Fifty years ago this month, Charles Avery left his high school in Jefferson County, Alabama, to lead about 800 of his fellow students on a 10-mile walk to Birmingham City. They were stopped by the sheriff’s department, arrested, and jailed. “I was put in the paddy wagon with Dick Gregory and his writer,” says Avery, who was 18 at the time and president of his senior class. “I would never forget that day.”

In 1963 Birmingham was known as one of the most racist cities in the South. Martin Luther King Jr. had described it as a “symbol of hard-core resistance to integration.” Activists had nicknamed it Bombingham, because of the frequency of violent attacks against those fighting the system of segregation.

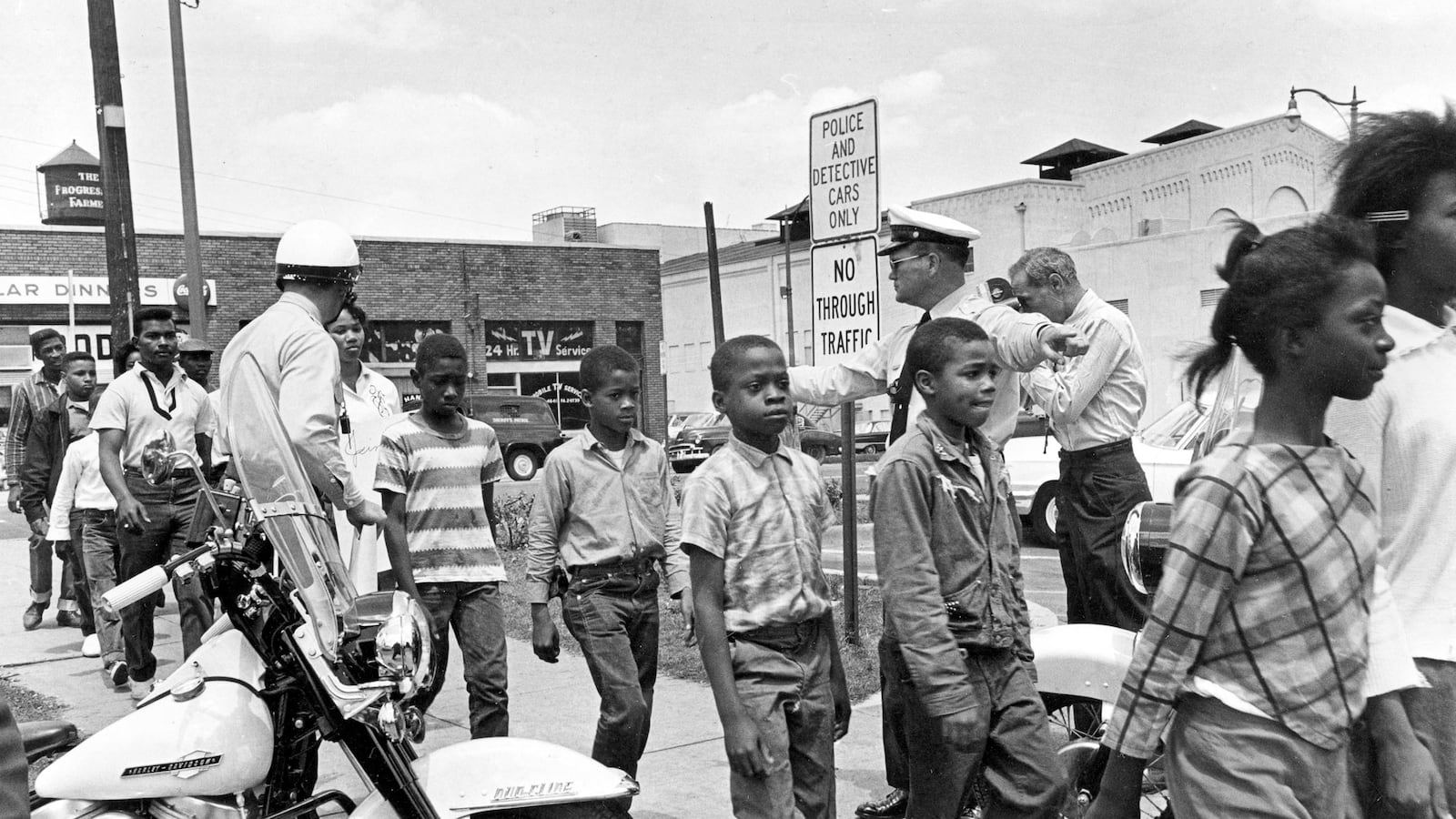

It was the Rev. James Bevel, a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and adviser to King, who came up with the idea of a protest group made up of children. In May 1963 they launched the Children’s Crusade and began a march on Birmingham. By the time Avery made it to the city May 7, more than 3,000 black young people were marching on the city.

It was King’s words that inspired 16-year-old Raymond Goolsby to participate in the march.

“Rev. Martin Luther King stood right beside me,” remembers Goolsby, 66. “He said, ‘I think it’s a mighty fine thing for children, what you’re doing because when you march, you’re really standing up; because a man can’t ride your back unless it is bent.’ And, boy, I mean he talked so eloquent and fast, after he finished his motivational speech, I was ready.”

On May 2, 1963, Goolsby joined thousands of students who left their classrooms and gathered at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. It was there where they spilled out in groups of 50 to march downtown. “My group was the first of 50 to march,” says Goolsby. “Our job was to decoy the police. We got arrested about a block and a half from 16th Street.”

The next day, the police, led by infamous commissioner of public safety Bull Connor, brought out fire hoses and attack dogs and turned them on the children. It was a scene that caused headlines across the nation and around the world.

“Pictures of the bravery and determination of the Birmingham children as they faced the brutal fire hoses and vicious police dogs were splashed on the front pages of newspapers all across America and helped turn the tide of public opinion in support of the civil-rights movement’s fight for justice,” says Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund.

Jessie Shepherd, then 16, was soaked when she was loaded up in a paddy wagon. “I was told not to participate,” says Shepherd, now a retired clinical diet technician. “But I was tired of the injustice.”

“I couldn’t understand why there had to be a colored fountain and a white fountain,” says Shepherd. “Why couldn’t I drink out the fountain that other little kids drank out of? As I got older, I understood that’s just the way it was, because my skin was black, and we were treated differently because of that.”

So she marched.

Soon the city’s jails were so overcrowded that students were sent to the local fair ground. They slept on cots and sang freedom songs while waiting for movement leaders to raise money for their bail.

“I didn’t anticipate the outcome being so drastic,” says Shepherd.

Gwen Gamble had just been released from jail and didn’t want to go back. Shortly before the crusade, the teenager had been arrested for participating in a lunch-counter sit-in and jailed for five days. “We were put in with people who had actually broken the law. It was scary. They weren’t nice,” says Gamble, who was 15.

She and her two sisters were trained by the movement to be recruiters for the Children’s Crusade. On the first day of the march, they went to several schools and gave students the cue to leave. They then made their way to 16th Street Baptist.

“We left the church with our picket signs and our walking shoes,” says Gamble. “Some of us even had on our rain coats because we knew that we were going to be hosed down by the water hoses.”

Under intense public pressure, Birmingham negotiated a truce with King, and on May 10, Connor was removed from his position. The Children’s Crusade had worked.

“The Birmingham campaign was a crucial campaign,” says Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. “He had never led a massive campaign of civil disobedience before, and there were not enough adults prepared to be arrested. So the Children’s Crusade turned the tide of the movement.”

Carson also notes that had King failed in Birmingham, his legacy wouldn’t be what it is. “If he hadn’t won, there probably wouldn’t have been an ‘I Have a Dream‘ speech or a Man of the Year award or a Nobel Peace Prize in 1964,” says Carson.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the march, there will be a reenactment of the Children’s Crusade and the opening of an exhibit on the children’s march at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Today Birmingham has an African-American mayor, a majority-black City Council, and a black superintendent of schools.

“Had it not been for those children going out in the streets of Birmingham making a difference, going to jail, protesting, I really don’t believe what we have to day would be possible,” says Gamble. “I definitely say there would not be a Barack Obama."