymore,” one passenger later told me. “They hit him over the head with the butt of a rifle and he had a lump the size of a fist.” Throughout the beatings to the servicemen and to other passengers, Derickson kept trying to intervene, repeatedly putting herself in harm’s way. “Don’t you hit that person,” another passenger later remembered her yelling at the hijackers. When one of the hijackers pulled a gun out on Suggs, Derickson jumped between them. Suggs later credited Derickson with saving his life.

She could not do the same for Robert Stethem. With circumstances on board in Beirut rapidly deteriorating, the hijackers demanded that members of the Lebanese Amal Shiite militia join them on the plane to stabilize the situation. Amal, more moderate than the Iran-funded Hezbollah to which the hijackers belonged, was headed by the charismatic Nabih Berri, and he wasn’t so keen. According to Testrake, that’s when the hijackers panicked. They grabbed the badly beaten Stethem, opened the plane’s forward hatch, stood him in the door and shot him in the head, dumping his body on the tarmac. They threatened to keep shooting passengers until Amal agreed to join them. Amal at that point relented and 10 of their militiamen boarded the plane, bolstering the original two hijackers. And then the plane took off again.

With the plane now back in Algiers for the second time, Derickson again took the lead. Ali Atwa, who was to have been the third hijacker, had been bumped off the plane in Athens because of overbooking and had made such a stink about it at the airline counter that Greek officials arrested him. They realized shortly thereafter that he was part of the hijacking squad. Now the hijackers wanted him freed and returned to them. Derickson implored the Amal militiamen on board to release more hostages and the rest of her crew in exchange. She had already used her own Shell credit card to refuel the plane with 6,000 gallons when the Algerians balked at doing so without payment for the fuel. When the Greeks agreed to release Atwa and flew him to Algiers, Derickson was released along with the rest of her crew and 53 additional hostages. She was uniformly credited by those released with having heroically saved many of their lives.

One of two heavily-armed Lebanese Shiite militants, his face hidden with a bag, who hijacked a TWA passenger Boeing 727 aircraft, looks out from the door of the jetliner on June 20, 1985 at Beirut airport.

Joel Robine/AFP via GettyI learned much of this from the released hostages themselves, whose bus I followed in a cab to their hotel in Algiers; many of them graciously agreed to answer my questions when I knocked on their doors so I could piece together their ordeal. When I asked what had happened to the passengers with Jewish-sounding last names who’d been marched to the front cabin, none of the freed passengers recalled seeing them again.

I returned to the airport. The plane was still on the ground and a TWA vice president had flown in to do what he could, which was not a hell of a lot. While interviewing him, I asked him about the passengers with the Jewish-sounding last names who’d been taken off the plane in Beirut. This, it should be noted, was a total bluff—I had no idea if they’d been taken off the plane. He looked at me, startled, and said: “How the fuck do you know about that?” Which meant that somewhere in Beirut a bunch of Americans were actively being held hostage and I was now the only member of the world’s press who knew that. I had just been given the biggest scoop of my very young career. By the time I got back to Algiers and located a functioning telex to file my copy to Newsweek, TWA Flight 847 with the remaining 37 hostages on board had once again taken flight back to Beirut.

At this point there wasn’t much to do in Algiers for the international press, which finally had been allowed to fly in, but to turn around and fly back out. I and most of the press booked tickets on a flight to Paris Orly with a connection on Middle East Airlines to Beirut. My direct competitor at Time magazine suggested we grab some lunch before the flight. An old Africa hand with a gut by now forged of steel, he suggested a small place he knew on the port that served bowls of lukewarm shrimp. As we returned to his hotel to gather our bags, I felt a rumbling. Ten minutes later I was exploding from every orifice. As I lay rolling on the floor of his room clutching my gut, I remember my rival promising to call a doctor and bidding me adieu until the next story, since I was obviously going to be missing the connecting flight to this one. He laughed and closed the door.

An hour later a doctor actually did show up. He gave me two massive, painful shots in each buttock cheek and a short time later, though still green and wobbly, I was once again able to walk without soiling myself. I made it to the airport—I’d of course missed the plane to Orly that connected to the MEA flight but there was another flight to Charles De Gaulle, which was located on the other side of Paris but, alas, had no Beirut connection. These were the days when the written press still had money and no one had more money than the news magazines. I landed at CDG, rented a helicopter, landed in Orly and made it onto the MEA flight to Beirut just as the gate was closing. The look on my rival’s face when he saw me come down the aisle in the same vomit-splattered clothes I’d been wearing for the last three days? Priceless.

The Farce

Now this is where the story turns weird. Shortly after TWA 847 landed in Beirut, the United States ordered the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Nimitz and the guided missile destroyer U.S.S.Kidd to positions off the Lebanese coast. A Delta Force team was reported to be on the way. Amal commandeered the airport and under cover of darkness moved most of the hostages off the plane, splitting them into small groups to discourage a rescue mission, stashing them throughout the Shiite neighborhood of Beirut known as the Southern Suburbs. Only the pilot, Testrake, and his immediate crew were left on board, guarded by four Amal militiamen. A powder keg atmosphere, right? You’d think Beirut would be locked down in crisis.

Think again. Of the many reasons reporters look upon Lebanon, like Vietnam before it, as the journalism story of its day, there’s one that’s undeniable: covering it was fun. “A beautiful city of unparalleled violence, decadence and deceit,” as the late, great foreign correspondent Christopher Dickey once called Beirut. With its Rubik’s Cube of shifting alliances that could generate endless copy and relatively press-friendly and geographically accessible warring factions, Lebanon was a war correspondent’s Disneyland. That was never more true than during a crisis when the world’s spotlight angled down upon it. So much American media swarmed in, spending so much money that Beirut turned into party town.

If the Iran hostage crisis of 1979 was the birth of terror as TV info-tainment, the TWA hostage crisis was its vulgar stepchild. With CNN, the new kid on the block, setting the benchmark with live 24-hour coverage, the three American TV networks were left scrambling to establish primacy amongst themselves. Fueled in part by panic over CNN’s round-the-clock prowess, the networks set about spending obscene amounts of money to convince themselves they were still relevant. “We have roughly 20 people in Beirut and another 20 here,” said CBS’s Peter Schweitzer, who had set up a base in a luxury seaside hotel in Larnaca, Cyprus. “We have two planes—a jet and a regular plane—that are constantly shuttling between Beirut and Larnaca.” ABC’s Pierre Salinger, whose expense account was almost as big as his ego, rented a huge seaside suite in Larnaca from where he would dub in his voice on interviews taking place in Beirut. I asked him if it was true that he had a special plane to fly in his beloved Montecristo cigars from Paris; he said it was not. They were Davidoffs. “It’s getting ridiculous. We’re all trying to out-do the other and we’re not thinking about the story. We’ve actually become part of the story,” said CBS’s Bill Redeker.

If the TWA hostage crisis turned into a media circus, Amal’s Nabih Berri was its wily ringmaster. Affable and fluent in English, he positioned himself as the main mediator in the ordeal—no small achievement since it was his own militiamen who were holding the hostages. Berri made the networks salivate, doling out exclusive interviews with groups of hostages like so much candy. First a press conference with five hostages, who implored President Ronald Reagan not to attempt a rescue mission. Then ABC scored an exclusive seaside lunch with three of the hostages. On and on it went. Berri wanted the release of his 766 people from Israel’s Atlit prison and he knew the best way to get that was to let American media do it for him.

Even the hostages themselves seemed to get in on the act. They nominated Allyn B. Conwell, 39, to be their spokesman. A tall, well-spoken Texas oil executive who spoke some Arabic and who’d lived in the Middle East for 10 years, Conwell took to his role with a bit too much panache. He became known as the hostage who wouldn’t clam up, opining on various matters Middle Eastern and appearing more like a network pundit than a hostage in peril. The media ate it up.

Not all the media, mind you. The written press was pretty much banished to the back lot as Berri understood the visceral power of images over print. So, too, did his militiamen, which leads me to that infamous “Face of Terror” cover photo of the hijacker leaning out of the TWA 727 cockpit window, holding a gun to Captain John Testrake’s head. According to Testrake, who was later interviewed by CNN’s Jim Clancy, the photo was really a picture of media manipulation. The gunman wasn’t in fact one of the hijackers but a teenage guard who saw a news crew on the tarmac approaching the plane and, with it, his chance for 15 minutes of fame. He asked Testrake to stage the photo. When Testrake balked, the kid unloaded his gun and handed it to Testrake to verify it was empty. According to Testrake, it was only because the kid was becoming unhinged at the thought of missing his moment that Testrake agreed.

In the end, the hostages were all released unharmed. As a result of secret negotiations between Iran, Israel and Syria, Israel did quietly release the 766 prisoners it was holding. In keeping with the quasi-comedy of the final chapter, the hostages were sent off with a lavish farewell banquet at Beirut’s seaside Summerland Hotel that was co-hosted by Amal and ABC, which had gotten most of the scoops. Some of the hostages apparently drove themselves to the event.

An American hostage flashes the V-sign for victory after her release by the hijackers of the American TWA Boeing, as she arrives at Houari Boumedienne airport in Algiers on June 15, 1985.

AFP PHOTO/PHILIPPE BOUCHON/GETTY / GettyAs to the hijackers, Mohammed Ali Hammadi was arrested in West Germany in 1987 and was charged with the murder of Navy diver Robert Stethem. He served 18 years and was paroled in 2005. The United States considers him a fugitive from justice and he is on the FBI’s Most Wanted terrorist list. Hassan Izz-Al-Din was never arrested and also remains on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. Both he and Ali Atwa, who also was never captured, are believed to be living in Lebanon.

Uli Derickson returned to her family in New Jersey, relocated with them to Arizona, and a few months after that resumed flying for TWA. She later worked Delta’s international routes. She died of cancer at 60 in 2005.

Nabih Berri survived that summer of terror and the next two years of more of the same. In 1992, he became speaker of the Lebanese Parliament, a job he still holds today. If there is an irony here, though, it is this one: Looking back at the violence and terror of those years, a time before 9/11, before ISIS learned to manipulate the media in a far more gruesome way, before an area the size of Connecticut was on fire in the western United States, before the middle of a pandemic that will have killed more than 230,000 Americans by the end of this month, before an American president tried to subvert a national election and threatened to hold onto power by force, it’s hard not to feel those days were so much less threatening.