In 1995, Pope John Paul II issued a message on the 50th anniversary of World War II, stating that “the Christians of Europe need to ask forgiveness, even while recognizing that there were varying degrees of responsibility in the events that led to the war.”

Over the next several years, against the advice of certain cardinals, John Paul made a startling call for the church to engage in “the purification of historical memory.”

For a church that considers popes to be infallible—perfect in truth on matters of dogma—the idea of acknowledging its failures in the mud of history was a dramatic shift. In time, John Paul issued a line of apologies to church victims and for such mistakes as the prosecution of Galileo and the past institutional support of slavery. The pope who had endured the Nazi horror in a Polish seminary took special note of “sufferings inflicted upon Jews.” In 1998, the Vatican issued We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah with John Paul’s expressed hope that it might “help to heal the wounds of past misunderstandings and injustices.” We Remember states:

We cannot know how many Christians in countries occupied or ruled by the Nazi powers or their allies were horrified at the disappearance of their Jewish neighbours and yet were not strong enough to raise their voices in protest. For Christians, this heavy burden of conscience of their brothers and sisters during the Second World War must be a call to penitence. We deeply regret the errors and failures of those sons and daughters of the Church.

We Remember avoids comment on the Vatican’s role “in meditating on the catastrophe which befell the Jewish people, on its causes, and on the moral imperative to ensure that never again such a tragedy will happen. At the same time [the decree] asks our Jewish friends to hear us with an open heart.” The document does say:

Addressing a group of Belgian pilgrims on 6 September 1938, Pius XI asserted: “Anti-Semitism is unacceptable. Spiritually, we are all Semites”… Pius XII, in his very first Encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, of 20 October 1939, warned against theories which denied the unity of the human race and against the deification of the State, all of which he saw as leading to a real “hour of darkness.”

The reality behind both of those events, as David I. Kertzer demonstrates in The Pope and Mussolini, was sanitized in the 1998 Vatican version. A distinguished historian at Brown University, Kertzer has advanced John Paul’s call for “purification of the historical memory” in a manner that the pope could probably have not imagined.

In drawing on archives the Vatican has recently made available, Kertzer explores the milieu of church officials around Pius XI—notably the Secretary of State, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, who would become the next pope, Pius XII—in a devastating account of how Vatican officials gave passive support to Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime as it began persecuting Jews in alliance with Hitler, over the protests of the dying pope.

Pius XI’s now-famous remark (“Anti-semitism is unacceptable. Spiritually, we are all Semites.”) was the cry of a defeated man. He had made huge concessions to the authority of Mussolini, legitimizing the dictator in a very real sense, for what the pope expected would be a strengthening of the church. Near his end and knowing he had been betrayed, the pope spoke in a “voice [that] trembled” to the “staff of Belgian Catholic radio,” writes Kertzer. But in that audience at the Vatican, there was no radio to broadcast. His dramatic words were airbrushed from L’Osservatore Romana, the Vatican newspaper of record, which operated outside the tentacles of Fascist censors. Citing state intelligence files, Kertzer notes the surprise of Fascist secret police on the Vatican’s silence about a papal statement.

“How exactly Pacelli and his undersecretary [Monsignor] Domenico Tardini, had ensured that the Vatican newspaper ignored the pope’s explosive remarks remains a mystery,” writes Kerzer. “Most of the pages from Pacelli’s log of his meeting with the popes in these months are, curiously, missing from those open to researchers in the Vatican Secret Archives.”

There is little mystery otherwise in this thorough-going account for which Kertzer also did research in the archives of the Jesuit community of Rome. The complexities within that religious order, renowned for its scholars and loyalty to the pope, make for a numbing leitmotif.

Father Tacchi Venturi became the pope’s personal envoy to Mussolini; the Jesuit wanted secret police to spy on Italy’s Jewish bankers and was fully behind Mussolini’s hammer-stroke nationalism. In 1938 the pope summoned Father John LaFarge, a New York Jesuit and author of Interracial Justice, asking him to “secretly draft an encyclical on what the pope considered to be the most burning questions of the day: racism and anti-Semitism,” writes Kertzer.

“I am stunned. The Rock of Peter has fallen upon my head,” LaFarge told a friend. He ran into opposition from the Superior General of his own order, Father Wlodzimierz Ledóchowski, a Pole who harbored hostile views of Jewish people and insisted on providing two priests to assist LaFarge. Ledóchowski arranged for the encyclical to be watered down and worked with others to have it tabled as the pope faced his final illness.

Kertzer pulls off a considerable achievement in his portrait of Pius XI who emerges in the final chapters as a figure bordering on the tragic. The early chapters cover a political seduction story.

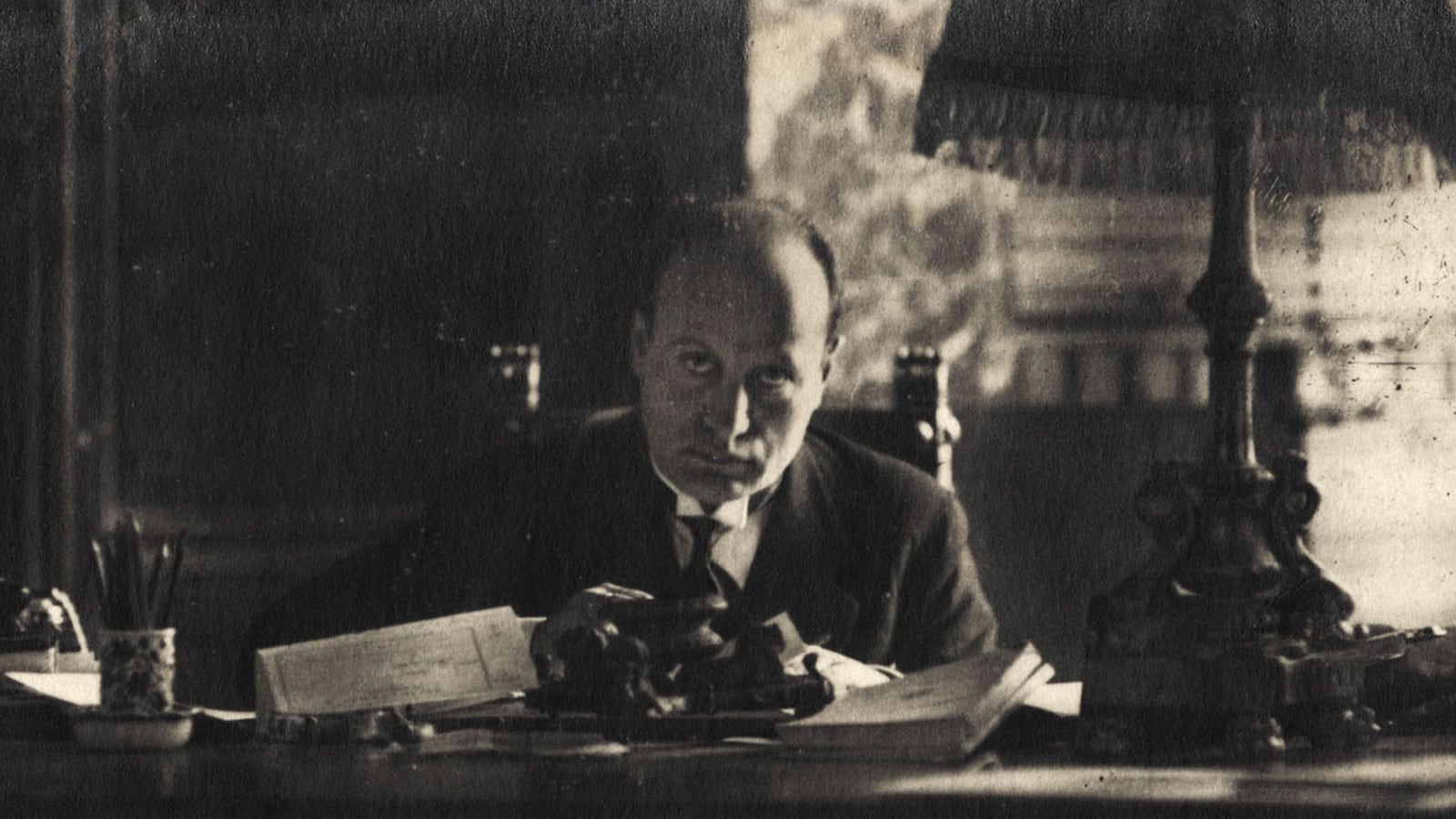

Aloof and bookish, Pius XI (Achille Ratti) spent years as a Vatican librarian before becoming a diplomat and cardinal. As pope, he grew quickly into the role of religious monarch, insisting that his own brother call him “Your Holiness” and “Holy Father.” He ate alone, walked an hour each day in the Vatican gardens with a monsignor at a careful distance behind him, refused to be photographed or speak on the telephone. The pope wanted greater church authority in Italy, notably free reign for the Catholic Action movement of parish groups in alliance with bishops up the ladder to the Vatican; he also wanted financial reparation for loss of the Papal States, a large farming region in central Italy, after the 1870 Italian unification. The pope of that era, Pio Nono—Pius IX—had declared himself a prisoner of the Vatican in refusing compensation as part of a diplomatic relationship with Italy. For six decades, no pope left the 108-acre city-state.

Mussolini rose in the early 1920s using Fascist hit squads to murder opposition figures and terrorize independent parties, unions, even Catholic-owned banks. A narcissist who juggled mistresses around his common-law family, Mussolini was more hostile to Catholicism than his papal point man, Father Venturi, was toward Jews. But as a demagogue for whom total power meant all, he realized that to capture Italy he needed the church. To woo the pope he had his children baptized and eventually married their mother, an anti-clercalist herself who went along in support of his ambitions.

With the muscular charisma of a Caesar, “Il Duce” appealed to a fractured country with a weak economy. The Catholic Popular Party was an emerging presence, a million members strong, between Socialists and Fascists in the parliament. Mussolini targeted the Catholic party in his courtship of Pius. “As Fascist bands continued to attack local Catholic Party leaders and headquarters, Mussolini cast himself as the only person able to control these overzealous Fascists,” writes Kertzer.

He bowed to the Vatican’s request that only books approved by the Church be used to teach religion in the schools. He agreed to close down gambling halls. He provided state recognition of the Catholic University of Milan, announced his opposition to divorce, and moved to save the Bank of Rome, closely tied to the Vatican, which was on the verge of bankruptcy. Crucifixes were back in the country’s classrooms, and Church holidays were added to the civil calendar.

Pius ordered the priest who led the Catholic Popular Party to resign. As it disbanded, Mussolini went about gutting Italian democracy, solidifying power in himself, “Il Duce,” as personification of the Fascist state.

In 1929, the Holy See and Italy agreed to the Lateran Accords, which the historian Father Hubert Wolf has called a “pact with the devil.” The Vatican City became a sovereign state with ownership of key properties in Rome. Catholicism became Italy’s official religion. The Holy See had freedom in appointing bishops. Italy paid about $92 million in compensation for parts of Rome and the Papal States, the region lost to the national unification of the 1870s. The Vatican reinvested about 60% of its windfall in government bonds.

The anti-semitism voiced in L’Osservatore Romana, the Jesuit-edited La Civilità cattolica and other church journals as quoted in Kertzer’s narrative surely fall under “the heavy burden of conscience” alluded to in We Remember of 1998. The fear of Bolshevik Communism fueled a scape-goating of Jews, particularly those in Russia, as La Civilità cattolica (Catholic Civilization) editorialized in 1922 on “this tiny minority today [which] has invaded all the avenues of power and imposes its dictatorship on the nation.”

“To build support for its anti-Semitic campaign, the government continued to rely heavily on Catholic imagery, citing Church texts,” writes Kertzer.

By 1938, when a depleted Pius tried to raise his voice against Italian race laws and policies targeting Jews in line with the Nazis, the Catholic Church beyond him was in virtual lockstep with the Fascists.

Mussolini gained stature with Wall Street and Western interests through the 1929 pact; but fusing his visions of glory into an alliance with Hitler put Italy on a disastrous path to war. Pius was too late in what he wanted his words to do.

“The Vatican had not protested the ejection of Jewish children or Jewish teachers from the schools, nor that of Jewish professors from the universities,” writes Kertzer of the situation by 1937. “Neither Pacelli nor the pope’s two emissaries…[including] the unofficial Jesuit [Venturi] had ever uttered a word to challenge the government’s decision to treat Jews as a danger to a healthy Italian society.”

Pacelli’s silence, as Pius XII, on the Nazi genocide, was the subject of John Cornwell’s provocatively-titled 1999 best-seller, Hitler’s Pope, a book that drew a scholarly counter-attack on certain points that caused the author, in a revised paperback edition, to retract some of his criticism.

Kertzer mentions Cornwell’s book once, on the second-to-last page of the epilogue (curiously omitting it from his bibliography) and simply lays out the dispute, stating that Pius XII’s “defenders argue that he was the best friend Jews ever had.” But in his treatment of Pacelli’s record of Secretary of State, Kertzer draws a staggering contrast on the tepid impact of his 1939 encylical, as Pius XII, warning of an “hour of darkness.”

The darkened hour gave way to years of genocidal warfare under the Nazis as Mussolini’s ill-trained troops steadily lost ground. The persecution of European Jews was indeed, as John Paul II noted in 1995, “marked by varying degrees of responsibility.” But the role of the Vatican under the last two popes called Pius lodges deep in that responsibility. If John Paul’s call for “purification of the historical memory” has any meaning to the church, Pius XII’s candidacy for sainthood—put in motion by Paul VI in the 1960s, long before the truth was out—should be halted once and for all.

What a disaster it would be in the church’s efforts to atone for its history of anti-Semitism if Francis or any future pope were to make a saint of Pacelli. The Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of the Saints has 99 pages of footnotes in Kertzer’s book which pinpoint records in the Vatican and elsewhere in Rome worth consulting.

Kertzer credits John Paul II with opening the files on the Pius XI papacy, in 2002, which made him decide to embark upon the book. The Pope and Mussolini matches rigorous scholarship with a fair yet forceful prose voice. It is an impressive work of history.

Jason Berry is author of Render unto Rome: The Secret Life of Money in the Catholic Church.