Which state has produced more presidential nominees than any other in the last sixty years? It’s not a trick question, but the answer is both surprising and puzzling.

Virginia was once known as “the mother of presidents” because four of our first five presidents (George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe) hailed from the Old Dominion. Virginia’s dominance actually made sense since that state was by far the largest of the original thirteen, in terms of both land area and population.

More recently, the same logic might suggest that California or Texas would be the prime source of presidential nominees since these are the two top states in population, and ranked numbers two (Texas) and three (California) in land area. The Lone Star and Golden States have played significant roles in recent presidential politics, with Texas generating three nominees (Lyndon Johnson and the two George Bushes) and California producing two (Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.)

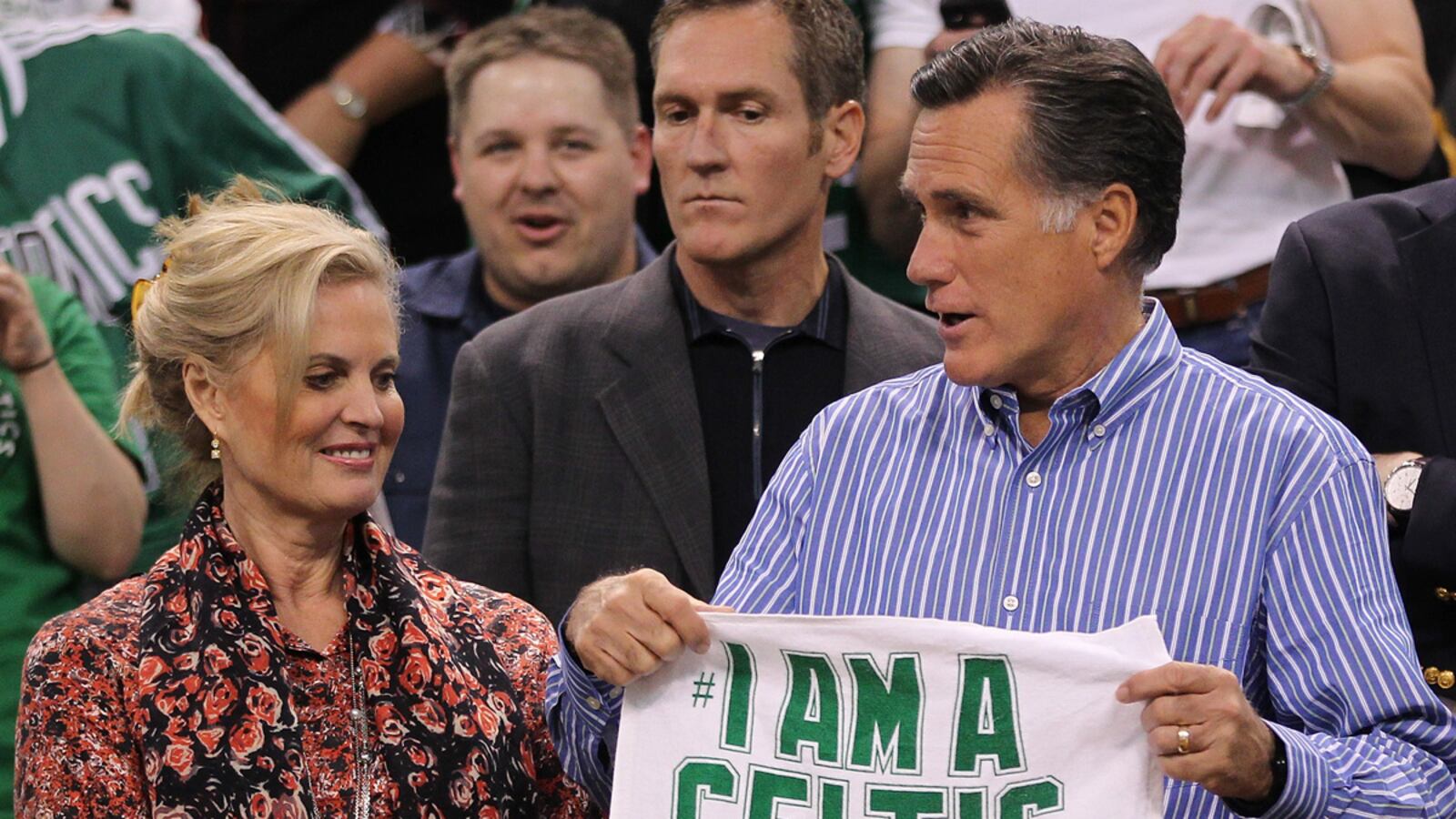

But it’s actually Massachusetts, of all unlikely places, that’s the odd winner of the nomination sweepstakes, with four—count ‘em, four!—major party nominees since 1952. This unlikely presidential breeding ground gave the nation John Kennedy, Michael Dukakis, John Kerry, and now Mitt Romney. The Bay State also produced other formidable contenders who fell short of winning the nomination, including Ted Kennedy in 1980, Paul Tsongas in 1992, and Henry Cabot Lodge, a vice presidential nominee in 1960 and briefly a presidential contender four years later. Meanwhile, two other prominent presidential aspirants were born in Massachusetts (Robert Kennedy and George H. W. Bush) though they both ultimately represented other, larger states (New York and Texas) when they ran for elective office.

Why would this relatively minor state, ranked 44th in land area and only 14th in population, play such an out-sized part in presidential politics?

Massachusetts hardly counts as a significant swing state like Florida or Ohio; it delivers only 11 electoral votes and, barring some freakish landslide (like Reagan’s sweeps in ’80 and ’84) invariably goes to the Democrats. In 1972, Richard Nixon and the GOP won 49 states—only Massachusetts stood firm to its Democratic roots. In presidential campaigns, Democrats can afford to take Massachusetts for granted and Republicans can cheerfully write it off, with even former Governor Romney all but conceding his opponent will carry the state he once led.

For both parties, nominating a candidate from Massachusetts offers no practical advantages, especially since much of the rest of the country seems to dislike or resent snooty Bostonians. During the primary campaign, virtually all of Romney’s Republican opponents regularly derided him as a “Massachusetts Moderate” or even “Massachusetts Mitt,” as if the mere invocation of this effete bastion of supercilious liberalism would discredit their rival in other corners of the continent.

For three reasons, however, Massachusetts has produced a steady stream of presidential candidates and will almost surely continue to do so.

First, the state has nurtured a long tradition of treating its top politicos like rock stars – or, perhaps more appropriately, like the sports stars cherished by rabid fans of the Red Sox, Celtics, and Patriots. In the Revolutionary era, “Sons of Liberty” leader Sam Adams led the original Tea Party, a piece of street theater featuring vandalism and Native American disguises. John Hancock, the egotistical and fabulously wealthy merchant who signed his name larger than the rest of his colleagues on the Declaration of Independence, fancied himself the true leader of the new nation and smoldered when George Washington eclipsed his glory. Sam’s cousin John Adams may have been a controversial figure in the rest of the colonies (and, ultimately, a one-term president) but he remained a sage and dynasty founder at home. His son, John Quincy Adams, also lost a re-election bid after a single turbulent term as president, but came home a hero and got himself elected to the House of Representatives for eighteen more years of service.

In the same era, Massachusetts voters literally worshipped the beloved Senator they proudly called “the Godlike Daniel,” forming an admiring cult around the incomparable orator Daniel Webster. He served as Secretary of State twice, and made frequent lunges at the presidency without ever securing a nomination from his Whig Party. Republican Calvin Coolidge enjoyed more national success as an ardently admired governor and one of the most popular chief executives of the twentieth century. Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, the charming rogue James Michel Curley served in Congress and the governor’s mansion, before winning four terms as Mayor of Boston—one of which he served largely from his prison cell. His flamboyant personality inspired the 1956 bestseller The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor, as well as the nostalgic John Ford-Spencer Tracy movie based on the book.

Of course, when it comes to charming rogues and pop idols in Massachusetts politics, no one can touch the Kennedys with their five generations of fanatical devotion. JFK’s grandfather, John Francis Fitzgerald, won election as Mayor of Boston and earned the nickname “Honey Fitz” for the honeyed tenor voice with which he serenaded his adoring constituents. Now the great-great-grandson of Honey Fitz, Joseph P. Kennedy III (Bobby Kennedy’s grandson) has announced his candidacy for a Congressional seat and already inspired talk of future presidential runs.

In addition to the local obsession with colorful and contentious politics, the educational resources of Massachusetts certainly play a role in producing the string of presidential candidates. It’s no accident that three of the four recent Massachusetts nominees (Kennedy, Dukakis, and Romney) all held degrees from Harvard, the nation’s oldest, most prestigious university. John Kerry, on the other hand, had to content himself with graduating from Yale in Connecticut before he returned home to pursue politics and attend law school at Boston College.

The presence of an unrivaled number of elite colleges (Harvard, MIT, Amherst, Wellesley, Mount Holyoke, Amherst, Williams, Smith, Boston University, Boston College, Northeastern, Emerson, Tufts, and many more) leads a disproportionate number of the nation’s most ambitious and driven students to make their way to Massachusetts; some of them who arrive from other states (like Michigan-born Romney and Vermont-born Coolidge, who graduated from Amherst) inevitably decide to stay there.

In an era of ferocious competition for top academic slots and a relentless emphasis on meritocracy, its cluster of venerable educational institutions gives the Bay State a formidable advantage. On the Supreme Court, for instance, all nine of the current justices hold degrees from Yale or Harvard. All four of our most recent presidents also hold Yale or Harvard degrees, and if Mitt Romney wins that will be five in a row.

The final feature of Massachusetts culture that inspires presidential runs involves the state’s historic sense of destiny and self-importance. On the very occasion of the founding of Boston, Puritan leader John Winthrop delivered his famous sermon comparing the new settlement to the Biblical “City on a Hill,” inspiring the whole world with its excellence and righteousness. Boston also quickly seized the designation “Cradle of Liberty,” though Philadelphia, a much larger town, served as the colonial capital and Virginia produced more significant leaders and crucial battles in the War for Independence. In 1858, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. dubbed Boston “the Hub of the Universe” based on its role as a center of intellectual and political ferment—a particularly obnoxious title given the town’s status as only the fifth most populous city in the nation. (New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and even Brooklyn – then separate from Manhattan—boasted more residents, but Brooklyn never claimed to be the Hub of the Universe).

The educational excellence of Massachusetts colleges of course fed this preening self-regard, producing precisely the sort of utopian grandiosity that breeds presidential candidates. When John Kennedy sought the White House in 1960, he not only proclaimed that America stood on the edge of a “New Frontier” but deployed a campaign slogan declaring “A Time for Greatness.” Michael Dukakis made his race 28 years later, boasting of his gubernatorial achievements as leader of “the Massachusetts Miracle.” The leaders of most other states—especially other states with limited population and economic clout—would feel far more reluctance to trumpet their own records as frankly “miraculous.”

This association with greatness, splendor, and epic achievement actually helped produce Mitt Romney’s most dubious accomplishment during his single term as governor. If he had served as Chief Executive of Michigan (like his father), or Utah (where he led the Olympics), Massachusetts Mitt might have felt less compulsion to produce some monumental reform to ornament his record. But if you lead the State House at the Hub of the Universe, you’re more likely to sign on to precisely the sort of epochal overreach represented by Romneycare – an overreach that leaves you vulnerable to harsh questions if not attacks from your fellow conservatives.

Massachusetts thinkers and office-holders have always fancied themselves philosopher kings who know better than the unenlightened masses in lesser states, and feel some obligation to spread their wisdom and righteousness to more benighted precincts. From John Winthrop and the Adamses, to Emerson, Thoreau, Alcott, and abolitionist firebrand William Lloyd Garrison, Bay State bombast has never shied away from the deep-rooted local instinct to tell the nation how to live.

Of course, this could be a serious problem for Romney, which helps explain the Democratic strategy to discredit him as a Boston grandee who deep in his heart believes he’s better than the rest of us. Fortunately for Mitt, however, he’s not the only national candidate who conveys the same impression: Barack Obama himself spent enough time at Harvard to drink deep of the Cambridge Kool Aid and to convey his own echoes of Massachusetts pretentiousness and self-righteousness.

According to the New York Times, the two over-achievers currently contesting the presidency first met while sharing the stage for Washington’s gridiron dinner at year’s end in 2004. According to witnesses, the newly elected Senator from Illinois teased the then-governor of Massachusetts about his much-discussed presidential ambitions, urging him to “go for it.” Reflecting on John Kerry’s losing presidential campaign, Obama jabbed Romney by declaring, “I hear Massachusetts is a great launching pad.”

Though the future president meant his comment ironically, for various reasons he wasn’t far from the truth.