It took me about a month after lockdown began in March to get my bearings, to really understand, that is, what the new COVID-19 reality was going to look like for a long time: basically stuck in a cultural deprivation tank for… ever.

At first I joked with friends and co-workers that I could handle quarantine better than a lot of people, since I’m already half a hermit anyway, don’t watch much sports, don’t go to bars, and can pretty much take or leave going out to eat. I would miss live music and going to the movies, and I would miss colleagues and friends, but other than that I thought I would be OK.

I was not entirely wrong, although good lord this pandemic, like everything about this year, does drag on. Who would’ve thought before 2020 that bingeing The West Wing would be considered a form of self-medicated therapy.

What I did not count on was more than 300,000 people dying. And because I live just outside New York City, I was surrounded by death from the beginning.

The idea of death does strange things to us, no matter how young or old we are. I don’t mean the idea that we’re all going to die sooner or later. I mean right here and now. Walk out your door, go to the grocery store, and you might die. Did you wear sterile gloves the first few times you went to the store when this all began? I sure did.

I thought a lot about that famous quip from Samuel Johnson: “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.” So, I found out, does buying bananas and milk.

I brooded over a quote from Flannery O’Connor’s short story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”: “She would have been a good woman,” the Misfit said, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” The imminent possibility of death does indeed make us mind our manners. Some of us anyway.

Forced into house arrest, one tends to take stock, and when you’re done with the big picture stuff, you start in on the little things. Taking domestic inventory, I decided that the great artist and designer William Morris (“Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful”) might judge me harshly. So in that regard I suppose I should be grateful to the new puppy who more or less ate one sofa by himself and then finished the demolition job that the cats had started on another one. We do have a lot less clutter, thanks to Otis. We also don’t have many places left to sit.

What we do have is plenty to read. Our house is like a roach motel for books: they get in but they never leave. And for all I know, they breed in the middle of the night.

Some of these books aren’t beautiful, and some aren’t useful. But most are one or the other, and there are almost none that I would cheerfully part with. Some of them have traveled with me over four decades, across three states and six cities.

Why have a library if you’re not going to use it?

With time on my hands, and thoughts of mortality swirling in my brain, I decided to take a little stock. I would read books I had set aside to read “later,” since there might not be a “later,” and I would read old favorites I hadn’t looked at in years to see how they held up.

With one exception, I consciously chose not to read books about the here and now. I skimmed John Bolton and Bob Woodward only because I’m professionally obligated to keep up with such things. And I had to read not one but two books about Melania Trump—and yes, I was on the clock, and yes, I still want that time back. Trapped like everyone else in the spin cycle of breaking news about impeachment, the election, and COVID, I could not bring myself to add books on current events to my list.

The exception was David Quammen’s Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, first published in 2012, because he’s the best science writer I know of, and because I wanted to learn about zoonotic diseases (and believe me, I now knowingly toss zoonotic into any sentence I can—hey, I did the damn research).

I did choose books with at least a tangential relationship to the present. I started with The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard because I’m convinced that when you’re trapped in a bad situation, nothing cheers you up like a story where people are having a much worse time than you are.

The Worst Journey is a travel-writing classic that I’ve idly meant to read for years, and now I wish someone had kicked my ass a long time ago to dig into it sooner. For in this case, “travel-writing classic” sells this book way short. This is not just a great travel book or a great book about exploration or scientific discovery. It is all those things at once, a book that defies pigeon holes, and in its quiet, self-effacing way, it is one of the most disquieting first-person descriptions of a man going to pieces that I have ever read.

Cherry-Garrard was a very junior member of Robert Falcon Scott’s second and fatal attempt to reach the South Pole. Cherry-Garrard’s story is of a type peculiar to post-Victorian Englishmen (think Lawrence of Arabia) wherein brave young men take on impossible tasks, only to have their boy-scout ideals run through the mangle of war or the elements and come out shattered on the other side. This is the expedition famous for the episode in which one of the explorers, knowing he is going to die and not wanting to burden his companions further, leaves the tent they share and walks into a -40 degree blizzard, saying, "I am just going outside and may be some time." (Bizarre footnote: Both T.E. Lawrence and Cherry-Garrard became close friends with George Bernard Shaw, who strongly encouraged both men to write their classic memoirs.)

Drawing on his own journals and those kept by Scott and others in the expedition, Cherry-Garrard gives his narrative a sort of logbook sameness, such that when disaster strikes, he’s just as matter-of-fact as when describing daily routines. The understatement just makes everything seem even more horrifying, as when a group of men go to bed in tents thinking they’ve made camp on a solid ice sheet, only to wake up the next morning and find that they are floating on top of a small iceberg with their pack ponies trapped on another.

Then there was the small, three-man expedition to collect Emperor Penguin eggs. This is the trek that gives the book its title. For the men embarked on the search, it did not prove fatal, as Scott’s polar expedition would in later chapters, but death was close almost the whole way, and misery was closer. Temperatures fell to 75 below zero, their tent blew away in a blizzard, clothes and sleeping bags were either frozen stiff or sopping wet when they thawed—thawed or not, they were always cold. And almost the entire journey, which spanned weeks, took place in the darkness that prevailed both day and night. Yes, reading about all this suffering did make the pandemic a little more bearable.

It also opened a rabbit hole. From Cherry-Garrard I learned about Herbert Ponting, the photographer who was part of the expedition in its first year, and whose epic images of Antarctica make you understand why Scott and Shackleton and all the rest were so mad to go there. For a month or so I became obsessed with these photographs and the sense of making do in isolation (but with great scenery) that they preserve. And then from Ponting I moved on to other major players in the gothic drama of Antarctic and Arctic exploration—to Larsen, Shackleton, and the rest, even S. A. Andrée, the ill-fated balloonist who tried to reach the North Pole by hot air balloon in 1897, a story best told in Richard Holmes’ Falling Upwards, his addictive history of air ballooning.

I hadn’t read William Faulkner’s Light in August since high school, and it was even better than I remembered. Much better, in fact. To anyone who thinks Faulkner is nothing more than endless, convoluted sentences and Southern gothic obscurity, I say, read this novel. It’s plotted and paced with a rare precision, and its characters are drawn with a hand that never falters, and it matters most for what it says about race in America. Together with Absalom, Absalom! it provides the wisest, most heartbreaking examination of our native tragedy by any white author alive or dead. In the murderous bootlegger Joe Christmas, a man who does not know if he is Black or white, Faulkner gave flesh to the shrieking absurdity of racial hierarchy. And with the vigilante Percy Grimm, he reminds us that thugs like the Proud Boys have been standing by (or worse) in American history for a very long time. Light in August was first published in 1932, but with only the most superficial adjustment it could have been written yesterday.

Cotton Comes to Harlem is probably as tragic as Light in August, at least in its assumptions about human nature and racism in America, but the Black author Chester Himes makes you laugh so hard that you almost forget to cry. In roughly the middle of the last century, Himes wrote a string of detective novels about Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, New York City police detectives working out of Harlem. You can’t call them heroes—there are no heroes in Himes’ stories—because they’re too violent and too willing to bend the law to stop crime. In almost every novel, they get wrist-slapped by their white superiors, who otherwise turn a blind eye to how they do their jobs because, well, it’s Harlem and who cares?

Cotton Comes to Harlem features not one but two scams being run on Harlem’s most gullible residents: one by a fake Black preacher with a back-to-Africa racket and one by a fake Southern colonel who wants to lure Black people back down South. Both are venal, murderous men, and the bloody trails they cut through New York would make a tabloid headline writer reach for the thesaurus. Himes wrote other novels that had nothing to do with cops and crime solving, but it’s as a crime fiction writer that he’s best remembered. Nice that he’s not forgotten, but the label’s too restrictive. Himes wrote as well about New York as Chandler wrote about Los Angeles, and he was cynically smart and funny about race—ironically by not writing explicitly about race: he just wrote about how urban Black citizens lived and coped, and let you draw your own conclusions.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s nothing wrong with being a crime fiction writer. Or so argues my recidivism. This was not my first trip through Cotton Comes to Harlem. I probably reread detective novels more than any other kind of books. I don’t mind knowing in advance who kills who, because I never cared about the plots in the first place. I just like hanging out with the characters. And I like the comfortable groove of the ride—it’s not about the destination, it’s about the getting there.

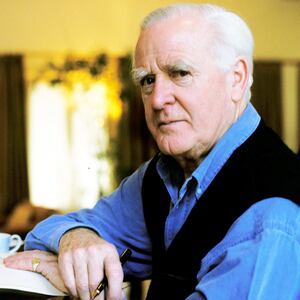

I was rereading Smiley’s People for the second time when I heard that John le Carré had died. This particular—and particularly weird—coincidence had never happened to me before, and yes, it felt creepy, although as with every piece of bad news lately, it also felt apt. It’s 2020, what else would I expect?

The deceptively mild-mannered British spy George Smiley would reappear occasionally in other le Carré novels written after this one was published in 1979, but this is truly Smiley’s last act, his triumph over his nemesis, the Russian spy master codenamed Karla. It’s got a good plot, but the real pleasure is the chance to live inside Smiley’s orderly mind, and a mind coupled to a conscience. In a year when too many at the top of the government seemed more than willing to abnegate all responsibility for the common good, a decent government bureaucrat, even a spy and a fictional spy at that, was a welcome sight.

I read other things too. Thoreau’s wonderful essay on walking. Hilary Mantel’s last entry in her fictional trilogy about Thomas Cromwell (as beautifully written and paced as the first two novels, but why do the third parts of trilogies so frequently disappoint?). I reread Walter Tevis’ The Queen’s Gambit, which is even better than the marvelous new miniseries, and parts of Rebecca, which is better than all the filmed versions. And I’ll probably finish out the year with Faulkner’s novella The Bear, which I try to read every year (just as I try to annually rewatch The Rules of the Game and Ride the High Country).

But you get the idea. Reading is a consolation, even a comfort, especially when you reconnect with old familiar pleasures. It also slows things down. I binge as much TV as the next guy, but I believe those studies that say watching TV leaves us both anxious and exhausted, and who needs more of that this year? Reading sucks me into a comfortable pace, a slow lane where, for an hour or so, I can block out a world gone mad on several fronts. It’s the best over the counter antidepressant I’ve found.

And from the looks of things, I’ll need it a while longer. Even with good news on vaccines, lockdowns here, there, and everywhere are tightening back up. We’re nine months in, and the end is nowhere in sight. If this lockdown drags on much longer, I’ll have to break down and finally tackle Proust.