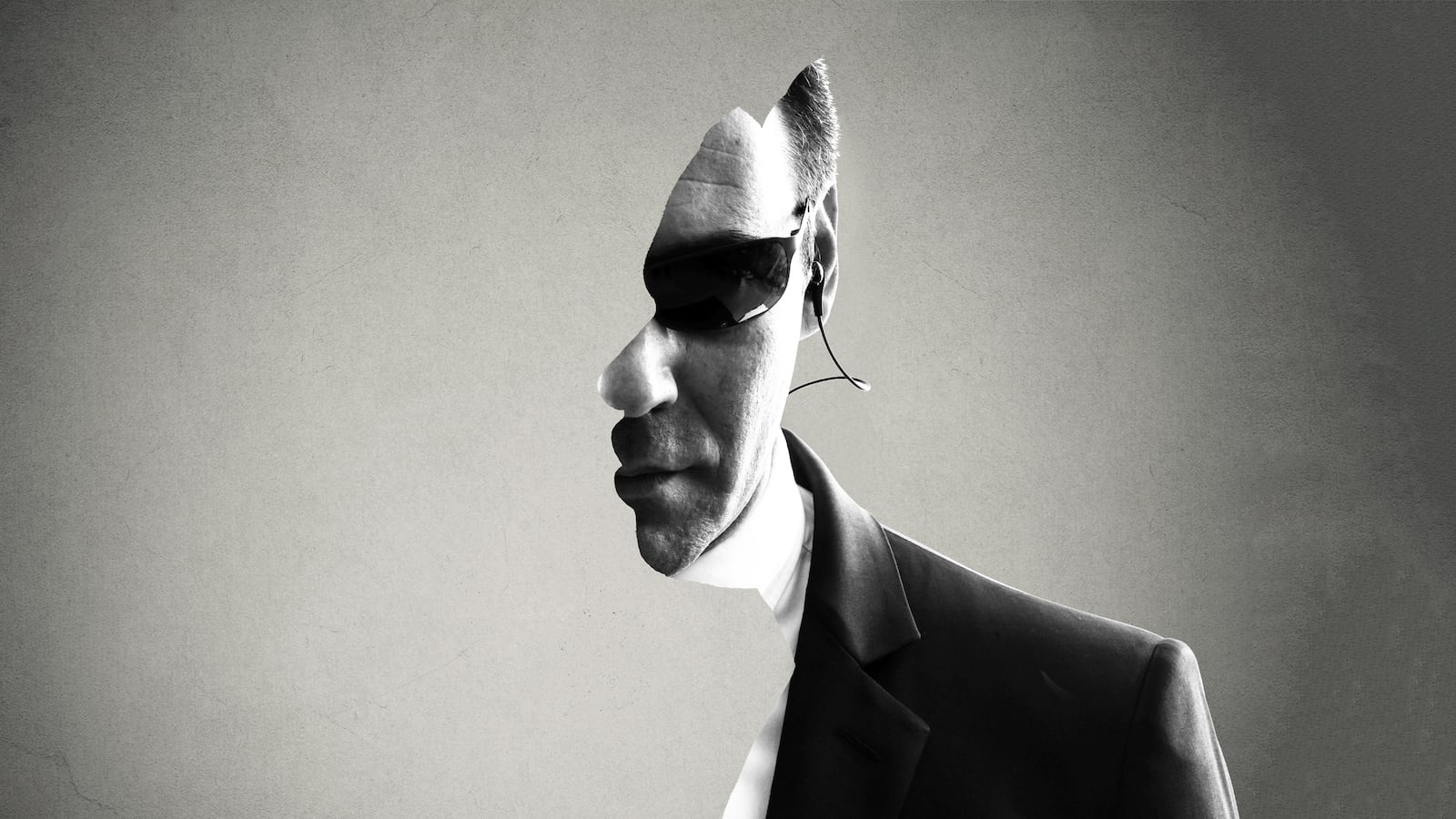

This excerpt from The Moscow Rules, which I wrote with my husband, Tony Mendez, deals with a daunting technical operation in Moscow undertaken by the CIA with support from our office, Office of Technical Service or OTS, a group often likened to the “Q” of Ian Fleming’s novels. The target was an underground communication line, newly installed, that connected the Krasnaya Pakhra Nuclear Weapons Research Institute to the Soviet Defense Ministry in the city. This newly installed communication link was accessed by a series of manholes that ran beside a heavily trafficked artery around Moscow. The problem was how to get one of our officers into one of their manholes, despite the overwhelming surveillance that we all were subjected to. The solution, from our Disguise Branch, led to a new technique that we called Disguise-on-the-Run or DOTR, and it became a tool that we used on more than one occasion. As was often the case in our line of work, our best solutions would arise out of desperation. We not only needed a technique that could ensure that our first man in would be safe, we needed a technique that could be replicated repeatedly, as our OTS technical officers serviced the wiretap once it was installed.

Here is how it began as told from Tony’s perspective:

The OTS office at 2430 E Street is still an infamous address in the intelligence community. The cluster of buildings perched on the hill behind the Bureau of Naval Medicine and across 23rd Street from the State Department, where Wild Bill Donovan began America's fledgling intelligence capability, the Office of Strategic Services, it is also where Bob Gates lived in a row of generals' quarters while he was President Obama's secretary of defense, just three blocks from the White House.

The compound consists of three buildings embracing an oval lawn—Central, South, and East Buildings. Donovan and eventually Allen Dulles had their offices in East Building. Today, with North Building demolished to build the E Street Expressway, the view is of the Kennedy Center, the Potomac River flowing down from Georgetown in the background. It was and is a historic view.

The top floor of South Building was a long, dark hall. We used this fourth-floor space as a photography test bed and a pretty clean field for path-loss measurements on our newest radio communications equipment, but today it was going to be used as a gap, a 45-second interlude in a surveillance scenario in Moscow, when I would be out of sight of my KGB surveillance team. I had 45 seconds and 45 steps to completely change my appearance. This was my chance to demonstrate to my office director what Disguise-on-the-Run (DOTR) was all about.

Dressed in a dark raincoat, dark pants, and black shoes, I was carrying an attache case and nothing else. I looked into the dim light and could just barely make out my boss, David Brandwein, director of the Office of Technical Service, at the other end of the hall. He was seated or, more precisely, slumped in a chair about 120 feet from me. Next to him was his assistant, Jonna Goeser, who was taking notes of this exercise. Her secondary job was to ensure that Brandwein did not drift off during the demonstration, overwhelmed by his narcolepsy. I had arranged with Jonna that it would not overwhelm him this morning.

I looked at my watch, the second hand just sweeping past twelve, and began to move. One step a second, 45 seconds to accomplish a complete transformation. While I had rehearsed this disguise numerous times on the streets of Washington, D.C., with our SST, it didn't mean that my adrenaline wasn't going crazy. That my breath wasn't coming too fast. That my heart wasn't about to jump out of my chest.

I stopped and positioned my attache case on the floor. Slow down, I told myself. Take it slow. Maintain a natural pace. I touched a button on the case and it popped open, transforming into a grocery cart on wheels. The attache handle became the top of the handle for the cart. At the same time, a brown paper bag inflated, and the contents, a loaf of bread and some vegetables, expanded to fill the newly available space.

I moved forward a few steps, and then I steadied the cart and began to remove my raincoat. I had to hold the tip of the sleeves tightly in order to reverse the coat; in effect, I was peeling it off, turning it inside out as my arms came out. The transformation was dramatic, as a man's black raincoat became a dark-pink woman's coat with a shawl attached around the shoulders. I slipped my arms back into the sleeves and pulled it together in front.

Pulling the cart, I moved toward Brandwein. Leaning forward, I pulled my pant legs up, first the left and then the right. A Velcro-like material caught the pants legs and held them up, revealing black stockings. A few more steps, and I reached down and removed the slip-on rubber men's shoes, one at a time, stashing each inside of my dress, each shoe becoming a female breast. Black size-11 Mary Janes were now revealed, adding more detail to the look.

Checking my watch, I saw that I was 20 seconds into the change. Good. Right on schedule. Brandwein, far from disappearing further into his sleeping disorder, was now sitting upright and appeared to be leaning forward, drawn into this performance.

As I continued down the dimly lit tunnel toward him, I reached into the pocket of the pink coat and extracted a mask that I had spent weekends creating, slipping it over my face and ever-present mustache with one hand. I reached back to the shawl attached to the coat with my free hand and pulled it up over my own hair. A gray-haired female wig attached to the shawl spilled forward, protruding from the shawl and falling slightly over my face.

Now, as I approached Brandwein, walking slowly and pushing my grocery cart almost like a walker, I saw a flash of appreciation on his face as he turned to Jonna and nodded. He knew that I had been working with unique contractors. A very special tailor in Pennsylvania who also worked for the magic industry had assembled the reversible coat, while one of our magic consultants, Will, out in Los Angeles, had developed the pop-up grocery cart.

Forty-five seconds and we were done. Dave Brandwein's introduction to our Disguise-on-the-Run Program had been a success. The businessman in a raincoat with the attache case had disappeared, transformed into a little old lady in a dirty pink coat wearing a shawl and pulling a fully loaded grocery cart. Would you be suspicious of a little old lady?

After Brandwein gave his stamp of approval, I took the technique over to headquarters to show it to Jack, who was equally impressed. Then when Jim Olson was chosen for his assignment, we brought him over to our disguise labs and began running through some scenarios.

I commissioned a quick-change, three-piece suit for Olson from our New England tailor, and he made a totally reversible suit of clothes, head to toe. It included a vest with multiple pockets and a pair of pants that would drop down from the vest with a flip of a Velcro tab. Olson could basically walk into this second set of pants. He also carried a large book made of compressed foam, actually a concealment device for some of the materials he would need to take down into the hole.

All the above would enable Olson to transform from an elegant American diplomat in a three-piece suit to a bearded Russian professor in baggy pants and jacket, carrying a book, in less than 45 seconds, even with trailing surveillance. It happened so quickly that even a casual passerby would not notice. The mask came out of his pants pocket and went on as easily as putting on a knit winter cap. All this was done while he was walking, on the move, strolling through a Moscow park and down the street along which the manholes were positioned.

Later, I would get confirmation that the disguise had worked and that Olson had been able to slip into the manhole undetected. As the first man in, it was his job to photograph the site and glean as much information as he could. Olson brought back images and diagrams of a small chamber intersected by a dozen or so lead-sheathed cables, which had been filled with gas in order to prevent tampering. The gas would pressurize the cables, which, if penetrated, would then be able to trip a sensor due to the drop in pressure.

Jim Olson was a colleague at the beginning of this disguise R&D, but by the time we had completed the work and he had rehearsed it again and again in Washington, D.C., Olson had become a friend. He is a friend to this day. Thoughtful and introspective, he brought an intellect to the deconstruction of operational problems that proved to be very helpful.

With this information in hand, the CIA was then able to move on to the next stage of the operation. During this phase, one of our techs returned to the same manhole to run tests on the wires in order to see which of the cables led to the nuclear test facility. It was a painstaking job that involved wrapping a device containing two sensors around each of the cables to sample the signals. The third and final phase involved placing the actual tap. OTS had built a kind of collar that could be placed around the outside of the cable so as to not trip up the pressurized sensors. Once installed, the wiretap worked to perfection, transmitting the intercepted signals to a recording device hidden nearby.

The operation was a massive achievement; technology and tactics came together to accomplish one of the most audacious missions ever conceived in Moscow. Here was the proof, if anyone still doubted, that the CIA had completely rewritten the rules when it came to conducting operations in the Soviet capital. There are some who have looked back on the Tolkachev operation and the CKTAW wiretap and referred to this period as a kind of golden age for the CIA. Not only were both operations massive success stories, but they had also been carried out in the most hostile environment ever conceived for an intelligence operation. It certainly appeared as if the KGB was powerless to stop us. Unfortunately, the feeling wouldn't last.

Excerpted from The Moscow Rules: The Secret CIA Tactics That Helped America Win the Cold War, by Antonio and Jonna Mendez with Matt Baglio. Copyright © 2019. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Antonio J. Mendez and Jonna Mendez, his wife, are the authors of The Moscow Rules: The Secret CIA Tactics That Helped America Win the Cold War. Mendez is a retired CIA officer who worked undercover for 25 years, participating in some of the most important operations of the Cold War. He earned the CIA's Intelligence Medal of Merit and was chosen as one of 50 officers to be awarded the Trailblazer Medallion.