In a recent blog post, Mike Cernovich, the far-right social media personality and Pizzagate pusher, tacked another profession on to his resume: character actor.

After The New York Times ran an article in which he was briefly mentioned and described as someone not worth taking seriously, Cernovich offered a retort in his usual triumphalist style. In the blog, he rattled off a laundry list of his recent accomplishments, including the trailer for the next film he’s producing, which Cernovich asserted is in pre-production and he has promised will arrive shortly.

For the uninitiated, Cernovich has raised and contributed funds for two previous documentaries: Silenced and The Red Pill, a film sympathetic to the men’s rights movement, which netted him an an executive and associate producer credit, respectively. Now, per his blog, Cernovich has evidently decided he’s a “performance artist, fiction writer, and character actor” too.

One way to confirm if Cernovich has scored any acting gigs or dabbled in performance art would be to check the Internet Movie Database (IMDb)—the popular and massive online database of filmed entertainment.

On his IMDb page, there are no dramatic roles to be found, but in addition to the two documentaries, you’ll find that Cernovich has racked up a considerable number of producing and writing credits for his live-streamed, near-daily broadcasts on Periscope, YouTube and Facebook

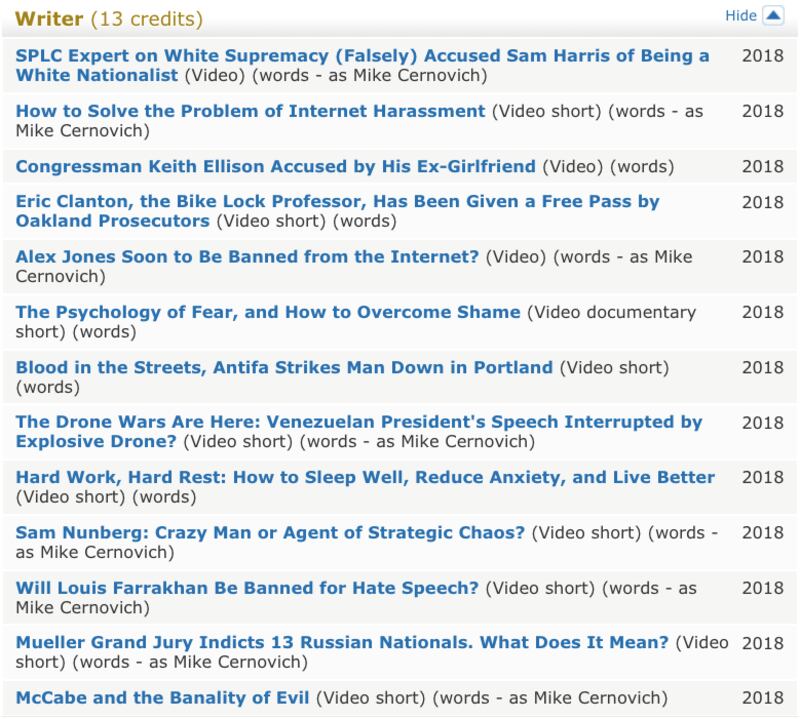

None of the “video shorts” or “video documentary shorts,” as IMDb has categorized some them, appear to have relied on a script. Still, in 2018 alone IMDb credits Cernovich as the “writer” of: “Sam Nunberg: Crazy Man or Agent of Strategic Chaos?,” “Will Louis Farrakhan Be Banned for Hate Speech?,” “Mueller Grand Jury Indicts 13 Russian Nationals. What Does It Mean?,” “McCabe and the Banality of Evil” and more, and the “producer” of close to 20 clips in the same vein.

To the casual IMDb visitor, it seems bizarre that these live-streamed broadcasts—consisting largely of Cernovich unpacking his thoughts for a camera—would be listed on IMDb at all. You know who agrees with that sentiment? Mike Cernovich.

Reached by email, Cernovich said that he has no idea how they were added to his IMDb page nor was he aware that he even had an IMDb page prior to being contacted by The Daily Beast.

“I’m chuckling here to myself, yeah, I can imagine you saw that and thought, ‘WTF,’” he said. “YouTube videos as documentaries?”

But Cernovich is far from the only online broadcaster whose IMDb page is crammed with questionable entries. While a slew of far-right hucksters and provocateurs have been kicked off various internet platforms of late, the opposite has been true at IMDb. Over the last year and a half, prominent individuals spanning the political spectrum from bog-standard conservatives to straight-up white nationalists have seen their presence on IMDb grow exponentially. (IMDb, which is owned by Amazon, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

All of the online pundits reached by The Daily Beast had the same answer as Cernovich: No. They had no part in submitting their filmed content to IMDb.

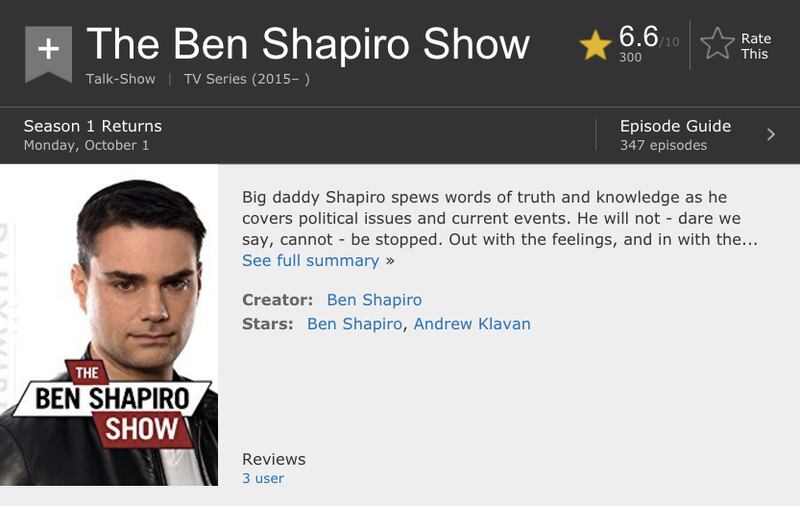

Ben Shapiro, the editor-in-chief of The Daily Wire, also hosts an eponymously-titled podcast which is also available for viewing on YouTube. Shapiro said via email that he was totally unaware he had an IMDb page until now. At IMDb, “The Ben Shapiro Show” is listed as a television series and described thus: “Big daddy Shapiro spews words of truth and knowledge as he covers political issues and current events. He will not—dare we say, cannot—be stopped.”

When asked if either he or anyone who works for him had written that description, Shapiro replied: “LMFAO.”

Like Shapiro, Charlottesville attendee and white nationalist teen Nick Fuentes hosts a podcast, “America First,” which airs five days a week. Someone, Fuentes said when reached by phone, had sent him his IMDb page in the past, but as to the material contained therein: “No, I didn’t make that at all.”

Same goes for Canadian far-right troll Lauren Southern. Her documentary Farmlands, which is available for viewing on multiple online platforms, landed on IMDb “almost immediately,” Southern told The Daily Beast via email, even though neither she nor anyone involved in the production submitted it to IMDb.

Her fellow Canadian, Jordan Peterson, the professor, best-selling author, and incel whisperer, boasts a YouTube page with close to 1.4 million subscribers. But IMDb lists one of his online lecture series, “The Psychological Significance of the Biblical Stories,” as a televised mini-series, crediting him as the show’s writer. Neither Peterson nor anyone in his employ submitted this information to the site, according to a representative.

What’s more, video shorts created by Paul Joseph Watson, InfoWars’ adenoidal editor-at-large; Scott Adams, the Dilbert creator turned Trumpist interpreter; Ethan Ralph, a pro-Gamergate blogger; Carl Benjamin, aka Sargon of Akkad, a British anti-feminist and another Gamergate alumnus; alt-right-friendly podcaster Andy Warski; white nationalist Jean-Francois Gariépy, who has been accused of trying to impregnate an autistic teenage girl; ethno-nationalist Lauren Rose; and more have received IMDb’s stamp of approval.

None of them, though, can match Stefan Molyneux’s heaving IMDb page. The former cult leader and “race realist” has accumulated close to 300 producing credits and 200 writing credits.

But if these titles aren’t being self-submitted by their creators to IMDb, who, then, is responsible, how are they pulling this off, and what does this mean for the site going forward?

Cernovich had a guess. “It was either a Cernovich super fan and great guy / gal, or someone who hates me and wants to frame me for stuffing my page,” he speculated. “Which would be pretty hilarious if the latter.”

It’s certainly a plausible theory. Still, that’s a lot of work for either a “super fan” or an antagonist, given that it’s not just Cernovich; collectively we’re talking about an untold number of IMDb entries, all of which require the submitter—or, in all likelihood, multiple submitters—to have a certain amount of knowledge about the project in order to achieve their desired goals.

That said, IMDb not only allows for third-party submissions, it is entirely dependent on them. A major motion picture alone boasts a total cast and crew that can easily reach into the thousands. If each individual working on the film were required to personally submit their own information to IMDb, the site could not exist in its current form.

To date, the site has amassed over 4.7 million titles and 91 million credits per IMDb, including projects scheduled to begin in 2025. Curating all those submissions seems like it would prove a near-impossible task. (IMDb says every project submitted via its online portal is then vetted by “IMDb title managers who will verify the existence and eligibility of the title and, if acceptable, add it.”)

Mistakes, though, have been made. In 2012, after Access Hollywood wrongly said actor James Marsden was a fan of Barry Manilow, citing IMDb as its source, a spokesperson clarified that the site makes it easy for “users and professionals” to provide corrections. All submissions are subject to “a series of consistency checks” prior to publication, the spokesperson said. Still: “Given the sheer volume of the information, occasional mistakes are inevitable, and, when reported, they are promptly fixed. We always welcome corrections."

Even so, take the trivia section on IMDb for Escape from L.A., the 1996 dystopian flick starring Kurt Russell. You have to wonder if Russell’s team personally added these entries: “Kurt Russell practiced playing basketball between scenes as he wanted to make all of his shots legitimately in the basketball scene later on. He made all of those shots purely on his own talent, even the full-court one,” and, “Kurt Russell wears his costume from the original film, which still fits after fifteen years.”

What IMDb may never have considered—and in the site’s defense, there’s no reason they should have considered it—is that people with no connection to the video shorts in question might try to game the system.

Anyone who has been driven further and further down a conspiratorial rabbit hole by YouTube’s algorithms will instantly recognize the tone, tenor, and quality of the video shorts in question. Someone logs on to YouTube, Periscope, Facebook, or all three at once, and rambles on, often for hours, about whatever the bad faith outrage-du-jour might be.

Sometimes they throw up a green screen, edit in video footage, or squat behind a desk to mimic the presentational style of broadcast news and talk shows—and in those instances, yes, there is a valid argument to be made for their inclusion—but largely they are not produced or scripted programs in any sense of the word. As Charlie Warzel noted at BuzzFeed, the low-fi standards employed by alt-lite and alt-right propagandists are part and parcel of their appeal and have helped them build up a massive platform on YouTube in particular.

And on the page detailing IMDb’s rules regarding eligibility, there’s a loophole wide enough to sneak exactly these kinds of sketchy submissions past the gatekeepers.

Per IMDb, “Online Video Content” must be of “general public interest,” [italics theirs] either for free or a fee, and not hidden on private channels. If a video short “consists primarily of footage from another title,” however, it won’t make the cut. Still, if it “displays a level of artistic merit or can be considered of public interest,” an exception can be made. Every Frame a Painting, a now-shuttered YouTube channel which analyzed the work of prominent directors, is a prime example.

That definition doesn’t read like much of a definition at all. Five years ago, Thomas Porter, who currently serves as a senior manager, database content for IMDb, per his Linkedin page, tried to break down what is and what it is not worthy of inclusion on an IMDb message board. (IMDb shut down its internal message boards in February 2017.) According to Porter, merely being uploaded to YouTube is step one. Two, despite the minimal number of views, the video passed muster because “a considerable amount of work has gone in to making it.”

Another poster chimed in, trying to pin down whether or not every clip that has ever been uploaded to YouTube would now be listed by IMDb.

“We are not interested in video clips, random camera phone footage, or many of the other bits and pieces that help bump up that 72 hours of footage [added to YouTube every minute],” Porter answered. “We are still only interested in complete bodies of work... and that is what I meant by a ‘considerable amount of work going into making it.’”

By 2017 the rate of uploads to YouTube had increased to 400 per minute. Like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous quip about pornography, it seems like IMDb hasn’t set a clear standard for how much “work” is required or what constitutes a “complete bod[y] of work” for an online video, but they’ll know it when they see it.

Reached by phone, J.D. Connor, an associate professor in the division of cinema and media studies at the USC School of Cinematic Arts, was equally baffled. “That’s insane,” he said. “That is a terrible standard.”

What’s more, the current guidelines make no mention of Porter’s insistence on “a considerable amount of work,” as one IMDb user highlighted in a 2015 message board posting. “I’m disappointed that the standards for eligibility have been lowered even further than when the floodgates were opened two years ago,” Gromit82 wrote.

IMDb’s pre-2013 policy was quite different. An online video required the presence of a “very well known” performer, be hosted by a major network, serve in some way as a “tie-in/spin” off to an already existing program, or receive a good amount of coverage by the “national, mainstream press coverage,” such as an article in The New York Times. To verify an online video’s importance and prominence, one needed to include “one or more URLs to sites other than your own.”

It’s pretty easy to see, then, how some unknown number of persons might have been able to dump a ton of right-wing filmed content on IMDb, and why, given IMDb’s own vague definitions, they’d be rubber-stamped. If it was so inclined IMDb—or rather, Amazon—could develop “robust, public standards” regarding what should and should not be included on the site, Connor explained.

But like any number of online entities that are reliant on user-submitted information. IMDb is caught in a tug of war between the need to vet content and the need to show consistent growth.

“On the one hand [IMDb] desperately needs to increase the accessibility for professionals, in order to maintain its professional data. At the same time it desperately needs to maintain its massive audience in order to remain relevant,” Connor said. According to Connor, film historians and researchers rank IMDb below TCM’s online movie database, which is far more tightly regulated and not reliant on user submissions.

Emily Best, the founder and CEO of Seed&Spark, a streaming and funding platform for independent films, often relies on IMDb to evaluate a potential collaborator, especially if it was a movie she happened to catch at a film festival. “I use it ALL the time for research, to check credentials, and to dig into production details of films,” Best said via email. (Full disclosure: This reporter worked on a play with Best ten years ago.)

As to right-wingers gaining prominence on the site: “Gross. Gross gross gross. Also, it exploits an essential weakness in this system—and one that actual creators with actual creative credits probably don’t know they could use to their advantage. (I do not bucket creators and conspiracy theorists in the same category.)”

Adam Fitzgerald, a director, filmmaker, and writer, was slightly less bullish. “The main value of IMDb, as an emerging director, is that it shows up very high in search engines,” he said via email. “It’s not going to get me a job, but it does legitimize my work a bit to be listed.”

But he largely praised the site for including online videos, given that YouTube, Vimeo, Amazon and others now provide a viable means for a young filmmaker to get a movie out into the world. While he isn’t a fan of their work, online punditry shouldn’t necessarily be excised from IMDb, regardless of his personal opinion. “IMDb clearly lists the credit as [video shorts] so anyone in the industry knows what that means. A person with 150 ‘video’ credits is not someone anyone would consider a real filmmaker,” Fitzgerald said.

“The larger issue is that the internet in general requires no fact-checking, so these nasty character-destroying videos can be made and if they go viral, there’s no coming back from them even if the content is manipulated or flat-out untrue,” he continued.

“All IMDb does is list the existence of these videos, which is largely only of interest after the fact. By the time it makes it to IMDb, the damage is usually done.”

The unknown IMDb submitters have gotten pretty good at their unpaid jobs, too. In some cases, it’s taking less than a day for a new entry to land on IMDb. For example, a Molyneux broadcast dated August 11 was on the site by the morning of August 12.

They do have a particular taste, though. Curt Schilling broadcasts on a daily basis, but his Periscope videos are not on IMDb. Similarly, Candace Owens, Lucian Wintrich, Jack Posobiec, and Laura Loomer are profligate live-streamers, but their work apparently hasn’t caught the eye of IMDb submitters. Another possibility is that the presence of prior legitimate credits, such as Adams’ short-lived television show, or Shapiro and Peterson’s numerous appearances on cable news, makes it easier to build out an IMDb page than it would be for Posobiec and his ilk.

Presumably, IMDb maintains an archive of submissions and could unmask the culprits. Or not. Until IMDb itself weighs in, it’s impossible to say for sure.

As to why someone would undertake this task, that remains a mystery. For people outside the film industry, possessing a robust IMDb page doesn’t seem like much of an asset. None of the pundits who spoke with The Daily Beast seems to care that they exist. There’s no denying the considerable audience these live-streamers and podcasters have cultivated, but if a number of their admirers were dead-set on boosting their Q-Rating, IMDb makes for a strange target.

Further, if IMDb ever does decide to enact a clear set of guidelines, as Connor said was doable, it could drastically reduce Molyneux et al.’s presence on the site. But any attempt to excise them will result in the “same kind of ludicrous overreaction” and claims of censorship which have come in the aftermath of right-wing figures being booted by other online platforms, Connor predicted.

And while Connor couldn’t identify any clear benefits to being on IMDb, “Just because I don’t see it doesn't mean that there isn’t one,” he said.

“The right is exceptionally able to capitalize on failures in the algorithm in order to put their message in front of more and more people.”