Seventy years ago today the recorded voice of Emperor Hirohito announced the acceptance of the Allied terms for Japan’s surrender. While that capitulation wasn’t official until the well-known ceremony held aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, people around the world assumed that World War II was over. Then, three days after Hirohito’s tremulous announcement and Japan’s acceptance of a ceasefire, Sergeant Anthony J. Marchione—a 20-year-old aerial gunner in the U.S. Army Air Forces—bled to death in a bullet-riddled B-32 Dominator bomber in the clear, bright skies above Tokyo. The young man from Pottstown, Pennsylvania, has the dubious distinction of being the last U.S. service member to die in combat in World War II. Though tragic, his passing would be little more than an historical footnote were it not for the fact that his death came perilously close to prolonging a conflict most Americans believed was already over.

The narrative we all learned in high school regarding the way the Pacific war ended goes something like this: Japan’s armed forces had been battered into submission in the years since Pearl Harbor and Hirohito, horrified by the disappearance of Hiroshima and Nagasaki beneath roiling, radioactive mushroom clouds, defied his generals and went against generations of bushido tradition to accept the Allies’s terms for his nation’s unconditional surrender. Hirohito’s Aug. 15 announcement to his people that he had decided to accede to the terms of the Potsdam Declaration led to an immediate cessation of hostilities—except in Manchuria, of course, where those dastardly Soviets had launched a last-minute bid to snap up some Japanese-held territory—and the whole thing definitely ended with the ceremonial signing aboard Missouri.

Things weren’t actually that cut and dried, however.

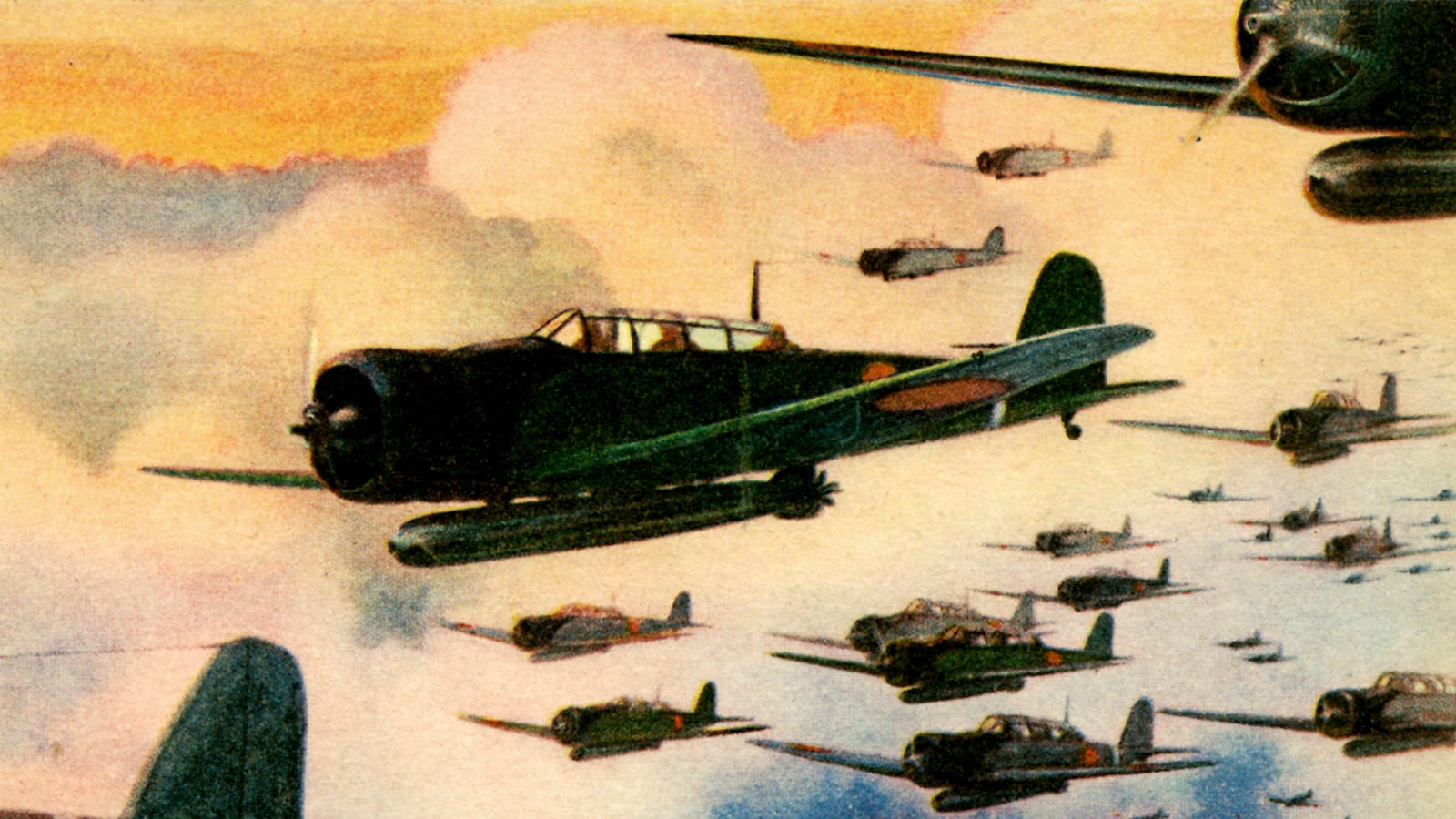

Despite the defeats it had endured and the enormous losses in men and materiel it had sustained since December 1941, Japan in August 1945 was by no means defenseless. Some 2 million men remained under arms throughout what was left of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” several thousand aircraft had been hoarded in the Home Islands for use as kamikazes, and most civilians were prepared to conduct a no-holds-barred, last-ditch defense against the almost certain Allied invasion of sacred Nippon. Planning for that two-phase onslaught, code-named Operation Downfall, was well-advanced. And, of course, there was also the very real possibility that a third atomic bomb might be dropped on Japan—most probably on the capital city itself—to further motivate acceptance of the surrender terms.

Our high school narrative holds that the massive Allied and Japanese casualties that would have unquestionably resulted from the invasion and any third atomic attack were averted by Hirohito’s Aug. 15 agreement to capitulate. A 24-hour attempted palace coup failed to prevent the surrender, and by Aug. 16 orders had begun going out from Tokyo to Japanese forces worldwide to lay down their arms, stop all offensive action and abide by the Allied ceasefire terms. Those forces—save those still battling the Johnny-come-lately Soviets, of course—heeded their divine ruler’s call, we were told, laid down their arms and prepared to accept the shame of surrender.

Again, the preceding scenario is not entirely accurate.

Though the majority of Japan’s remaining armed forces did indeed suspend combat operations on Aug. 15, two key naval aviation units just south of Tokyo did not. The Atsugi-based 302nd Air Group and the Yokosuka Air Group had been vital to the air defense of the capital region, and each counted among its members some of the nation’s most capable and highest-scoring fighter pilots. More importantly, each unit could still muster a dozen or so of the best interceptors Japan had thus far produced.

As similar as the organizations were, however, their motivations for disobeying the emperor’s ceasefire order were markedly different.

The firebrand commander of the 302nd, Captain Yasuna Kozono, was steeped in bushido and opposed the surrender with every fiber of his being. He had infused his men with the same never-surrender, death-before-dishonor ethos, and in the days immediately following the emperor’s announcement Kozono—feverish with a malarial relapse as well as burning with the humiliation of impending surrender—ordered his pilots to attack any Allied aircraft that dared to violate the nation’s sacred airspace.

The Yokosuka aviators—who included famed ace Saburo Sakai—were as proudly nationalistic as their Atsugi brethren, but far more pragmatic. They accepted the emperor’s decision to capitulate, but believed that until the surrender documents were signed, Japan remained a sovereign nation with the right to defend her airspace against enemy intrusion. They therefore decided to intercept any Allied aircraft that seemed intent on hostile action.

The man who ensured that both groups of fighter pilots would take to the air was General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. In order to confirm the Japanese were abiding by the ceasefire agreement, the supreme Allied commander in the Southwest Pacific ordered the largest aircraft in his theater—four-engined B-32 Dominators of the Okinawa-based 386th Bombardment Squadron—to undertake aerial reconnaissance flights over the Kanto Plain, the seven prefectures that make up the greater Tokyo metropolitan area.

The first mission, on Aug. 16, elicited no hostile response and the four B-32s engaged on the flight returned to base unscathed. Things turned sour the following day, however, when four B-32s sent back over Tokyo were fired on by anti-aircraft batteries and then attacked by fighters from both Atsugi and Yokosuka. The Dominators made it home with only minor damage and no casualties, but MacArthur needed to know whether the attack was a random act by rogue elements or, more ominously, an indication that the Japanese might be wavering in their commitment to surrender. He therefore ordered four more B-32s back over Tokyo on Aug. 18, though two of the aircraft turned back with mechanical problems. The pair of Dominators that reached Tokyo ran into a hornet’s nest. Repeated attacks by fighters from Atsugi and Yokosuka damaged both bombers, in the process severely wounding aerial photographer Staff Sergeant Joseph Lacharite and killing his assistant, Tony Marchione.

Told of Marchione’s death and Lacharite’s wounding, MacArthur had to make a momentous decision: If he believed the Japanese pilots were acting on orders of their government, the logical response would be to renew the aerial assault on Japan—with all the dire consequences that would entail. But MacArthur, to his credit, chose to wait. A Japanese surrender delegation was scheduled to fly to his Manila headquarters on August 19 via the U.S. airfield on the island of Ie Shima; if the two aircraft bearing the delegation failed to appear, it would be a clear sign that Tokyo was reneging on the surrender decision. If the aircraft did arrive, it would be an equally obvious indication that the attacks on the B-32s had been the work of a few diehards acting independently.

In the end, of course, the surrender delegation arrived on schedule, the Japanese government brought the various rogue military units to heel and on Sept. 2, 1945, World War II officially ended aboard the Missouri. And nearly four years later—on March 21, 1949—the remains of Anthony J. Marchione, the young man whose death nearly changed history, were finally laid to rest in the cemetery of Pottstown’s St. Aloysius Roman Catholic Church.

May he, and all his fallen comrades, rest in peace.

Stephen Harding is the author of Last to Die: A Defeated Empire, a Forgotten Mission, and the Last American Killed in World War II.