If there is one person who embodies the full velocity of Britain’s cultural insurrection and its raging libidos in the 1960s, it has to be David Bailey.

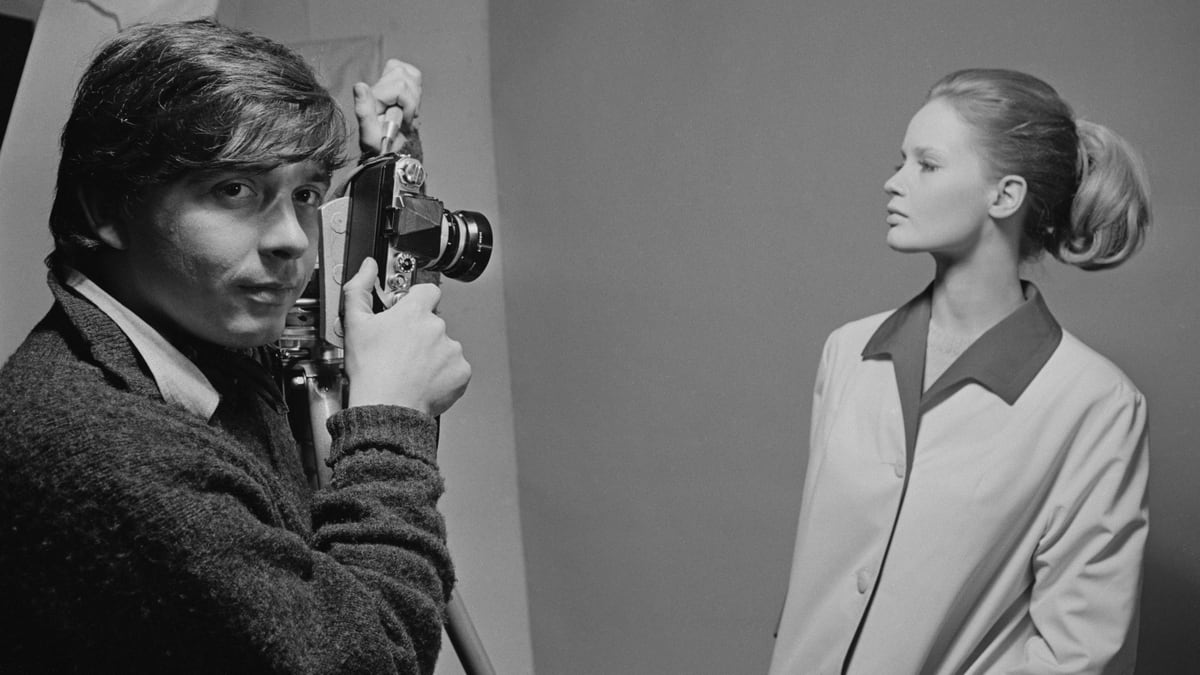

Through his camera lens and his life, Bailey gave face and voice to a generation that celebrated bold expressions of sexuality—blowing up stereotypes of British straitlacedness.

Bailey talks candidly about his sex life in his new autobiography, Look Again.

Of course, the #MeToo searchlight has fallen on some dark corners in the history of fashion photography, with stories of models subjected to casting-couch coercion and a sense that a lot has been covered up.

Bailey claims he was never a predator. In an interview with The Guardian last year he said: “If you wanted someone for the cover of Vogue, she had to be good. Not at fucking. She had to be good at modeling.” In his book he says of the women he photographed: “I don’t say I slept with them like it’s a conquest; it’s just what happens if you’re close to somebody.”

I wanted to check that typical touch of braggadocio with a woman with a rare knowledge of Bailey’s generation of London photographers and the milieu in which they worked—as it was when they swept all before them, so I sought out Suzanne Hodgart, a legendary photo editor. She confirmed Bailey’s account: “His affairs were a by-product of his work. The girls didn’t have to sleep with him, it wasn’t a transaction. There wasn’t a casting couch.”

Bailey’s first embraces often happened not in the flesh but through the camera lens.

Anyone who meets Bailey is instantly aware of his laser-like eyes, and when the camera becomes their accomplice the effect on the sitter can be mesmerizing. As Bailey says: “I fall in love with people when I photograph them for that 15 minutes or half-hour; they become the whole center of the universe.”

The first big crush of Bailey’s life was Jean Shrimpton, a model as emblematic of London in the 1960s as Bailey himself.

The pairing of Bailey and Shrimpton began with a shoot for British Vogue in 1961. A year later she was on the cover of the first issue of the London Sunday Times magazine, where I was deputy editor. The editor was Mark Boxer, who with that first issue spotted and defined the nascent zeitgeist of Swinging London. (Bailey credits Boxer as his most important mentor.)

Shrimpton was an exquisite and tantalizing avatar of a new kind of English beauty—classy and well-bred but also subtly erotic, with amazing legs and an unblinking and lubricious intimacy with the camera. Bailey says: “I was photographing women the way I saw them on the streets. People could identify with Jean because I didn’t make her look like a stuffed shop mannequin. Suddenly she was someone you could touch, or maybe even take to bed.”

When Bailey tried to do just that with Shrimpton he was rebuffed—at first.

At the same time, Shrimpton’s sister Chrissie was dating a teenager named Mick Jagger, as yet unknown. Bailey was in a failing marriage. Shrimpton’s father threatened to shoot him if he seduced his daughter, which he did after three months of trying. As Bailey says, it was a parenting nightmare: one daughter being pursued by him and the other by Jagger.

Bailey and Shrimpton never married but they were together for two and a half years. The break-up came, according to Bailey, “because Jean became more important than me.”

She moved on, to Terence Stamp, who had just become a star for his performance in the movie Billy Budd.

Shrimpton wounded Bailey: “That’s the only time it’s happened, allowing a woman to break my fucking heart. Wasn’t going to happen again. It made me much tougher.”

Just how strong that feeling for Shrimpton remains was apparent to me when I met Bailey last year as he was working on the book.

“It wasn’t very swinging if you were a coal miner in Yorkshire. It was swinging for about 2,000 people in London.”

Bailey has been a workaholic all his life. He operates in London from a buzzing atelier on the edge of Bloomsbury—it’s actually a converted cottage in a quiet mews that feels like an artisanal workshop, with plain and somewhat worn furnishings. Even on a grey morning, as this was, there was a lot of natural light from east-facing windows, the kind of natural London lighting that Bailey likes to use in his portraits.

I thought we might indulge some shared nostalgia about the Swinging Sixties. I was swiftly corrected: “It wasn’t very swinging if you were a coal miner in Yorkshire. It was swinging for about 2,000 people in London.”

From my own experience I would say that that number was a serious underestimate, but I took the basic point: there was a lot of poverty, squalor, and racism in the London of the 1960s.

Bailey was giving me the eye, sizing me up. Someone had warned me that he could be a grumpy old man. He was 82 and his looks were well seasoned like the timbers of a sailing ship, but he was not grumpy. In fact, he seemed happy to find himself being interviewed by somebody older than himself.

He introduced me to his wife, Catherine Dyer, who had arrived with their dog, a large chow-chow named Mortimer: “This is Clive. I like him. He’s an old fucker, older than me.”

“That’s made his day,” said Barbara Seymour, his personal assistant.

Bailey’s portrait of Shrimpton in her ravishing prime hung prominently behind us. He followed my gaze.

“The most beautiful girl I had ever seen” he said, as though reliving the moment. “Still is.”

The quality that Bailey unlocked in Shrimpton, a new kind of street savvy classlessness, was subversive. Until then British models were sought after because they were thought to be posh, even a bit snooty as they looked down their long noses at the camera.

I brought up this question of class. Bailey himself arrived on the scene from London’s East End as a working-class grenade tossed into the bourgeois salons of 1950s British fashion photography.

Did he feel like an outsider then?

“At first I worked in a studio with (the photographer) John French, that was with four gays and a Jew. We were all outsiders. That’s how I fitted in.

“When I started working for Vogue they made it very fucking clear that I was different. ‘Oh, isn’t he sweet, I love your accent.’ They tapped me on the head, as though I was a toy.”

He wanted to use Paulene Stone, a young and beautiful working class model but Beatrix Miller, the then-editor of British Vogue, didn’t approve of her accent.

“I said, I’m not photographing a fucking accent, but she wouldn’t use her. That’s why Paulene never quite made it.” (Stone had a successful later career as an actress).

As Bailey made it himself he broke away from fashion and became the portraitist of choice for the exploding talents of the time—Michael Caine, Mick Jagger, Peter Sellers. He also moved up in society, recognized for his talent and enjoyed for his wild boy reputation.

One of his new admirers was Princess Margaret.

“I liked her. She used to play that game, wanting to be one of the boys and then suddenly wanting to be Princess Margaret. She never played that game with me. Tony Snowdon (Margaret’s husband from 1960 to 1978) resented me in a way, because she sent me letters congratulating me on my work and he said, ‘she never sends me a letter.’ After they broke up she carried on being nice to me. I smoked a joint with her once.”

There was another enduring complaint about Lord Snowdon. Bailey produced a box set of his portraits, The Box of Pin-Ups, that included one of Snowdon. Another was of the notorious psychopathic gangsters from the East End, the Kray twins.

Snowdon objected strongly to being included with them, and when Bailey proposed an American edition it was sabotaged by Snowdon, who denied permission for his portrait to be used. To this day, Bailey’s nickname for Tony is “Snowjob.”

I asked Bailey what he thought of Tony as a photographer.

“Not much.”

“If the dog died I’d be very upset. I’d be more upset about that than my dad.”

Bailey’s opinions can be brutal. In his book he is savage about his father, a womanizer who showed little interest in his son until he became famous.

In 1968 he suddenly reappeared—“gaunt and ill, and like some figure out of Dickens.” Bailey gave him some money. Later it turned out that he had cancer, and Bailey paid for him to be treated in the London Clinic, an expensive private hospital, where he died.

“Was I upset?” Bailey writes. “It’s upsetting if anyone dies. If the dog died I’d be very upset. I’d be more upset about that than my dad. I never liked the cunt anyway. Horrible bloke.”

He seems fonder of his mother Gladys. She was descended from Huguenot weavers who moved into the East End in the 18th century. She was the only bookish member of the family and, by his account, a strong character with a forcefield like his own.

Bailey’s wives and lovers had to accommodate his eccentricities, as they encountered them on moving into his homes.

Catherine Deneuve, for example, fell for him at the end of a photo session for a spread in Playboy.

Talking to Bailey’s ghost writer, the journalist James Fox, Deneuve said, “I was attracted to Bailey. To me he was not like an Englishman in the way he talked and moved and the way he did things—he was always very passionate and enthusiastic.”

This was in 1965. Little more than two months later they married. When she moved into Bailey’s house in London she discovered that she was sharing it with 60 parrots that were living, uncaged, in the basement, and had a habit of moving upstairs. (The metaphor is tempting: releasing strong spirits from conventional constraints, i.e. Bailey from the constraints of class.)

“They were the residents” says Deneuve. “I was definitely the guest… it was not a very long marriage but it was a very nice relationship. Nothing was complicated.”

In 1967 Bailey met Penelope Tree, the striking young daughter of a rich Anglo-American couple: “In looks and style she was ahead of everyone, a complete original. She was like a mixture of an Egyptian Jiminy Cricket and Bambi. Her legs went up to her neck.”

She was 17. Other photographers had already taken portraits of her—Diane Arbus and Richard Avedon.

Bailey concedes that Avedon’s shots of her were the best ever taken “much better than mine.”

This puzzled Bailey. Avedon, he says, thought there was no sex in photography. “I think photography is all sex. He never fucked anyone, Avedon, I think he was non-sexual. I was with three girls he really liked, including Penelope, and I’d slept with all of them.”

He didn’t sleep with Tree until 1968, when she was 18, on a shoot in Paris, and then she went to London to live with him for six years.

Fifty years later she told Fox that in the living room she found a centerpiece that looked like a shrine: “…photographs of all his past girlfriends, all in little gold frames, all the same size. It was like notching up kills on the side of Air Force planes.”

When Fox and Bailey began looking up Bailey’s old lovers and wives it was obvious that eventually they would have to seek out Shrimpton. Bailey and Shrimpton had not met for years, and she had long been happily married.

They went to her home and retreat, a clapboard house in remote Cornwall.

Shrimpton said she hated being famous. She joshed him: “Why are you writing this book? Is it because you want to stay famous?”

Bailey gave an unconvincing denial. There was more mutual teasing, until they found familiar ground in their memories of their golden youth.

“I was young then” said Bailey. “It’s nice seeing you. It’s funny, if you hadn’t fucked off and left me for Terence Stamp we’d still be together.”

“No, we wouldn’t be,” Shrimpton said, firmly.

“No, we wouldn’t but we might have been,” said Bailey.

“In your dreams,” she replied.

Bailey married Catherine Dyer in 1981, when she was 20. They met when she was modeling for a shoot for Italian Vogue. It turned out that she had gone to the same finishing school as Shrimpton.

“I think her parents thought she was a nice girl—until we got together, and then she was a naughty girl. They were horrified.”

He recalls: “I could see some things in her, like I saw in Jean, that nobody else did. It was always the same thing. It’s always the intelligent ones that are good.”

They have three children and I thought they looked very content and grounded together. Had he finally become a family man, I wondered?

In his book Bailey is straightforward about his domestic life, or lack thereof as he works without stint: “My basic attitude to children and to marriage is that it’s nothing to do with me. It’s something other people want to do… I’ve never really wanted children… a pram in the hallway is the end of creativity.”