Jared and Taylor would be living an idyllic life if it weren’t for their state legislature. Their home is four blocks from their son Ben’s elementary school. (All of their names have been changed to protect their identities.) They have friends within walking distance, and Jared’s parents are just a few miles away.

“We live in a great neighborhood. We moved here right before the start of the pandemic,” Jared told The Daily Beast. “We connected with families from the school who live in the neighborhood. [...] We all had fire pits in the backyard, kids the same age. You couldn’t go anywhere, but you could have outdoor gatherings. So that’s what we did.”

Four years later, the two are considering moving again as a direct result of laws targeting LGBTQ+ youth. Ben is trans and Taylor is non-binary, and their home state is one of the states that passed laws attacking LGBTQ+ rights last year. Jared, a queer cisgender man, says the need to move became “more of a reality” for him after hostile bills passed in 2023.

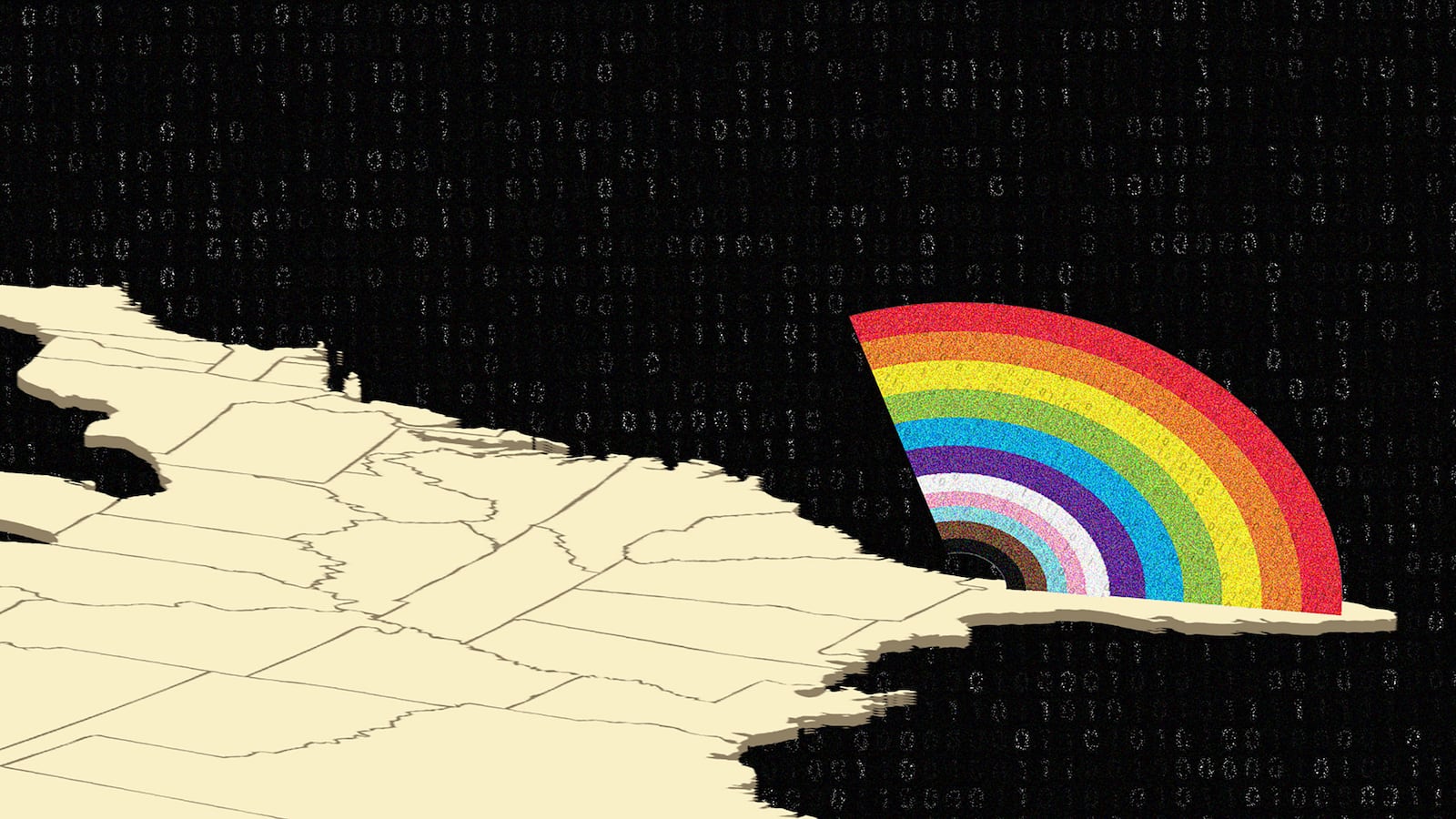

They aren’t alone: Nearly half of trans people in the U.S. have considered moving out of state in response to laws attacking their rights, according to a 2022 survey from the National Center for Transgender Equality. The ACLU tracked more than 500 bills targeting trans and LGBTQ+ people in state legislatures across the country last year, with 84 becoming law. Twenty-five of those were gender-affirming care bans, accounting for nearly a third of anti-LGBTQ+ bills passed in 2023. The attacks are continuing in 2024, with more than 400 bills attacking LGBTQ+ rights introduced by mid-February.

Jared and Taylor may need to move to protect themselves and their child, but it is a difficult decision. When they told their son Ben that they might move, he was “very opposed to it,” Jared said. That’s when Taylor found an app called InReach, which helps LGBTQ+ people find safe and affirming resources. The family has used it to find medical services and even a hair salon for their son. Ben is a drag performer, and Jared compares the love and support Ben found in the drag community to his childhood experience of church.

“Now [Jared’s youth group’s] politics would be odious, and they would not accept me as a queer man or my obviously queer family. But at the time, they gave me a place where I felt loved and supported and affirmed,” Jared said. “Ben has that in the drag community.”

Jared and Taylor face the kind of issues that arise when you have embedded your life so deeply in a community. Their oldest child, who is 24, comes to see Ben twice a week, and Ben’s best friend lives just down the street. Jared’s father lives nearby and is in “poor health,” so they don’t want to lose time with him before he passes. Jared has also lived in the state his whole life, as have generations of family before him.

“We can't remove our child from the support that they have without doing irreparable damage. And we can't keep our child in this environment much longer without doing irreparable damage,” Jared said. “There's not a good decision to make. There are no good options.”

“I do not want to relocate,” Jared added. “I desperately do not want to relocate.”

“My Heart Just Sank.”

Jared recalls the moment he knew they would need to move. He and Taylor fought against anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in their state last year, driving to the capitol to speak against the bills. When he spoke to Republican legislators, he said he “really got the impression that this wasn't something that was gonna pass.” The bills that he and his partner spoke against “were both procedurally dead” and they went to sleep that night feeling safe.

“I was on my phone, on the couch at home, feeling such a great sense of relief that, at least for now, our child was safe. And you know, I got the news on my phone,” he said. An even worse bill passed the legislature overnight. “I looked at it and my heart just sank.”

Now they use InReach to identify places where they will have all the support systems they need to not only survive, but thrive in their new home.

Jamie Sgarro co-founded InReach in his senior year of college. At the time, it was called Asylum Connect, built to help LGBTQ+ asylum seekers find safe and affirming resources while they pursued asylum status. In 2022, Asylum Connect rebranded to InReach after realizing that there were LGBTQ+ people using the app to find resources after being forced to leave hostile states for safety.

Jamie Sgarro co-founded InReach in his senior year of college. At the time, it was called Asylum Connect, built to help LGBTQ+ asylum seekers find safe and affirming resources while they pursued asylum status.

Courtesy of Jamie SgarroFor example, the number of users in Florida increased ten-fold after the passage of the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law from 260 in 2021 to more than 2,600 in 2022. Sgarro told The Daily Beast the rebrand is meant to make it clear that the app is for everyone, not just people seeking asylum.

Resources on the app are submitted by users, who rate the various doctors, lawyers, translation services, and even barbers for their LGBTQ+ friendly status. From there, trained InReach volunteers independently verify each business or group to ensure they meet the company’s standards. They also check to see if they meet criteria for intersectional support, and include tags for organizations led by BIPOC, LGBTQ+, or immigrant people, or organizations that specifically serve those groups. They also have tags related to language services, and hope to add more tags in the future.

Each organization is re-verified every six months to make sure they still meet the requirements. Sgarro said they encourage people to submit resources to InReach, even if they aren’t planning on using the app to find resources themselves, because the organization relies on those personal recommendations to expand the list of services for their users.

InReach is particularly proud of what they said were “thrive” resources, not just “survive” resources. They make a point of adding community organizations, including those related to “social groups, cultural centers, pride centers, or spiritual support,” but also “art, music, literature, sports and entertainment” in addition to legal, medical, or mental health resources.

Resources on the InReach app are submitted by users, who rate the various doctors, lawyers, translation services, and even barbers for their LGBTQ+ friendly status. From there, trained InReach volunteers independently verify each business or group to ensure they meet the company’s standards.

InReachJennifer, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, is a queer social worker and therapist in an affirming state. She previously volunteered at InReach and told The Daily Beast that she now uses the app to help find support services for her clients if they have to move for work or family reasons.

“The app has been instrumental in making sure that no matter where the person is moving to they have some resources,” Jennifer said. She gives people a list of service providers they are looking for and has them install InReach themselves.

Starting a Trend

Family Equality, an organization that advocates for equal rights for LGBTQ+ parents, is working on their own app for a similar purpose. President and CEO Jaymes Black told The Daily Beast that the catalyst was a single mother who got in touch with the org after she fled her home state to protect her trans child.

“She drove 20 hours just to get to safety, just to save her trans child, because of legislation. When we heard that, we knew it was not the last time we would hear these kinds of stories,” Black said.

Family Equality and InReach are currently in conversation on how to make sure they support each other and don’t waste time duplicating each other’s work. Black said the most significant part of their application, which will be named “Path2,” will give comparisons of school environments and state legislation, as well as drawing on the state equality scores created by the Movement Advancement Project, to allow people to make state-by-state comparisons.

As a Black genderqueer mother, Jaymes Black knows how dangerous a hostile state can be for queer Black families. Their family moved away from Texas after their children started to hear more hostile rhetoric from their peers.

Jaymes BlackAs a Black genderqueer mother, Jaymes Black knows how dangerous a hostile state can be for queer Black families. Their family moved away from Texas after their children started to hear more hostile rhetoric from their peers. “When you insert the legislation on top of [being Black], when you insert the rhetoric coming from governors and other state leaders, that trickles down to the community,” Black told us, explaining why their family left Texas.

Anti-LGBTQ+ legislation can also threaten immigrant families. Cynthia Garcia, co-director of organizing and training at United We Dream, told The Daily Beast that when immigrant youth seek gender-affirming care in hostile states, it can lead to investigations into their family. From there, it “creates an immediate door to a deportation pipeline,” she said.

Jared said that InReach “makes it possible” to find where they can move and find safety. Without it, there would be no way to find neighborhoods with the resources they need to not only survive, but thrive again after moving. Taylor, who described themselves as “a Virgo to a fault,” has created a relocation matrix in a spreadsheet, which lists everything they will need nearby when they move.

They can use the tags in the app to check for resources available in a city or state, which helps them find places where their family can safely build community without sacrificing any of their medical needs. Still, Jared wishes they didn’t need InReach. “It’s good to know that it exists. But it would be a whole lot better if it didn’t have to.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated with Jaymes Black’s correct title and the correct name of the app.