The first person to testify in the first-ever criminal trial of an American president is the former publisher of the National Enquirer. But the supermarket tabloid might not have been around to “catch and kill” stories about Trump’s sexual liaisons if it were not for the early financial support of another notorious New York celebrity, the gangster Frank Costello.

And while Trump is not known for his grasp of history, he’d do well to view Costello’s relationship with the Enquirer’s first publisher as a cautionary tale.

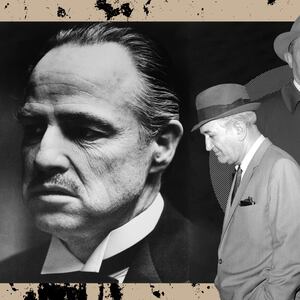

In the 1940s, Frank Costello was known as the Prime Minister of the Underworld owing to his gentlemanly public manner, political connections, and patina of respectability. Costello used the mob’s Prohibition-era millions—and the money from its vast illegal gambling empire—to take control of Tammany Hall. This meant that while Costello was the head of what came to be known as the Genovese crime family, he also pretty much ran the Democratic party in New York.

ADVERTISEMENT

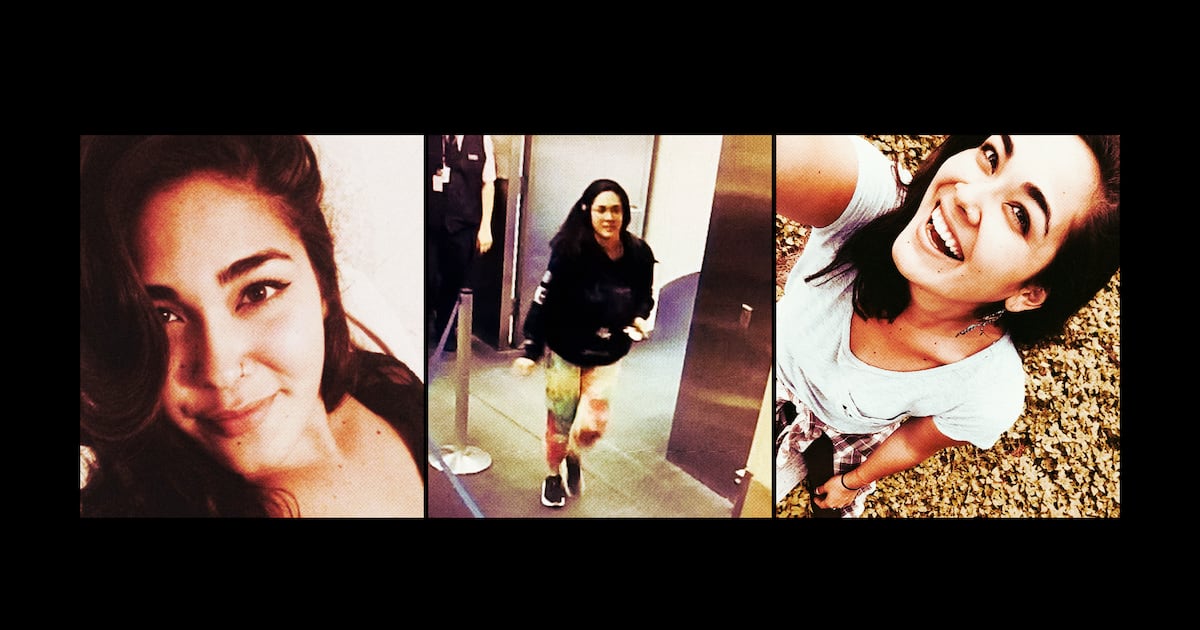

In 1942, when Costello’s godson, Gene Pope, wanted to buy the Enquirer—then called the Inquirer, Pope needed cash. Being a good godfather, Costello—depending on which source you believe—forked over somewhere in the range of $10,000 to $25,000. Costello also regularly fronted Pope the cash needed to keep the doors open at the struggling publication. And I do mean cash, because each week, a messenger from the tabloid came to Costello’s de facto headquarters, the Waldorf Hotel barbershop, where Costello handed over an envelope of greenbacks.

And just as the current Enquirer’s owner, David Pecker made sure that his publication lionized candidate Trump throughout the 2016 election and killed stories about “The Donald’s” love affairs, Pope also adjusted his editorial content to please his powerful friend. Mob-controlled politicians and businesses received positive treatment in the tabloid’s pages, and there were no stories about the Mafia’s menace and its growing power.

Pope, like Pecker, whose testimony may prove harmful to Trump, also proved to be a disloyal friend. When Costello was short on cash near the end of his life, he reportedly asked Pope to “give him “a little taste of the pie” and make him a partner at the Enquirer. Pope said no, according to Anthony M. DeStefano in Top Hoodlum, his biography of Costello, and the two men never spoke again.

But there is another, even more important lesson, for Trump in Costello’s tale, as Trump decides whether to testify in his own defense.

In l951, Costello faced perhaps the most critical decision of his life: Should he testify in front of Estes Kefauver’s Senate committee investigating organized crime in America? Costello’s many mob associates—Joe Adonis, Meyer Lansky, Tony Accardo, et al.—exercised their right to avoid self-incrimination by taking the Fifth.

But Costello did not wish to be seen as just another gangster. His governing conceit—or delusion—was that he was “cleaner than 99 percent of New Yorkers.”

Costello once said in court that he had “bundles of real important friends,” people whose names he wouldn’t share for fear of embarrassing them. And that was true.

When Costello sponsored a gala fundraiser for the Salvation Army, judges, congressmen, and political bosses found themselves rubbing shoulders with Vito Genovese and other gangland figures. Like Republican congressmen flocking to Mar-a-Lago, they came to kiss the boss’s ring.

Trump enjoys mouthing off before and after his courtroom dates. And Costello “loved to testify,” according to his longtime lawyer George Wolf. It’s not surprising, then, that Costello’s vanity got the better of him, and he decided to defend himself in front of Senator Kefauver’s committee.

While we won’t get to see Trump if he testifies, the 1951 congressional hearings were broadcast live on what was back then the brand-new medium of television. And the hearings got more viewers than the World Series. Restaurants and movie theaters—particularly in Costello’s home turf of New York City—reported a drop in business because people stayed home to watch the show. The Bonwit Teller department store—which Trump later tore down to build Trump Tower—offered late-night shopping hours once the hearings recessed for the day.

Costello’s attorney famously would not allow his client’s face to be shown on national television. This left the TV cameras to focus on Costello’s hands. As the audience at home listened to Costello’s raspy, Godfather-like voice, they watched his well-manicured hands fidgeting and folding and unfolding his handkerchief. The spectacle, which became known as the “Hand Ballet,” proved to be more embarrassing and revealing than Costello’s troubled face might have been. Eventually, Costello stormed out of the hearings—just as Trump stormed out of his civil trial in downtown Manhattan.

Costello’s reward for testifying was prison sentences for contempt of Congress and tax evasion.

And now Trump who, like his secret sharer Frank Costello, was let down by his friend at the Enquirer, might well make the same mistake as the notorious gangster whose misplaced confidence in his own unique powers of persuasion sealed his fate.