MOSCOW — Salekh carried a slender black leather briefcase and his long, skinny fingers were running nervously all over it, drumming as if on piano keys. Several times during the interview he unzipped the folder to pull out two envelopes, the letters from the court rejecting his petition to stay in Russia. The latest one was dated November 3, 2016.

Salekh is from Aleppo, Syria, but was in Russia when bombs destroyed his home in that martyred city. Now he is one of many thousands of Syrians who hope Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has engaged his country so heavily in the Syrian War, will give them legal shelter until the fighting is over.

But Salekh told The Daily Beast that he is running out hope in the Russian legal system.

In November, facing the judge in the Moscow court, 32-year-old Salekh, normally a mild-mannered tailor, just lost his temper.

“The judge told me that life in Aleppo, where they are bombing every day, was actually fine, that I should go back home to Syria; so I told her straight away: ‘My chopped off head will be sent back to you and thrown upon your desk, then it will be too late for you to give me the refugee status.’”

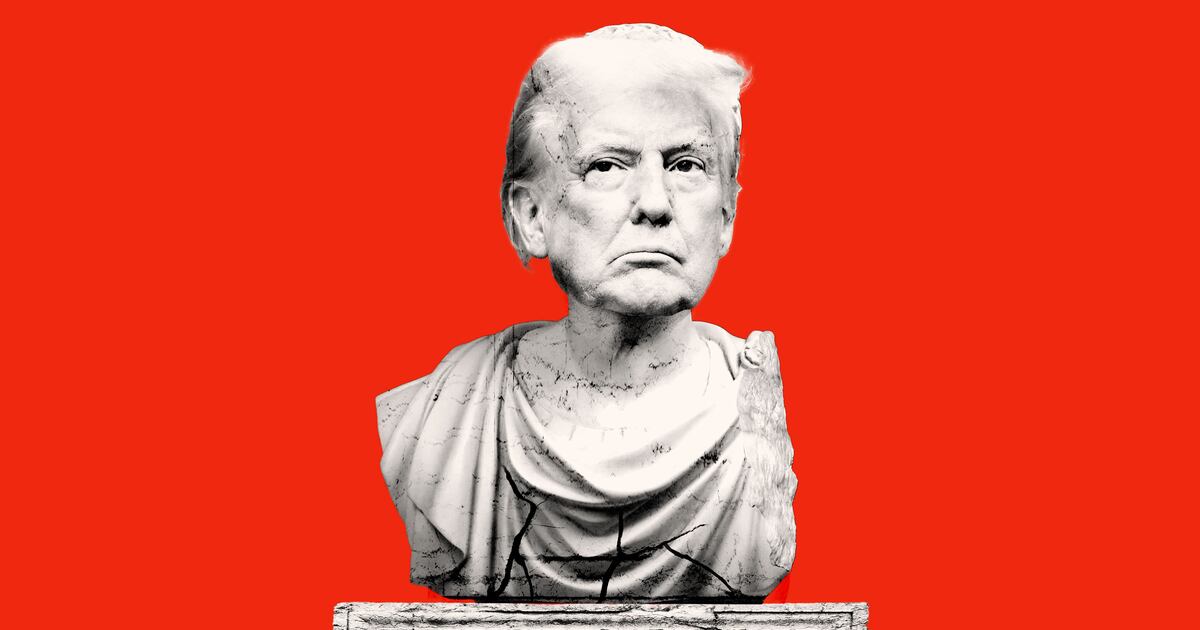

That week Russian rockets targeted east Aleppo as President Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump discussed “regulating conflict” in Syria.

Salekh’s angry story made everybody in the Civil Assistance reception room grow quiet.

From early morning to late night, foreign visitors from the Middle East, Africa, former Soviet countries and Asia came here to see attorneys in the only NGO providing legal help to refugees and illegal migrants in Moscow.

Next to Salekh, Julienne Madiende Macondo, a refugee from Congo, and her friend Marwa Mansur Ali, a refugee from Yemen, were trying to cheer up Julienne’s four-month-old baby daughter. Both women escaped wars and threats in their own countries and for over a year have been trying to get temporary asylum in Russia.

“Almost every other day either police stop me to check my papers or somebody yells at me about the color of my skin,” Macondo told The Daily Beast.

“Nobody in Russia cares about the war in Yemen,” said Marwa Mansur Ali. “At least they show Syria on the news here.”

On Unity Day, Nov. 4,, hundreds of Russian far-right activists joined the Russky March demonstrations all across the country, chanting their usual: “Russia is for Russians!”

The annual event traditionally has terrified immigrants. But this year far fewer ultra nationalists dared to participate in the march, since authorities have cracked down on activists espousing Nazi ideology in Russia. But the ideas do not disappear from people’s minds.

“Judging by how firmly authorities reject our pleas for help, the negative attitude toward black people seems to be deeply rooted in the minds of the public and the state,” says Marwa Mansur.

Macondo, 26, escaped from one nightmare in Congo to find herself in another horror story in Russia. Last year, her husband, a photographer and reporter, was abducted. Macondo, who was in the early stage of pregnancy, received death threats on the phone. She was desperate to get away.

By pure accident, she says, she met a Russian man in Brazzaville, who told her that he worked for the Russian government and could help her escape from Congo. A few weeks later Macondo arrived in Moscow with a Russian visa in her passport to find out that the Russian men inviting her had a sinister plan: Macondo’s Russian host locked her in his apartment and raped her for more than two months, until she managed to escape and find Civil Assistance, who provided her and her newly born daughter with a shelter.

Since 1990 over 50,000 refugees, illegal immigrants, and internally displaced persons from the Caucasus regions, Middle East, Africa, Ukraine and Central Asia have been provided free legal support by the Civil Assistance group.

This year its founder and director, 74-year-old Svetlana Gannushkina, received the Right Livelihood Award, known as “the alternative Nobel Prize,” for her courage.

But the Kremlin does not see Civil Assistance in a friendly light. Last year the Russian Ministry of Justice labeled the NGO “a foreign agent” working on grants from Western foundations.

“That was basically the same as condemning us for being spies,” Gannushkina said in a recent interview, shaking her grey head in frustration.

But neither Gannushkina nor any of her colleagues had time to worry about the long-term future of their group. They believe that any country’s respect for democratic and humanitarian values is defined by its treatment of refugees.

From early morning the reception room at the Civil Assistance office in downtown Moscow is crowded with desperate people like Salekh.

“Try to guess how many Syrians running from the war have received official refugee status in Russia,” Gannushkina says with evident emotion. “Only two people so far, out of almost 10,000 Syrians running from the war to our country.”

“What a shame!” she says, “In the last two to three years Russia has provided not more than 700 people with an official refugee status, and fewer than 300 of them were Ukrainian refugees,” she added.

“Look, the bottom line is Russia does not want to see any of these refugees here,” Gannushkina waved to the reception full of asylum seekers. “We often hear that from officials.”

The fate of Ukraine’s refugees is especially ironic. Nearly one million Ukrainians have fled the war in the Donbas region. But since November 1, Ukrainian citizens have to obey the same visa rules as any other foreign residents staying on the territory on Russia; in other words, although Donbas towns are still being shelled from all directions, Ukrainians are not seen as refugees in Russia any longer, the Civil Assistance lawyer Illarion Vasilyev explained.

The worst nightmare for the team of Civil Assistance attorneys is to receive a call with news about a client being picked up by the Russian security services and passed along to those of their home country.

“We hurry to get a ban on deportation from the European Court of Human Rights—such ban in most of the cases stops Russian authorities from deporting our clients; but sometimes, as in the recent case with an Uzbek client in Kazan, authorities ignored the ban and deported the asylum seekers anyway,” says Vasilyev.

Out of thousands of Syrian refugees coming to Russia, only a few received temporary asylum before the latest crackdown. Last year Hasan and Gulistan Ahmads were camping in Sheremetyevo airport for almost seven weeks before they finally received a temporary permit to stay in Russia for one year.

Why would Russia not give Salekh and other Russian-speaking Syrians a chance to do something good for this country? The first time Salekh came to Moscow in 2010 he loved the Russian capital, he told The Daily Beast. A small Russian company producing bed sheets officially employed him and even registered his name in an employment record book that he immediately fished out of his leather file folder to demonstrate to The Daily Beast reporter. “I am not going to give up, I will appeal the court’s decision again and again,” Salekh said firmly, “Deportation would mean death for me.”