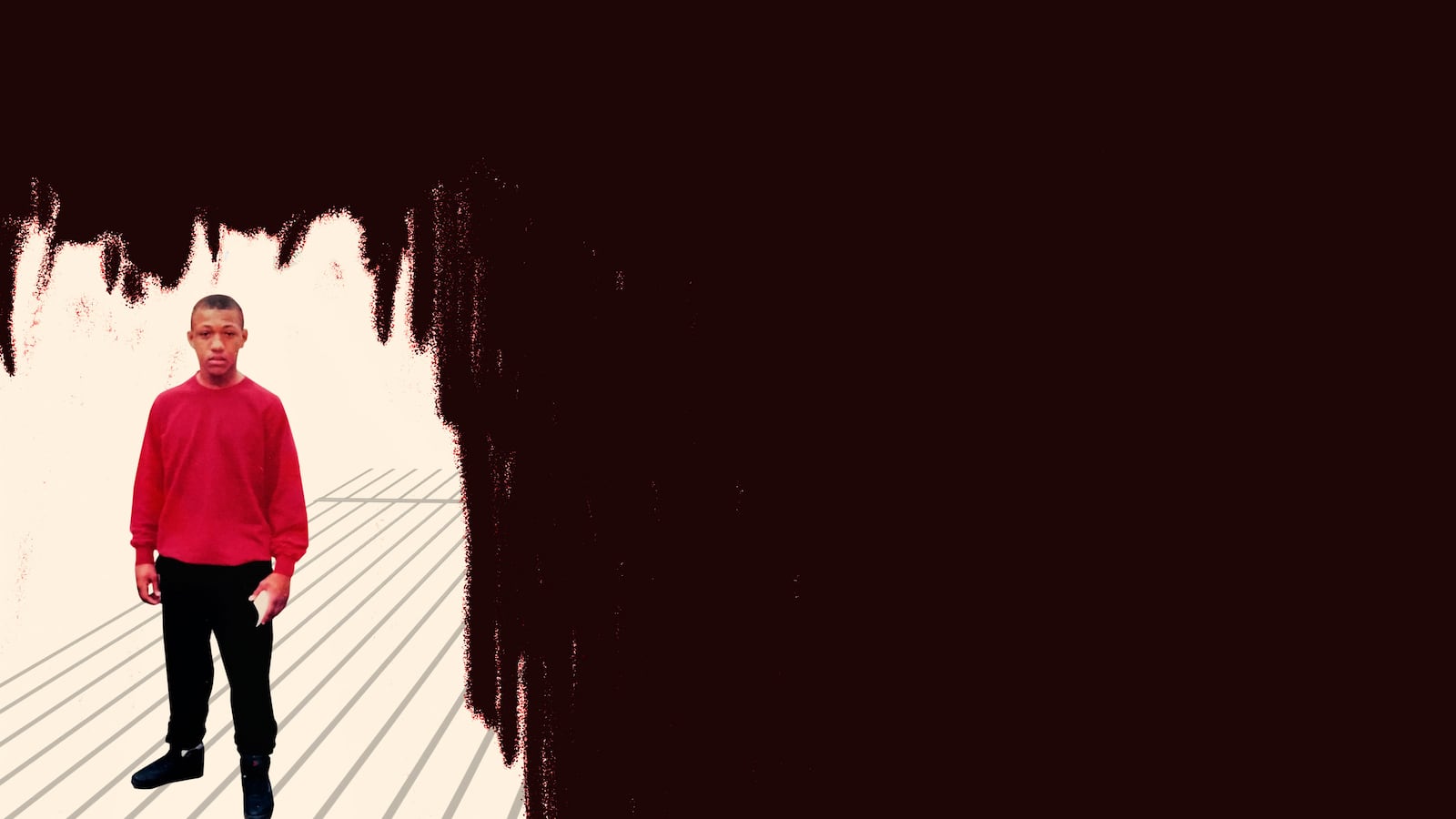

You’ve heard my story before, or something like it. You’ve seen it on TV or in a movie: A lost kid, a life forever altered by a first encounter with our nation’s criminal justice system. It happens far too often, to far too many lost boys in America. It’s a narrative we must change.

As a young Black kid growing up in Washington, D.C., I hoped to become a lawyer one day. I wanted to be like Perry Mason, a heroic figure protecting the falsely accused. I told my grandmother, who largely raised me, that this was my plan.

But my first encounter with the criminal justice system pushed me in a different direction, along a path that ultimately stripped me of those dreams. Here’s how.

My formal education ended with my graduation from sixth grade, an academic cul-de-sac common in my childhood neighborhood. It was a neighborhood filled with drugs, drug users, drug selling, violence, police raids, police brutality, and police killings—a community that had never fully recovered after being ravaged by the riots of 1968. It was my entire world, and as I aged it became harder and harder to imagine experiencing life anywhere other than on those streets.

My trajectory was sadly typical. My dad went to prison when I was 8. He had abused me physically, but like many children of abusive parents, I was so lonely without him in my life that I mourned his absence, and his incarceration punched a huge hole in my heart. My mother was not in the picture at that point, so my grandmother was left to raise me.

She was the rock in my life, but her deteriorating physical and mental health left me lonely, gripped by a sense of isolation. We may act otherwise, but every 12-year-old boy yearns for parental guidance. When I realized that would not be coming my way, I tried to take control of my life and left.

Away from home, I felt free. It was an exciting time for me, running around Washington with people whose lives were just as shapeless as mine. The streets seemed fun, exhilarating, a place where anything seemed possible. At an early age, my father and uncle had introduced me to the “family business”—selling drugs—and so it went for me. I was making some money, and in some respects, this life transition gave me a sense of security. Peers on the street and drug middlemen became my family, my security blanket.

But of course it was all a myth, a sad and shaky substitute for the support I really needed.

One day in April 1988, when I was hanging out at the playground at 9th and Westminster streets, in Northwest D.C., two white men in a Volkswagen Rabbit pulled up and asked for “two for $35,” drug slang for two $20 cocaine rocks for $35. I made the transaction, they drove away and I went back to sitting on the playground talking with friends. To me, 13 at the time, it felt like just another drug sale, just another ordinary day in “Wild Wild Westminster,” a name we coined for the neighborhood based on Kool Moe Dee’s song “Wild Wild West”. Nothing seemed off. I was in my element, living on the street and feeling safe.

Minutes later, a pair of plainclothes officers from the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department pulled up, moving fast. They came straight at me, asked my name and demanded to know whether I had any drugs on me. I replied no, which was true at that particular moment. In my young mind, I assumed their intent was just to harass me and my friends for hanging around outside. That would have been normal, because it happened all the time.

But then another squad car pulled up, with the two men from the Volkswagen Rabbit. In an instant I realized this episode was anything but normal. The men—officers posing as customers—were ready to I.D. me as the kid who sold them drugs.

Before long I was handcuffed and sitting in the back of their police car, as the officers searched the area for drugs. They found two packages of rock cocaine in some overgrown weeds beside an apartment building—old bags, filled with dirt and mud. They weren’t mine, but it didn’t matter. That’s all it took to process the arrest.

It is well known that during this period in D.C., police were targeting Black communities as part of the War on Drugs. This strategy was common in other cities as well, and it fueled severe racial disparities in our criminal justice system, including higher rates of police stops, searches, arrests and convictions for Black people, and harsher prison sentences as well.

I was just another young Black boy, AWOL from his home, about to be sucked into a system that chewed up kids who looked like me every single day.

They took me to the police station, searched me again, and found nothing. They locked me in a holding cell and performed a traumatic invasive strip and cavity search—still nothing. Through it all, I fought to stay calm, but felt overwhelmed by a creeping sense of dread.

As I waited, emotions swept over me in waves. There was anger, frustration, shame. I felt violated, trapped, disgusted and intensely lonely.

This was my first offense and, aside from the usual harassment every street kid absorbed from beat cops, I had not had many prior dealings with men in blue. The lone exception was a positive one, the visits I had made to the Metropolitan Police Boys and Girls Club. Interacting with police at the club, I came to respect the officers, who seemed committed to providing guidance to kids lacking positive role models. But my arrest changed all that, leaving me resentful of police instead.

I did not fully comprehend it at the time, but my first encounter with the law had a devastating impact on how I saw the world and my place in it in the years ahead.

Eventually, I was sentenced to juvenile probation for the drug offense and released to the custody of my mother, who had managed to establish a safe home for herself after years on the streets. But instead of letting us make a go of it as mother and son, my probation officer recommended that I be moved to an out-of-home placement, concluding that it was the best environment for me to receive education and vocational training. I was yanked from my mother’s home and placed in secure detention in the Receiving Home for Children, now known as the District’s Youth Services Center.

As I sat in the holding cell at the receiving home, the tears flowed. What was happening to my life? Confused and filled with self-doubt, my head swirled with thoughts of my father in prison, my grandmother’s failing health, and the mother and siblings I could no longer see. The system had uprooted me but offered no support or services in return.

Eventually, I was sent to the Rosa Parks Youth Shelter Home, a place where fights broke out nightly as kids sought to showcase their toughness. I stayed there a few nights, but I missed my family, friends and life so much that I decided to run away, returning to my mother’s house. I was a child— confused, afraid and unable to understand why I had been taken from my home. I could feel my life turning upside down, and felt helpless to stop it.

My mom and stepdad told me that fleeing the Shelter Home was wrong and that I had to return. As I appeared in court with my mom, knowing that I would no longer be living with her, I felt devastated. Next came an interview with a staff psychiatrist from D.C.’s Youth Services Administration, who concluded that a more structured setting would be best to help channel my “aggressive tendencies” into socially acceptable behavior. I was confined at the receiving home for a time, but my ultimate destination was set: residential placement.

As I awaited my transfer, the abnormality of incarceration slowly began to feel normal, proving how the human mind can adapt to the most challenging situations. In retrospect, I know my adjustment was an effort to bury the trauma of being separated from my support system—my mother, siblings, friends, and other family members. This first encounter shaped my perspective of the criminal justice system, but it also shaped my vision of myself. Gone were the dreams I had for my future. I was only 13 years old and yet, after one arrest, I had already come to view incarceration as a normal, acceptable fate. Years later, when I was charged and sentenced in the adult system, the transition was easy. I knew what to expect.

After six months in the receiving home, instead of a residential placement my judge returned me to the custody of my mother, because she was tired of holding me while the government tried to placed me in residential placement. I was on probation for a year and stayed out of trouble. My probation officer scared me so bad when he told me that every other Wednesday I had to be sitting in the seat I was in by 4 p.m. I said to him “school don’t let out until 3 p.m. and the bus could be running late.” He said, “that’s your problem, because if you are not in that seat you are going back to the receiving home.”

My experience illustrates how the criminal justice system destroys lives, by dehumanizing people and persuading them that they are less than, that they do not deserve more. While I understand now that I was simply coping with extreme trauma the best I could, convincing myself that a life of confinement was not that bad was the worst mistake I had made in my young life. Instead of correcting my life’s course, the system was propelling me down a dire path.

I grew up wondering why many of the positive role models in my life did not have time for me, and why they could not see that I wanted and needed more. My uncle did home improvement work. As a kid, I desperately wanted to go on jobs with him, to help. But I guess he figured I was too small to be of any use. Other work options in the neighborhood were scarce, except for those that provided me a doorway into selling drugs. As my youth slipped away, becoming Perry Mason began to feel more and more like an impossible goal.

It’s not uncommon for young people growing up in similar situations to lack family support to help them chase their dreams. Ideally, the community and social support systems—a teacher, a counselor, a preacher, a coach—can fill that void, and help a confused kid when he’s lost and begins to veer off track. But such actors weren’t materializing in my life. And unfortunately, my first encounter with the system led not to help, but to six months in the receiving home, separation from my family and relocation to an unknown, scary place and one year of probation. There were no programs, no encouragement, no supportive mechanisms to ease my trauma and guide me forward.

Questions linger in my mind to this day. Why was the system’s first and only response to put a 13-year-old boy in a cell? The government knew about my parents’ criminal past, so why not proceed with caution, provide some support and help me avoid traveling toward the same, awful destination? I was clearly struggling, so why was the only response to arrest, charge and incarcerate? Had the system been kinder and gentler to that Black boy, I believe things would have turned out differently. Instead, I was headed for complete darkness.

Yes, my first encounter with the justice system was not my last. Sadly, that drug arrest at 13, with six months served and one year of probation, did not help me turn my life around or walk the “straight and narrow.” Instead, it stole away what was left of my childhood and drove me further into the embrace of the streets.

At 19, I was arrested for the murder of a woman and attempted murder of a man, crimes committed when I was 17. I committed my crimes hours after I identified my 17-year-old cousin in the morgue, lifeless, just like so many Black boys growing up with trauma, living in fear, peer pressure, and poor decision-making. I take full responsibility for those unconscionable acts and have dealt with remorse every day since.

I spent nearly a quarter-century behind bars for my crimes.

It took me years in prison to find the real me, and it would not have been possible without another pivotal first encounter, this time with another man in prison who would become a mentor. Lucius F. McCoy-Bey, Sr., an older, incarcerated man helped me forge a new path, one that built my self-worth and helped me address my self-doubt. Eventually, I received a resentencing by the court and returned home on Dec. 4, 2018.

Inspired by Lucius, I have dedicated myself to the practice of mentorship, trying to provide helpful guidance to others. I began this work while incarcerated, and continue it in the community today. I was proud to recently co-author a report (PDF) on the Young Men Emerging Unit in the DC Jail. Mentoring youth and young adults means the world to me. Providing young people with the wisdom of life experience can help them cope with the trauma caused by growing up in neighborhoods and families like mine. And building their confidence by ensuring they recognize their unique gifts and talents can help them overcome hardships and grow.

Mentoring gave me my life back. I can only pay it forward to save the next me, by giving some other 13-year-old boy a comforting hand on the shoulder, and the small miracle of hope. But it takes more than that to overcome the tragedy of so many lost boys left to be broken into pieces by America’s criminal justice system.

It takes a lot more. But it’s worth it, I swear.