Excerpted from Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2015 The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

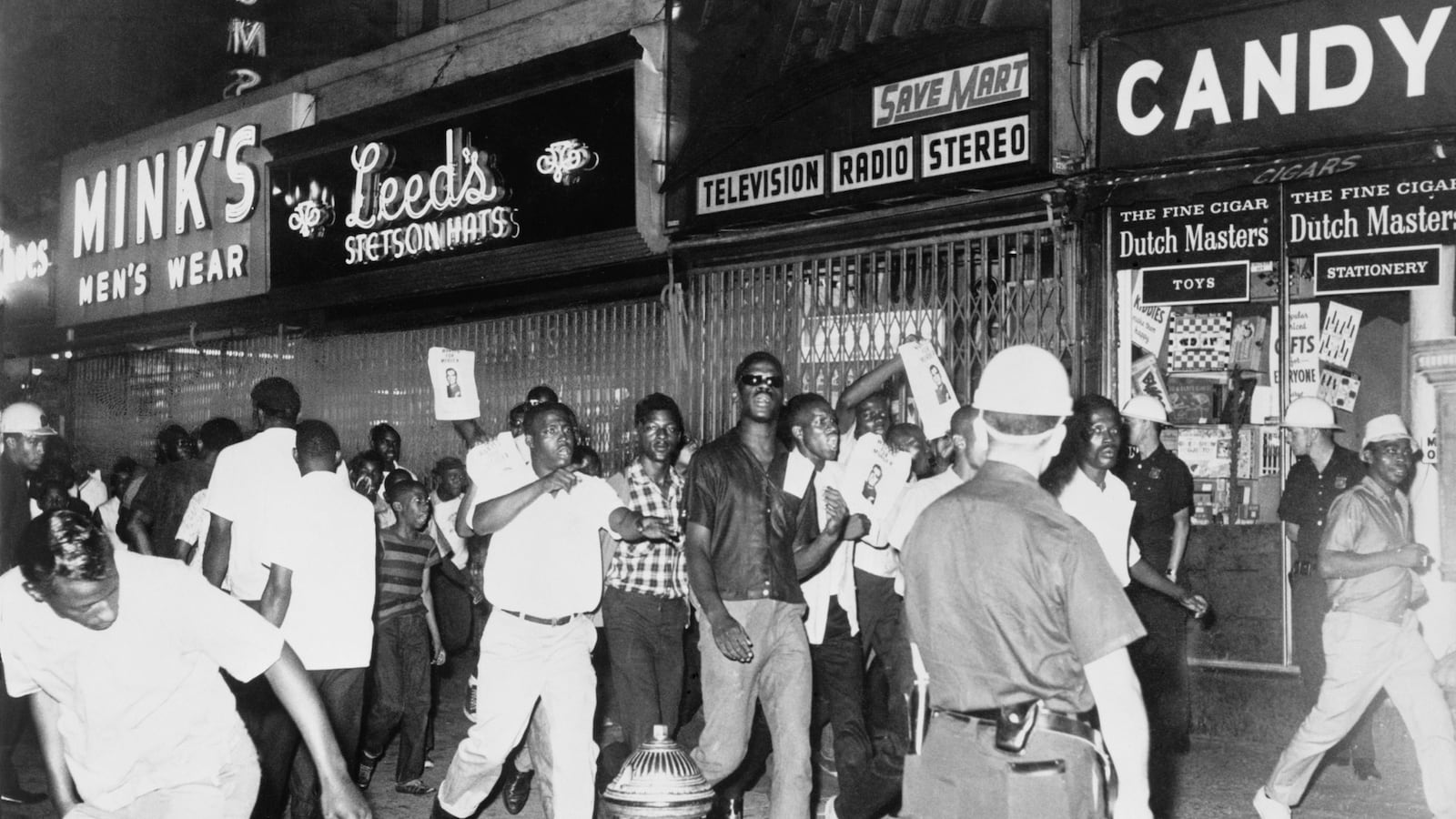

In order to discern the origins of the black silent majority majority, it is important to hear the grievances working—and middle-class African Americans accumulated over the late 1960s and early 1970s.

As drug addiction, crime, and urban blight grew unabated, black attitudes continued to exhibit great distress. New York City’s black community rated drugs and crime as its top concerns. In November 1971 an aide to U.S. Senator Jacob Javits forwarded him a “progress report” that Representative Charles Rangel mailed to his constituents. In the newsletter, Rangel discussed the results of a recent questionnaire, noting, “There was almost unanimous consent that narcotics is our number one problem, followed by housing and lack of State and City services.” In the memorandum that accompanied the document, the aide wrote, “Rangel’s survey confirms what you and I already know: drugs and housing are the major issues.” In 1973 the Amsterdam News and radio station WLIB conducted a poll that asked, “What is the single issue in New York today that Blacks should be more concerned about?” Consistent with the findings of Rangel’s survey, about 60 percent listed drug abuse, 58.7 percent listed housing, and 58.3 percent listed education. The residents felt as if they were drowning in an awful confluence of social pathology, insecurity, and visible signs of urban decay. That same year, Louis Harris and Associates, based on their recent survey of Harlem residents, concluded, “The cumulative impact of the feeling of powerlessness, of the feeling that the neighborhood is declining, of the awareness that major problems of crime, drugs, housing and employment exist, and that community services and facilities are, for the most part, inadequate is that a majority of residents do, indeed, feel trapped.”

Churches and their parishioners felt trapped. In 1966 Rev. Edward T. Dugan of the Roman Catholic parish of the Resurrection, a mostly black parish of 1,800 people, disclosed that a survey of his parishioners indicated that “the average person had been held up at least once.” After attributing the crime problem to “poor junkies,” Father Dugan described the situation “as a tragedy for the little people.” Many churches reduced the number of nighttime services and activities because “many residents refuse to leave their homes at night.” Rev. E. G. Clark, pastor of Harlem’s Second Friendship Baptist Church, stated, “Because of the circumstances, 90 percent of the people refuse to come out at night… even on Sunday.” Moreover, black churches, despite their sacred place in the community, were not spared. These sanctuaries were frequently compromised and looted: “Burglars broke into Salem Methodist Church… and stole 15 typewriters used in a job training program sponsored by the church and Eastern Airlines. They came back two weeks later and stole a tape recorder and a record player. A block away burglars stripped Williams Institutional Methodist Episcopal Church… of its public-address system and microphone… Although the church had hired a night watchman, they broke in again and made off with the chancel carpet.” Given the centrality of the church to African American social life, this criminal activity affected a large segment of the community, particularly the elderly. In 1966 a small survey of senior citizens in Bedford-Stuyvesant indicated that only 13.3 percent never attended church. Around 40 percent attended regularly, and another 25.2 percent occasionally.

Local businesses found themselves in similar dire circumstances. Crime closed off access to and degraded the quality of the consumers’ republic that black entrepreneurs had built. Mrs. Cleo Weber, owner of a beauty parlor, reported that her “shop had been burglarized twice in less than three months.” Expressing her own consternation with Harlem’s drug and crime problem, Weber said, “You have a little business and you struggle so hard, and you can’t even carry your money home at night… And you can’t say anything to these people. You’re afraid to. They’re dangerous.” Lou Borders, whose clothing store had been burglarized twelve times in twenty years, said, “That soul brother stuff—you can forget about it.” Borders, owner of one of the oldest black stores in Harlem, asked, “How much can a man take?” A small 1972 survey of mostly minority firms in Bedford-Stuyvesant suggests that experiences were quite common. Of the nineteen business owners interviewed, fifteen reported being negatively affected by crime and twelve indicated they had installed security devices to protect their business.

When asked to identify the “main cause” of their troubles, more named addicts than any other factor. A representative from the black-owned Carver Bank interviewed for a different study of Bedford-Stuyvesant conducted in 1970 and 1971 echoed these concerns: “We’ve noticed the reluctance of many of our customers— especially the older ones—to come in and make deposits in their savings accounts. I’ve had more than one tell me things like ‘It may be only ten dollars, but one of these guys is really hard up, he’d mug you for ten cents.’ ” The female owner of a small candy and cigarette store in Bedford-Stuyvesant was more blunt: “Whether they’re still on a high, or just coming down from one, they’re the most dangerous. Why don’t I leave? Lady, how old do you think I am? Where would I go?

All in all, drug addiction and related crimes posed an existential threat to churches, businesses, and civic organizations. Because of racial segregation, these firms and organizations had developed a niche in black communities, but crime had threatened their viability. Not only were they victims of drug addicts, but their members and customers were so afraid of being mugged by junkies that they no longer attended meetings or patronized businesses. In 1965 Philip A. Smith, chairman of East Harlem’s Upper Madison Avenue Community Association, wrote Senator Robert F. Kennedy, “We have made repeated complaints to the police and other authorities regarding the rapid increase of addicts coming into and roaming through our neighborhood… People are desperately afraid to walk the streets. As a consequence, houses of worship, community organizations, and adult education centers have noted a sharp decrease in attendance, and our merchants are adversely affected. Crime, indeed, murder, is now a part of daily life.” Six years later, the Amsterdam News reported that “some sections of the so-called Harlem business section after nightfall [look] like a ghost town. People continue to be afraid to walk the streets at night. Churches, lodges and other fraternal organizations curtail or even discontinue services and meetings.” The editorial added, “The Silent Majority of Harlemites who sit by and watch their community be taken over by the criminal elements without taking any kind of stand are simply surrendering to these elements.”

Yet “the Silent Majority of Harlemites” did not sit by and watch. They fought. Many advocated for drastic measures. Reverend Clark declared, “We need constant patrolling, but we’ve begged for patrolmen but we can’t get them.” “Oh, they come over, but they al- ways leave,” he added. James Lawson, head of the United African Nationalist Movement, complained, “They have 360 plainclothes men… and 320 of them are on from 8 until 4 and they are out chasing numbers writers, numbers control and small black number bankers. They should be working on narcotics and protecting the individual citizen.” He also criticized the courts, saying, “The judge will give a numbers writer six months but someone who robs some poor innocent person gets off with 60 days.” Reverend Dempsey, who declared that “[i]t’s gotten out of hand,” rehashed old complaints and refurbished old proposals: “Take the junkies off the streets and put ’em in camps… Sure, the Civil Liberties Union and the N.A.A.C.P. would howl about violation of constitutional rights. But we’ve got to end this terror and restore New York to decent people. Instead of fighting all the time for civil rights we should be fighting civil wrongs.”

Not everyone embraced this punitive impulse—at least not completely. Andrew Gainer, whose Harlem hardware store had been burglarized fourteen times in two years, advocated a mix of law enforcement and structural solutions. He shouted, “To hell with civil liberties!… People are being destroyed by dope and crime every day. Yes, let’s bring back the Tactical Police Force. I’d even bring mounted police.” At the same time, Gainer stated that he and a group of local business leaders, Harlem Citizens for Safer Streets, would lobby Governor Rockefeller for a program of free narcotics for addicts, a three-year rehabilitation program, and job training.

However, a 1971 survey of Harlem business owners indicates that this was the minority view. The top four proposed solutions for the community’s crime problem were punitive: “stricter law enforcement and an improved court system” (21 percent), “more policemen” (16 percent), “take junkies off the street” (9 percent), and “more severe punishment for criminals” (6 percent). In contrast, only 4 percent listed “curb unemployment,” and only 2 percent listed “rehabilitation of addicts and criminals.” Capturing the smoldering resentment among Harlem’s business leaders, the New York Times reported, “Harlem’s Negro merchants and clergymen, alarmed by what they regard as a rising tide of criminal violence by blacks against blacks, are demanding harsh punitive action. These middle-class Negroes say they want the Tactical Force, a symbol of police brutality to many Harlem residents, assigned to all Harlem precincts.” Thus most businesses in Harlem sanctioned only part of Gainer’s program. They rejected structural solutions and said, “To hell with civil liberties!”

Caught in the throes of urban decline and social disorganization, working- and middle-class African Americans were under siege and overwrought. Their “respectable” lives, which they had worked so hard to create, were now being jeopardized by ne’er-do-wells stealing their property and accosting their person. These offenses and frequent affronts on houses of worship and businesses nurtured the punitive impulses of working- and middle-class Harlemites. Given the threats that drug addiction and crime posed to working- and middle-class African Americans, many in Harlem and other black neighborhoods in New York City felt they constituted a “silent majority” of decent, law-abiding citizens victimized by the recklessness and immorality of a dangerous minority. They felt imprisoned by drug addicts. And they responded in kind. They now believed policing and prisons—the systematic removal of junkies—represented their own path to salvation. Lou Borders, Mrs. Weber, and others spoke to these complex emotions and evaluations: the sinking feeling that junkies were beyond repair and that society had refused to notice; the firm belief that political institutions had abnegated their responsibilities and that “decent citizens” had become liberalism’s sacrificial lamb and criminals had become its cause célèbre; and the ever-present and throbbing sense that enough was enough.

Daily indignities ignited a grassroots movement against crime, a fierce backlash against junkies, pushers, “thugs,” and “vagrants.” Tired and angry, working- and middle-class African Americans were not afraid to give the governor a piece of their mind. After one visit to Harlem did not go well for the governor, Wyatt Tee Walker, a former aide to Dr. Marin Luther King Jr., informed the governor, “The black community is in a very ugly mood and have some very legitimate reasons for being so. Most of it is despair, and any candidate who comes into their midst will feel the brunt of their venom and hostility.” This event was not unique. Rockefeller “was repeatedly confronted with the drug problem by angry residents at his ‘town meetings’ in black communities.” African American ministers frequently charged that “drugs were being openly sold on the streets of Harlem without police interference and demanded action.” Before an address at a meeting of the 100 Black Men, Joe Persico warned him, “Questions are expected to deal with drugs[,] crime, black business opportunity… government opportunity for blacks.” Of course, “government opportunity for blacks” did not encompass the needs and aspirations of the community’s poor. Like “black business opportunity,” it was a call for more opportunities for mostly middle-class African Americans.

The community’s anger was on full display during a town hall meeting Governor Rockefeller held in Harlem in 1967. Attendees mentioned most of the community’s pressing problems, including housing, sanitation, and jobs. Crime, however, was clearly the top concern. As Rev. Ivan Moore, pastor of Walker Memorial Baptist Church, put it, “The members of my congregation are afraid. Fear is the worst thing that confronts us.” He told the governor, “Twelve years ago I had… evening services. This [had to be] curtailed because [of] the snatching [of] pocketbooks and crimes against the parishioners.” Moore called for a meeting with city officials, including representatives from the local precinct, because he wanted “to get down to brass tacks” and because the “people of our community, the respectable people, should hear a voice or the voices of our city and our state, stating to them that there is some possibility of handing out some hope for some protection.” Comptroller Mario A. Procaccino, a symbol of white backlash in New York City, also attended the meeting and spoke to the community’s anxieties. He declared, “The upswing in crime, and particularly crimes of violence, has reached a point where the number one preoccupation of our citizens—yes, even before jobs, housing and education—is the fear for their safety and the safety of their families. Our City has become a city of fear.” Then the comptroller proceeded to outline his anticrime strategy. In addition to proposing several innocuous items, such as improving street lighting and creating a system of “police-alarm boxes” similar to fire-alarm boxes, he advocated a very punitive approach. He criticized lenient sentences doled out to juvenile offenders, saying, “Consideration ought not to be given to the young hoodlums who commit crimes of such violence and viciousness as to demonstrate a total disregard for the lives of others.” Then he proposed that “the State legislature designate as crimes such acts as the mugging and knifing of victims and assaults with a dangerous weapon, when such acts are perpetrated by anyone over the age of thirteen years of age.” Despite the harshness of his views, his comments were “interrupted by applause several times.” Others questioned his strategy. Rev. Moran Weston, rector of St. Philip’s Church, remarked, “There is no doubt that the pastors who have spoken are correct in what they say—that there is great fear on the part of many people.” But, Weston contended, the “basic cause of crime is [pervasive poverty], reaching every area of our life and our community.” He maintained that Procaccino’s approach constituted “revenge on young people and adults who are victims of experience.” But the available survey evidence indicates that most Harlem residents and businesses sided with Procaccino’s approach.

In 1969 a hearing of the State Joint Committee on Crime provided working- and middle-class African Americans another opportunity to voice their frustrations; their testimony exposed the tensions in black anticrime attitudes. Everyone described the challenges in similar terms: “citizens” were being victimized by “junkies.” The speakers supplied a variety of theories for the problem: some blamed organized crime, some blamed structural conditions, and some blamed lax law enforcement. Some articulated a mix of behavioral and structural explanations. Senator Paterson “declared that the root causes of crime must be attacked meaningfully. In addition to a poor educational system, unsatisfactory housing and health conditions, and inadequate or no-advancement type jobs (all of which are the status quo in Harlem), a very important root cause of increasing crime is disrespect for the law, its enforcement and its administration. Addicts are everywhere visible and easily identified, but nothing appears to be done.” Paterson’s remarks underscore the ideological contradictions permeating black opinions: the same people who believed that broader social forces were partly responsible for Harlem’s crime problem drew on their class-based morality to hold individuals responsible for Harlem’s condition. The first position calls for jobs, social services, and rehabilitation; the second calls for punishment.