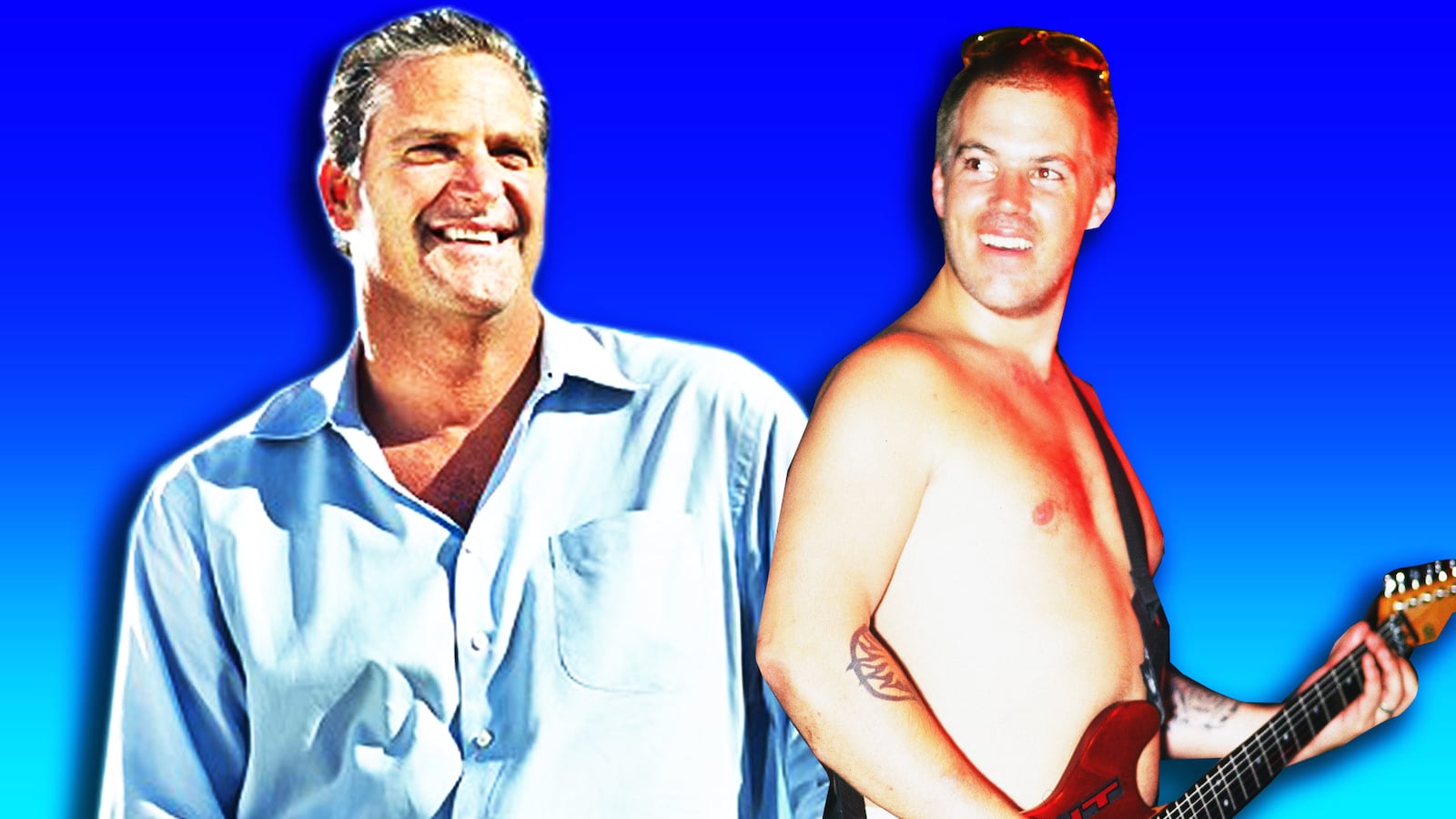

You never expect to be one of the people whose lives are turned inside out in one single moment. But where one story ended, a new one began—starting in the depths of murky grief and poisonous pain, and how we transformed that into the hard-fought redemption of not only myself, but all those touched by the death of my friend, Bradley Nowell, lead singer of Sublime.

May 25th, 1996. I drove up to San Francisco to see my friends from Sublime play a string of shows prior to the beginning of their first European tour. There was a buzz of excitement in the air as they had just recorded this brilliant new album, and I think we all felt this was the “magical bomb” that was going to explode—that people were going to hear it, and all their years of hard work were going to finally pay off. I was so proud of this body of work; it was set to be a night of celebration for what was just around the corner for our friends: great success.

A bunch of us were in Petaluma to see Brad, Eric and Bud play for two-plus hours, bleeding and sweating their songs for a ravenous audience. We had been partying all day and into the evening before the show. I was already six years deep into my prescription painkiller addiction, which began as a result of a lower back surgery in 1990. I was popping Norco’s like Pez candy, and had established a network of separate doctors and dealers to feed my insatiable appetite for the drug.

I had rented one of those huge Lincoln Town Cars, and after the gig that night the members of Sublime crammed into the “mafia mobile.” Totally intoxicated, I made a worthless attempt to back out of the theater parking lot but instead of going in reverse I charged forward, pounding directly into a concrete wall, which is when Sublime’s manager Blaine Kaplan ran up to the car and yelled, “Zman, I am taking over from here!” I didn’t put up a fight, and clamored into the back seat next to Brad. We drove back to San Francisco where the band had a sold-out show the next night.

All of us spent the car ride in a haze. Brad had his head on my shoulder almost asleep, mumbling, “I miss my wife and my son.” He repeated those words a few times but it was enough that I’ll never forget it. They echo even now in my memory, despite my drugged-out state of mind. Those were the last words I would ever hear my friend speak.

Blaine dropped off the band members at their hotel and drove me and my buddy Pat Conlon back to his house so we could sleep it off. Later that night, at about 4:00 a.m., Brad called Blaine’s house to speak to me. I was in one of the guest rooms and unable to take the call. The following morning, we awoke to discover the tragic news: our friend and brother Bradley James Nowell had died from a heroin overdose in his hotel room.

An Exclusive Clip from The Long Way Back:

Pat and I drove like two crazed, hungover madmen to the airport and jumped on an emergency flight back to Santa Barbara. My friend and I were so distraught the airlines took pity on us and didn’t even charge us for the tickets. That’s how we must have looked when we got to the airport—utterly shattered.

Our minds fixated on the Nowell family, baby Jakob and Troy (Brad’s wife), and how long the bus drive must have been back to Long Beach for our friends, with our dear friend in the freaking morgue in San Francisco. There weren’t enough Kleenex to mop up the damn tears.

A lot of us unraveled with Brad’s passing—myself included. It wasn’t long after that a drug called OxyContin was introduced into my world. It was already becoming a problem on the East Coast, but at that time it was barely known here on the West. Hell, I hadn’t even heard of it. But as my grief enveloped me, I obsessed about not being able to take my friend’s 4:00 a.m. phone call. “What could I have possibly done to change things? Could I have possibly helped reverse the outcome? What did he want to say?”

I had zero coping skills, and with the introduction of Oxy into my world, my drug addiction worsened. I found myself in a place where the drug dominated me and I was relegated to a state of being completely antisocial, and quite scary. My skin was often grey and I would constantly sweat. The business I had succeeded in was collapsing, and even worse, I was imploding emotionally and physically. A sickness had taken a hold of me that is difficult to describe, and I was mired in a level of desperation so sincere that, years later, I’m still unsure if I can even articulate it.

Ten years passed. I was in Vancouver, B.C. with a girlfriend during the Christmas time in 2006. I had been taking 400 OxyContin a month and one of my doctors found out about the other, so he stopped prescribing, resulting in 240 Oxys being removed from my sick regimen. I would chew morphine pills to try and make up for the loss but it just wasn’t working anymore. As my girlfriend would be in the shower I would stand out on the ledge of the balcony in my robe each morning wanting to end it all on the cold pavement. To just do it. To just end this pathetic life and dive off the 19th floor. The only thing that saved me was the thought of my mother, and how this would just destroy her, so I would hesitantly step back off the ledge, and for another day, just not commit suicide.

It was two months later when my heart was skipping beats that I crawled into South Coast Hospital in Laguna Beach. I was dying from drug addiction, yet I had no clue what was in store for me. I went through a sinister detox: I didn’t sleep for 44 days, and my skin crawled and limbs shook for months. That was my jackpot payoff for almost seventeen years of prescription painkiller addiction. Slowly—very slowly—I regained my physical health. But recovering physically was only a part of the process. I found a program of recovery and with the help and guidance of the men in that program, I was able to learn how to get emotionally healthy. One of the key components to staying sober is to give what you learn in the program back to others. So I dedicated my life to helping others who struggle with addiction. After a couple of years I was taken under the wing of a master interventionist in Orange County, and he taught me the right way to compassionately work with families and get their sick loved ones into treatment. I loved the work and in time started my own company.

God works in mysterious ways. I was eight years clean and sober and traveling all over the U.S. doing my work. Never could I have predicted what happened next. I received a call from Papa and Janie Nowell regarding Jakob Nowell, Brad’s son, who was struggling with his own drug and alcohol addictions. My heart immediately sank. “Can we get together and talk about this?” We met ten minutes later.

What transpired in that booth at the coffee shop was a wide range of emotions. We were all on a mission to do anything we possibly could to help Jakob get off the path he was on, and to avoid what happened to his father. Papa Nowell has said it time and again: “I couldn’t go through it again... It wouldn’t work for us emotionally, it just wouldn’t.”

Jakob and I went through the rollercoaster ride of first just getting comfortable in early sobriety. We spent a tremendous amount of time together—counseling, mentoring, doing sober trips, attending a ton of recovery meetings, bonding, fighting a lot, crying a bit, and ultimately coming out the other side.

Outside of my own recovery, having the opportunity to have Jakob in my life has been a gift. It’s full circle in a way, and a great deal of healing has taken place as a result of it. Sometimes when I’m surfing, or while in prayer or meditation, I would like to think that Brad is with us, and I believe in my heart that he’s proud of us, and that’s there’s a sense of good in what we are doing with our lives. At the end of the day, there’s nothing more fulfilling for me than that.

Z-Man’s story is chronicled in the new documentary ‘The Long Way Back,’ available Oct. 17 on VOD platforms.