In his seminal public relations book How to Win Friends and Influence People, Dale Carnegie warns about the risks of confrontation.

"There is only one way to get the best of an argument,” he writes. “And that is to avoid it."

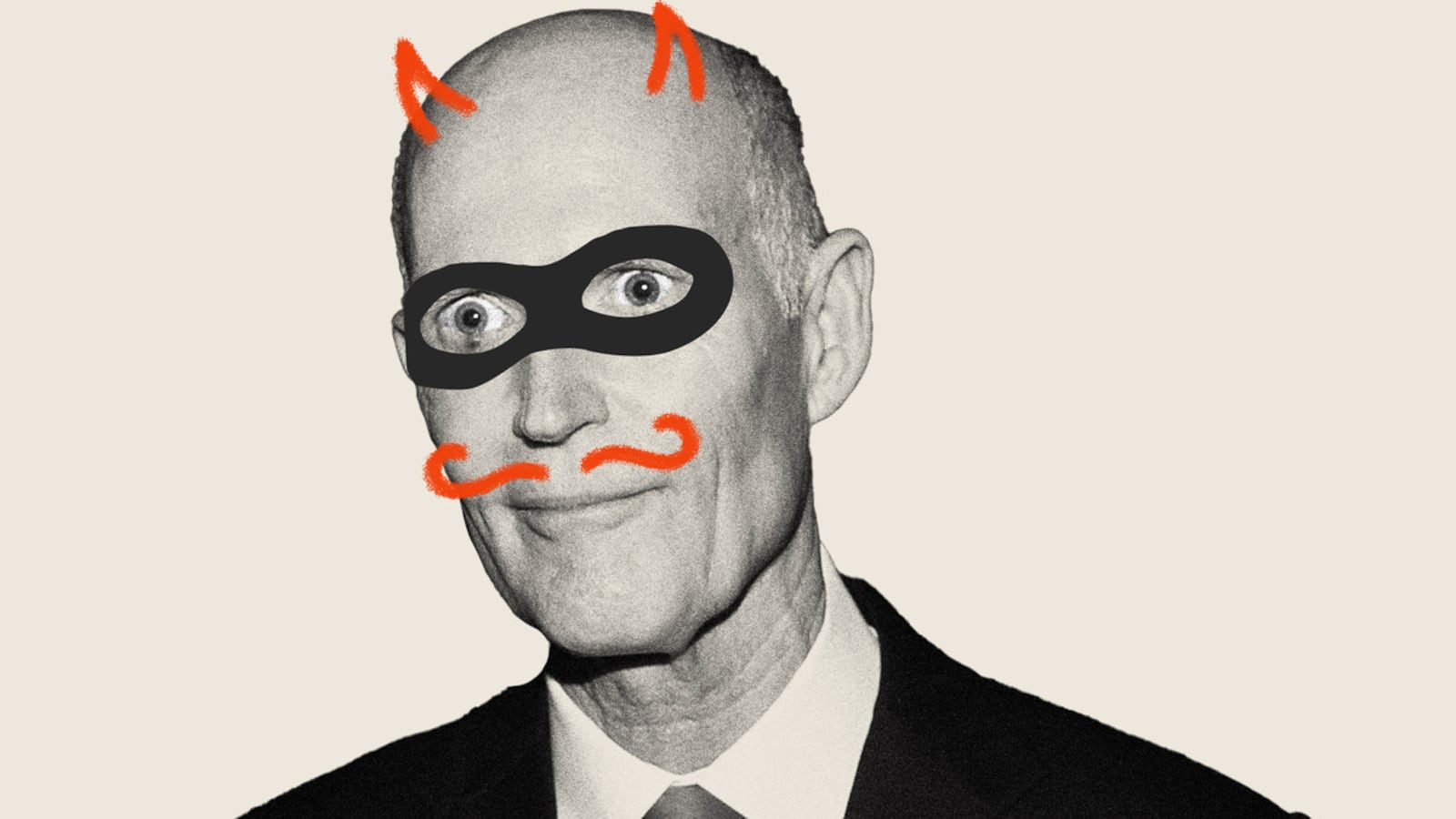

According to The New York Times, Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) rereads the book regularly. He’s even given out thousands of copies to friends and associates over the years.

But Scott’s reputation these days has been most shaped by how eagerly he has followed the opposite of Carnegie’s advice—to Scott, the only way to lose an argument seems to be to avoid it.

A brief rundown of the Florida senator’s frenetic past year demonstrates the point.

Last January, Scott released a platform that proposed putting all federal programs—including Medicare and Social Security—up for negotiation every five years. The move made Scott the leading villain of President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address last month. And it sparked such a bitter feud with Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) that the beef lives on to this day, further fueled by Scott’s campaign to unseat McConnell as leader in the wake of a disappointing midterm campaign both men oversaw.

Even former President Donald Trump, a Scott ally, has admonished him to “be careful, Rick.”

Through it all, Scott has won and lost friends. He’s made fans and enemies. He’s influenced people into either loving him, hating him, or in some cases, loving to hate him.

To hear him tell it though, taking all that incoming—praise from the right, gloating from Democrats, seething from the GOP establishment—is the cost of sticking to his principles.

“I did something we should all be doing,” Scott told The Daily Beast while walking through the Capitol last week. “I put out my ideas, it’s what I believe in, it’s what I ran on, and I represent my state.”

Asked if he’d dispute his inclination to get a rise out of Washington, Scott put his head down and chuckled. “I don’t know about that,” he said, though he expressed surprise that Biden ultimately featured him so heavily in his State of the Union address.

From his admirers to his critics to his colleagues, however, Scott’s provocative moves have left them wondering what, exactly, he is doing.

“I don’t know whether it was a miscalculation on his part, or if he got exactly what he was hoping,” said Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-ND). “Only he knows that, I suppose.”

But Cramer, praising Scott as the “conscience of the right,” added that the Florida senator makes “important points” and has provoked important debate in the GOP.

“I think somebody needs to get a rise out of somebody around here,” said Sen. Mike Braun (R-IN), a Scott ally, “because there’s nothing I like about where we’re headed as a country.”

Of course, this is far from a universal opinion in the party. A senior Republican aide dryly noted Scott’s love of How to Win Friends and Influence People—a book that today seems like it could have been written by ChatGPT, with advice like “be a good listener” and to repetitively use people’s names. The aide noted that Scott’s reliance on the book’s purported wisdom “shows how much this stuff does not come naturally to him.”

“It seems he doesn’t know how to course-correct, so he keeps plowing into different things,” the aide argued. “It doesn’t seem like an effective strategy.”

Even more than his ideas, Scott’s propensity to double and triple down on them in response to criticism has turned him into one of the most beloved GOP foils for Democrats. Perhaps no rank-and-file senator has powered more attack ads, speeches, tweets, and talking points from their opposition than Scott has.

“I, as a Democrat, love Rick Scott and his service to this country and the Democratic Party,” one operative quipped. “I adore him, and I wish him well in his endeavors.”

The broader question looming over Scott’s place at the center of attention in Washington is what he intends to do with it.

At the moment, his only declared plan is running for re-election to the Senate in 2024. A former two-term governor of Florida, and one of the richest men in politics, Scott occasionally garners buzz as a potential presidential candidate. Clearly, Scott has interest in leading the Senate GOP conference, but he’d likely face stiff competition for the job whenever McConnell steps down.

No matter what his grand plan is, there is plenty of political upside for Scott in casting himself as an enemy of both Biden and McConnell. He’s a loyal Republican, said Cramer, but “is his own guy.”

“It’s not like he’s off the reservation—he’s clearly as on the reservation as anybody—but I think for some people, that independence, maybe they just find it difficult for themselves to deal with,” Cramer said.

When asked about his challenge to the longtime leader, Scott framed it more as a referendum on the Senate GOP’s values, not on him specifically. (He lost, 37 votes to 10.)

“The public is mad,” Scott said. “They’re mad. They think, we have a Republican Party out in the real world, we ought to have a Republican Party up here. We ought to stand for what we campaigned on.”

For Scott, taking a stand seems to be as much about actual policy as it is about behaving in a way that party leadership doesn’t. The senator’s 11-point plan to “Rescue America” is a perfect example.

Ahead of the 2022 campaign, McConnell declined to release an official election-year agenda for the party, telling reporters he’d say what the GOP would do with the majority once they won it.

Two weeks later, Scott, then the chairman of the Senate GOP’s official campaign arm, published his plan, which contained no small level of snark for Republican leaders who wanted to return to “Washington’s business as usual.”

Among other things, Scott proposed sunsetting every federal program every five years unless it was explicitly reauthorized by Congress, a ploy to force debate on sweeping, expensive projects—and perhaps kill some of them. Beyond that, he proposed a minimum tax on low-income Americans who pay no federal income tax so they would have “skin in the game.”

In the preface to his platform, Scott predicted it “will be ridiculed by the ‘woke’ left, mocked by Washington insiders, and strike fear in the heart of some Republicans. At least I hope so.”

That prediction came truer than the Florida senator could ever have imagined, and probably in some unintended ways. The Democratic operative, for instance, said they’d never forget the day Scott’s plan came out.

“I remember reading it in Playbook and thinking, we have gold,” they said. “I don’t understand it, and I couldn’t have drawn it up in a lab if I tried.”

Democrats from the White House to Congress to the campaign level rushed to amplify Scott’s plan as proof that Republicans, if given power, would target seniors and the poor in service of small-government orthodoxy. Scott, said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT), is “more confident to put on paper what the broader Republican Party says in private.”

“His views are probably pretty mainstream inside the Republican Party,” Murphy said. “It's just that he’s often a little bit more willing to say it out loud.”

McConnell, and many other Republican senators, quickly moved to quash that perception. The GOP leader reiterated multiple times that the party would not support an agenda that, he said, “raises taxes on half the American people and sunsets Social Security and Medicare within five years.” Then-Sen. Roy Blunt (R-MO), meanwhile, pointedly suggested that Scott should be more focused on winning back the majority.

Amid the furor from both sides, Scott did back down on one thing: he removed his proposal to increase taxes on half the U.S. population. But he stuck to his proposal on sunsetting all federal programs—much to the delight of Democrats—arguing that Congress needed to force a serious debate on the long-term viability of Social Security and Medicare.

“I’ve never suggested to my colleagues that they should pick up my plan,” Scott told The Daily Beast. “What I use it [for] is to talk to the public about what I believe in, and hopefully have a debate about how we’re going to fix this country.”

Members of both parties may agree that a debate on entitlements would be healthy, but most know to be very careful in how they talk about it. Even Scott’s allies acknowledge he was not particularly cautious on that front. “It was probably a mistake to be that specific,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) told The Daily Beast.

“I think he’s trying to solve the problem, got demagogued pretty bad,” Graham continued, “but one thing I’ve learned up here is, no good deed goes unpunished.”

Today, opinions in the GOP still diverge over whether Scott’s unpopular proposals meaningfully harmed GOP candidates or whether they merely were not helpful.

But when the Republican effort to win back the Senate majority failed—which was led by McConnell and Scott, even as they feuded—their respective camps openly warred, exchanging blame over alleged tactical and messaging missteps. Scott’s challenge to McConnell’s leadership fully poisoned whatever comity existed between the two men and their teams.

Republicans publicly insist those wounds have healed somewhat. Asked if there were any lingering tensions in the conference from Scott’s challenge, Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), a close McConnell ally, said no. “Hopefully, we’re all pros,” he said.

Scott, too, insists things are fine, but it doesn’t take long for him to raise perceived slights. Asked about his relationship with the GOP leader, Scott first expressed hope that McConnell would recover from a recent concussion, which landed him in the hospital and, now, a physical rehab facility.

“I mean, I talk to everybody, so it’s fine,” Scott said.

But Scott’s prominent featuring in Biden’s State of the Union managed to raise fresh tensions about his plan—and his place in Washington—a full year after he’d first rolled out the document.

During the speech, Biden argued that “some Republicans” want to sunset Social Security and Medicare. Outraged, the GOP side of the chamber began yelling and shouting “liar!” at Biden, who said he was “politely” not naming who proposed the idea. The raucous moment ultimately became a tool for Biden to proclaim bipartisan agreement that Social Security and Medicare shouldn’t be touched.

In response, Scott accused Biden of lying about him and his plan and claimed that it’s actually the president who moved to cut Medicare. (He did not.)

An exasperated McConnell again went on the record to distance himself from Scott’s plan, going so far as to say that his ideas would prove a “challenge” to him in his re-election campaign—a clear shot across the bow. (Scott, in turn, told The Daily Beast the comments were “inappropriate” and alleged McConnell was “puppetting” Biden’s talking points.)

Even Trump, to whom Scott has been a close ally, distanced himself from the ideas, as he ramps up his 2024 presidential election campaign.

It’s unclear if that was the final straw, but amid this final round of uproar, Scott finally amended his plan to exempt Social Security and Medicare from sunsetting every five years. To drive home the point, he introduced a bill to increase funding for those programs.

After some 15 months of attacking, explaining, defending, and feuding, Scott’s capitulation may offer a somewhat warped example of a bit of wisdom from How to Win Friends and Influence People.

“By fighting you never get enough,” Carnegie wrote. “But by yielding, you get more than you expected.”