BOSTON—As Scott Strode walked through the maze of South Boston traffic islands and warehouses near his newest gym, he pointed down to a discarded syringe on the ground.

“Just watch the open-toed shoes,” he warned.

The needles are part of the landscape here, on the south side of the city. So too are the orange caps that were once perched on top of them but are now scattered over the cracked concrete. There is little to no foot traffic, just the junkies who come next to the McDonalds to shoot up, including one man that early June day in a black tank top who writhed on the ground near the drive-thru.

And yet, this is where Strode and his colleagues decided to set up shop.

That was always part of the plan. Strode is a recovering addict himself. And he knows that in order to provide effective recovery treatment, those who are recovering physically and emotionally need to be able to actually get there.

“On your recovery journey, when you get sober, overnight you lose your identity even if it was a negative identity and you have to fill that with something else or it’s easy to fall into that old pattern,” Strode said. “We wanted to be in places where we are accessible and a lot of people in recovery, transportation is a huge issue.”

Strode is the executive director and founder of the Phoenix, a network of gyms that specifically targets those seeking recovery. He has facilities in 10 states and 13 cities. The one in South Boston is his latest project: a mammoth warehouse devoted to personal betterment. It is still barebones. But when it opens in September, it will feature weights and treadmills, a climbing wall and a yoga room. It is clean and organized, with red, white and gray paint on the interior and a neat line of clothes donated from the lost and founds of other gyms to help those who don’t have, or can’t afford, workout attire of their own.

Unlike those gyms, however, this one is in a less-than-bustling location. Strode’s latest Phoenix is on the so-called Methadone Mile, the nickname of the cluster of methadone clinics offset by open air drug markets in the shadow of Boston University Medical Center and their busy ER. The gym will cater to people who are recovering from addiction by creating a healthy and accepting community where they can find the strength stay sober. Membership is free. All an individual needs is 48 hours of sobriety and to agree to the “code of conduct.” Strode and his colleagues take care of the rest.

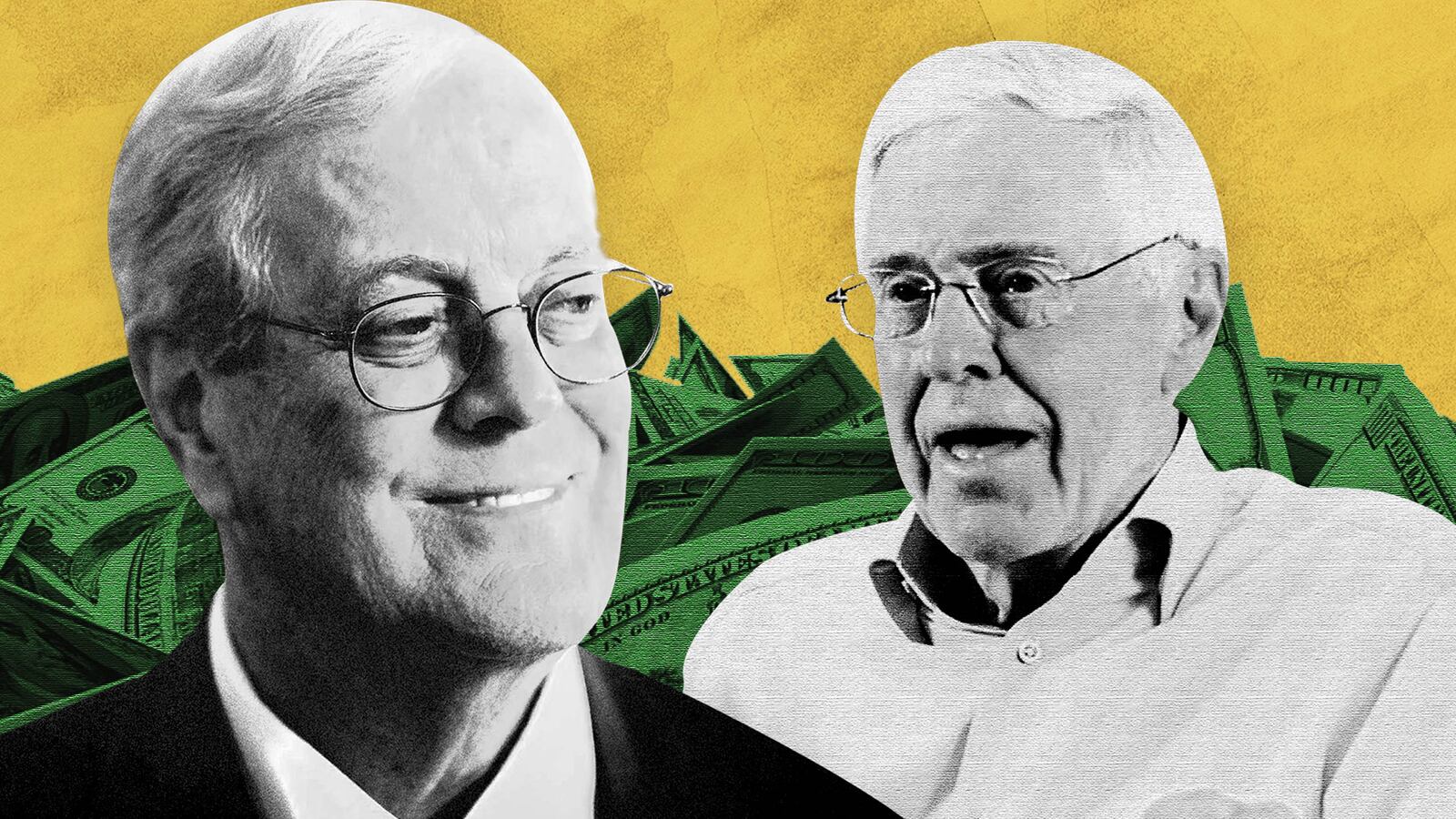

It’s an ambitious, out-of-the-box idea towards tackling a crisis that is crippling neighborhoods across the country. And it’s one that’s caught the attention of some important, and controversial, financiers. Since 2016, Strode’s gyms received a $3 million investment of the conservative Koch Brothers, as a part of a multi-year plan to help him expand to other cities and replicate the community-based addiction care.

The Koch funds are part of their Stand Together program, which launched in January 2016 with the goal of funding community-based solutions led by “social entrepreneurs” to systemic poverty problems. The program, staff said, aims to help fill the void where they believe the country has left through ineffective programs that ignore community-based solutions that can actually lead to change.

“Our country has failed on this front,” said Evan Feinberg, the executive director of Stand Together. “The government solutions are not working. The government's very significant commitment to try to address this crisis, while well-intentioned, has really been counterproductive when you look at Methadone Mile.”

Stand Together and the Seminar Network—the broader organization of the Koch entities—is an example of parts of the Koch network that are moving away from partisan politics and more more towards investment in other avenues.

The Kochs, of course, haven’t stopped pursuing their agenda through elections. But in recent weeks there has been a noticeable shift in their strategy. The network ran a positive ad for North Dakota Democrat Heidi Heitkamp after she supported bank deregulation legislation. And Americans for Prosperity—another Koch-backed group—deciding to stay out of the Virginia Senate race after far-right wing Republican Corey Stewart won the GOP nomination.

Since it launched in 2016, Stand Together has created 86 partnerships with community-level groups “to help people living in persistent poverty to remove barriers and improve their lives,” according to Feinberg. The Phoenix was one of the first and largest investments the group has made to date.

“The Seminar Network and Stand Together believe the best solutions do not come from the top down or from experts that think they have all the answers, but instead from social entrepreneurs like Scott Strode and The Phoenix who are using local knowledge and an innovative approach to help people overcome substance use disorders,” said Feinberg.

Strode co-founded the first Phoenix in 2006, with the idea that those in recovery would feel compelled to stay sober if they felt that their days had been spent bettering both their minds and their bodies with others who understand their challenges and back them up. He said the Koch program helped him begin a rapid expansion not only of brick and mortar gyms but also of Phoenix Rising, a program that would allow individuals to start their own gyms in their own communities.

“I’m a big believer of also that sort of what’s coming out of DC even over the last 10 years, really 15 years, 20 years, isn’t really getting at the root of this issue,” Strode said. “We have overdose reversal drugs, we have more treatment beds, we keep adding that stuff and the crisis continues to get worse.”

Strode often wears a black t-shirt with the word “Sober” in large red letters that stretches across his barrel chest. He is does not look the part of your prototypical executive. But KoKhis impact is vast. Since opening their doors, 26,000 people have been served by Phoenix gyms, with a relapse rate of 23 percent, according to Strode. That’s compared to a relapse rate of more than 50 percent in more traditional treatment centers.

The Boston gym will open officially this fall. But on any given day it has dozens of attendees who come to lift weights, do crossfit, and work out with trainers who are also in recovery.

Lee Soares is one of those trainers. He has a tall, muscular, intimidating appearance that is offset by bright purple sideburns. Soares decided to get help after he found himself on his two bottles of whiskey in a graveyard, practicing knots for a noose.

“I was figuring out what tree I was going to throw the rope over and I get a phone call and it was my friend, John and he had heard I was in trouble,” he said. “He said ‘I can get you help,’ just hearing those words changed everything.”

Soares entered a more traditional treatment recovery program and eventually found his way to Phoenix. More than three years after that night in the cemetery, he wears a black rubber bracelet with the words “tough shit don’t drink” and says his path as a recovering addict has made him a better, more empathetic coach to others.

Strode has watched the opioid epidemic grow firsthand both through the foot traffic in his gym, and through his social media and email accounts.

“It can be overwhelming the number of loved ones that reach out to us, wanting Phoenix in their community,” he said. “They basically say, ‘I feel like Phoenix could help my loved one if we could just get them to you or they say, I know that Phoenix would have helped my son or daughter.”

Prior to the Koch investment, Strode said the gym was overwhelmed by requests to help individuals caught up in the opioid crisis. He recounted how one woman reached out to offer money to help fund a gym in her town in the hopes of saving her son. But by the time they got there, he had overdosed.

“We were trying to meet that need but the scale and organization quick enough to meet that need and make it sustainable is really hard,” he said.

Strode said that the gym has received a collection of government grants over the years but described the funding as “whimsical” and prone to the changing fancies of whatever party is in charge.

“I think that at a policy level we have to look at innovative programs. We have to put in place things that protect folks from stepping into do it in the first place and I think it would be easy— prescription drugs is a faucet we can turn it off,” he said. “Dentists are prescribing drugs that used to be end of life drugs—to manage pain at the end of life from cancer or something like that. Now you can get 15 days of it if you get a tooth pulled.”

He added, “I think we need to look at that whole system and look at how pharmaceutical companies can capitalize on addiction and people that make drugs that put us on to this stuff are making drugs to take us off of it - there’s not a solution in there. We are going at it with tactics, not a strategy.”