Sargent Shriver’s signature achievement was no sure thing. Peace Corps volunteer John Coyne on how Shriver worked the levers in a skeptical Washington to make a dream come true. Plus, George McGovern on Shriver’s “boundless heart” and Adam Clymer on how Shriver changed America.

In the Peace Corps of the early 1960s, to “Shriverize” an idea meant to enlarge it and apply greater imagination, and then speed up its execution. As an English major, I had never heard the word, but as I learned the lingua franca of the new Peace Corps, this verb would change my life. A Midwestern Catholic boy, I had come of age with the presidency of John F. Kennedy and was a small part of the New Frontier as a Peace Corps volunteer. Like thousands of others, I was going off to change the world. And I was Shriverized by the man himself, R. Sargent Shriver.

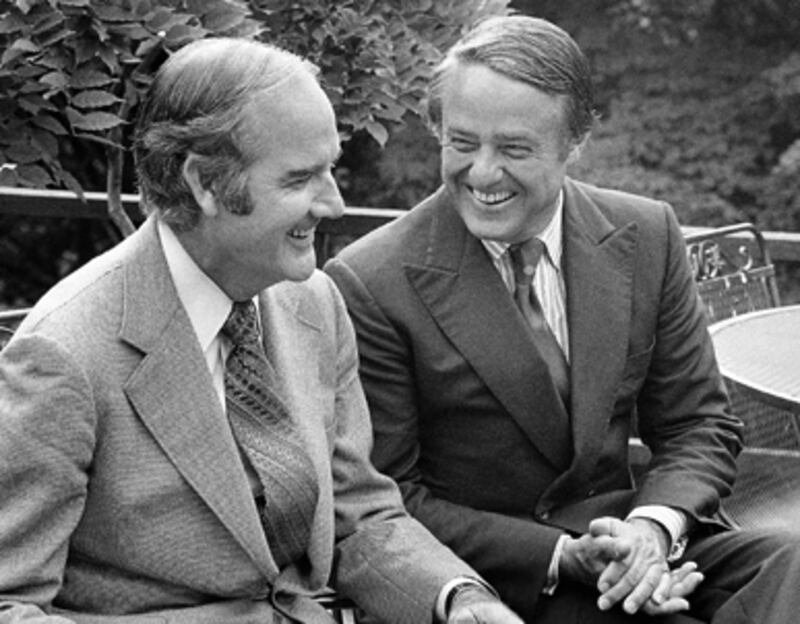

Gallery: Photos: Sargent Shriver

If it hadn’t been for Shriver, there wouldn’t have been a Peace Corps. He took an idea, half-conceived by his brother-in-law Jack Kennedy in an impromptu campaign speech at the University of Michigan, and developed it into an agency that Time magazine in 1961 would call the greatest achievement of the new administration. And the reason it became such a big success—both instantly and even now, 50 years later—was Sarge.

From the very beginning, Shriver saw the Peace Corps as an idea whose time had come. He knew it could be bigger than its tiny budget, bigger than the number of people who actually served. He recognized that it could become a face of the United States, an image of peace to balance the reigning Cold War, arms-race, imperialistic image this country had.

And he didn’t mind fighting with the president in order to realize his vision.

In the first days of his administration, Kennedy wanted a smoothly run foreign policy. To that end, the advisers who forged it—John Kenneth Galbraith, Henry Labouisse, and Lincoln Gordon—created a new super foreign-assistance agency called the Agency for International Development and tucked the Peace Corps into a tight little corner of it.

Shriver hand-sold the idea of a Peace Corps in the hallways and offices of Capitol Hill, one member at a time.

While that probably made sense on a foreign-aid flow chart, Shriver knew that subordinating the Peace Corps to a massive bureaucracy would be disastrous in recruiting the kind of idealistic, non-business-as-usual types he wanted as volunteers; it would suffocate its ability to get close to the communities it served. And he told Kennedy and his aides as much.

Shriver’s warning was ignored by the White House, the State Department, and the new AID. Bill Moyers, then a former aide to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, observed, “The employees of State and AID coveted the Peace Corps greedily. It was natural instinct; established bureaucracies do not like competition.”

So Shriver began to work the back rooms of the White House and, with the help of Moyers, convinced the vice president to lobby Kennedy into letting the Peace Corps have its freedom. But even as he agreed, JFK required that Shriver pay a price. Kennedy told his sister Eunice, who was Shriver’s wife, words to this effect: “If Sarge doesn’t want me to have it in AID where I wanted it—let him go ahead and put the son of a bitch through Congress on his own.”

If Kennedy hoped that the daunting prospect of operating without presidential backing would force his brother-in-law to cave in, he was wrong. Shriver hand-sold the idea of a Peace Corps in the hallways and offices of Capitol Hill, one member at a time. Harris Wofford tells the story of how a congressman, a member of the House Rules Committee, remembered Shriver: “One night I was leaving about 7:30 and there was Shriver walking up and down the halls, looking into doors. He came in and talked to me. I still didn’t like the program but I was sold on Shriver—I voted for him.”

Shriver’s determination and passion made the Peace Corps into a program that has remained true to its ideals for 50 years. In these days of rancor in the halls of Congress we can only wish we had more legislators and officials who wear their hearts on their sleeves, and who know how to Shriverize an idea that can help make the world better.

Novelist John Coyne served at a Peace Corps volunteer in Ethiopia from 1962 to 1964. He is the editor of peacecorpsworldwide.org.