I couldn’t stop reading the story The New York Times broke this week, that Leroy “Nicky” Barnes, the “Mr. Untouchable” of Heroin Dealers, Is Dead at 78.

Has been dead in fact since 2012, but because of his participation in the Federal Witness Protection Program, that information had been suppressed. I wondered about the timing of the announcement, confirmed by one of his daughters and one of his old prosecutors. Was it a response to the news a week earlier of the death of Frank Lucas, his one-time rival in the Harlem heroin trade?

Many who lived through the chemical tyranny of the ’70s might say: Who cares? Ding-dong, the sorcerer is dead; Nicky’s life and the black magic of deadly white powder evaporated into the aphotic shadows of time’s abyss.

[VIDEO: Mark Jacobson interviews Barnes and Lucas]

Whatever the reason, the delay seemed fitting and “shadow” the operative word for me here. The shadow of Nicky Barnes has flitted across my life over the better part of four decades. As a young Harlemite, I heard about him, but never actually saw him. I was in pursuit of a ghost, and his rides:

Was that Nicky’s Corniche that just glided past Smalls Paradise? Yo, is that Nicky’s Jensen Interceptor parked in front of Thelma’s Bar on 148th and Seventh? That money-green BMW Bavaria—that joint with the headrests in the back seat—that’s Nicky’s car? Right?

I can remember after shooting hoops on the courts of Col. Charles Young Park on 145th and Lenox, standing for what seemed like hours across the street from the garage he owned—Harlem Rivers Motors Garage—trying to get a glimpse of him, but the specter never materialized.

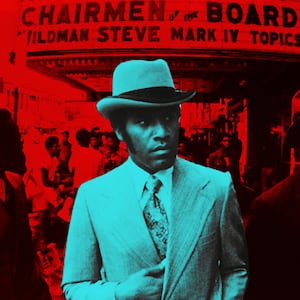

When I finally saw Barnes, it was not in the flesh but on the cover of the New York Times Magazine! A few of my friends in Esplanade Gardens gathered on the bench near the bust of Dr. Martin Luther King at the top of the hill on 147th Street, enthralled by the image of Nicky Barnes on the cover. A black man from Harlem—one of our own!

Barnes was a role model to myself and a lot of the young black men I grew up with in Harlem. The murders of Malcolm X/El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz and Dr. Martin Luther King left a vacuum. As far as strong African-American men that I revered, my dad (GOD rest his soul) was my ultimate hero.

However, Nicky Barnes seemed to be someone who white society both feared and admired. Even his name—“Le Roi”—is French for “The King.” As Harlem royalty, he was the original Dapper Don, who not only drove sleek foreign automobiles, but adorned himself in fitted suits by Brioni and Yves Saint Laurent, shoes by Gucci and Vittorio Ricci, and eyewear by Cazal and Playboy. Nicky paid off dirty cops, hired heat-seeking defense lawyers to outmaneuver the judicial system, and—according to that Times profile—inspired pop folk legend Jim Croce’s outlaw ode, “Bad Bad Leroy Brown.”

Barnes was also the catalyst to my career as a screenwriter. He is the template for “Nino Brown,” the monstrously ruthless crack czar of the 1991 Warner Bros. film New Jack City. The name for the character was an inside salute to the dope boys I grew up with, and the swank brown shopping bag for Nino Gabriele, a chic men’s shoe boutique on the Upper East Side. In 1988, I was hired by film producer Rudy Langlais—who was also my editor at The Village Voice and Spin magazine—and the late George Jackson to rewrite Thomas Lee Wright’s screenplay “Nicky,” based on the life of Nicky Barnes. That was supposed to star Eddie Murphy as Barnes, but studio head Frank Mancuso, Jr. nixed that idea. The script went into turnaround, and was picked up by the legendary musical icons Quincy Jones and Clarence Avant, and their Grio Films at Warner Bros.

Because of my reporting on the crack epidemic that was devouring Harlem, and had spread across the country, I wanted to flip the scrip (pun intended) and change the metabolism from heroin to cocaine, and cocaine into crack. Nino Brown was Nicky Barnes dressed like Teddy Riley and Bobby Brown, and his CMB (Cash Money Boys) narcotics consortium was Barnes’s “The Council” mixed in with Detroit-based ’80s super-cartel YBI (Young Boys Incorporated). It took a year and six drafts to make Nicky into Nino.

Over that year writing New Jack City, I had to come to grips with my complicated admiration for Barnes, a sort of cultural Stockholm syndrome. As I crafted the abhorrent Nino Brown—the same suave and charismatic creature who gave out turkeys to the poor on Thanksgiving, and used a young girl at a wedding as his shield against gunfire during a shootout—I realized that Nicky Barnes was a poster child for Narcissistic Personality Disorder. He twirled in the nebulous and ego-centrifical force of an untethered lack of conscience.

My mind hearkened back to the days of riding the M7 Bus from Hughes High School near the West Village, and the turn that the bus made on 116th St. and Manhattan Avenue. That strip between Eighth Avenue and Manhattan Avenue looked like the Carnival of Lost Black Souls. In the early ’70s, Harlem’s center was not holding, exemplified by the teaming swarm of heroin addicts looking for, as I always heard Curtis sing it, “Two bags please, for my generous needs.” An army of the ensorcelled that slouched to the grotesque Bethlehem of the Royal Flush hotel, attempting to set sail on vessels of nickel and dime bags, to the golden shores of their illusive Byzantium. In reality, their paradise was a populous of semi-comatose folks with abscessed and balloon-sized hands in gravity-defying nods on street corners. This was no heaven and Nicky Barnes was no savior. He was a Hermes-adorned magus who reclined on an Eames lounge chair in a Hudson River high-rise, deaf to the wailing and bewitched hordes on 116th Street.

Nicky—like Nino Brown, effectively portrayed by Wesley Snipes—also used his get-out-of-jail-free-card by snitching on not only his crew (and his wife Thelma Grant), but serving as a cooperating witness in 50 murder and drug cases, involving 109 people. These were RICO cases that were handled by-then U.S. Attorney Rudy Giuliani, who’s claimed contested credit for using the racketeering law this way. Barnes felt that his snitching deserved to be rewarded, so he lobbied for a presidential pardon. The person championing Nicky’s appeal? None other than Rudy Giuliani.

“I think he should be given credit, for his having cooperated with the Government,” said Giuliani during that time, “To encourage others to come forward and cooperate and bust up these operations. In my view, he should be permitted to be released from prison.”

After being transferred to a minimum security facility, Barnes was released from prison in 1998, and placed in the Witness Protection Program.

All of these things factored into my reassessment of my youthful hero worship for Barnes. I even wonder if Nicky is responsible for all of the gentrification in Harlem, because of how he—and many other “legendary” Harlem drug dealers—caused the property value to be cheapened so drastically, via the systematic destruction of Harlem’s vital real estate. I don’t know.

And I can’t ask Nicky Barnes about any of that, because he is gone. All the way gone for the last few years, it turns out. With a life of shadows in witness protection—a new name, a new identity—for decades before that. Some folks over the past 20 years think they have seen Nicky Barnes.

Maybe. Maybe not. You never know. That’s how ghosts get down.