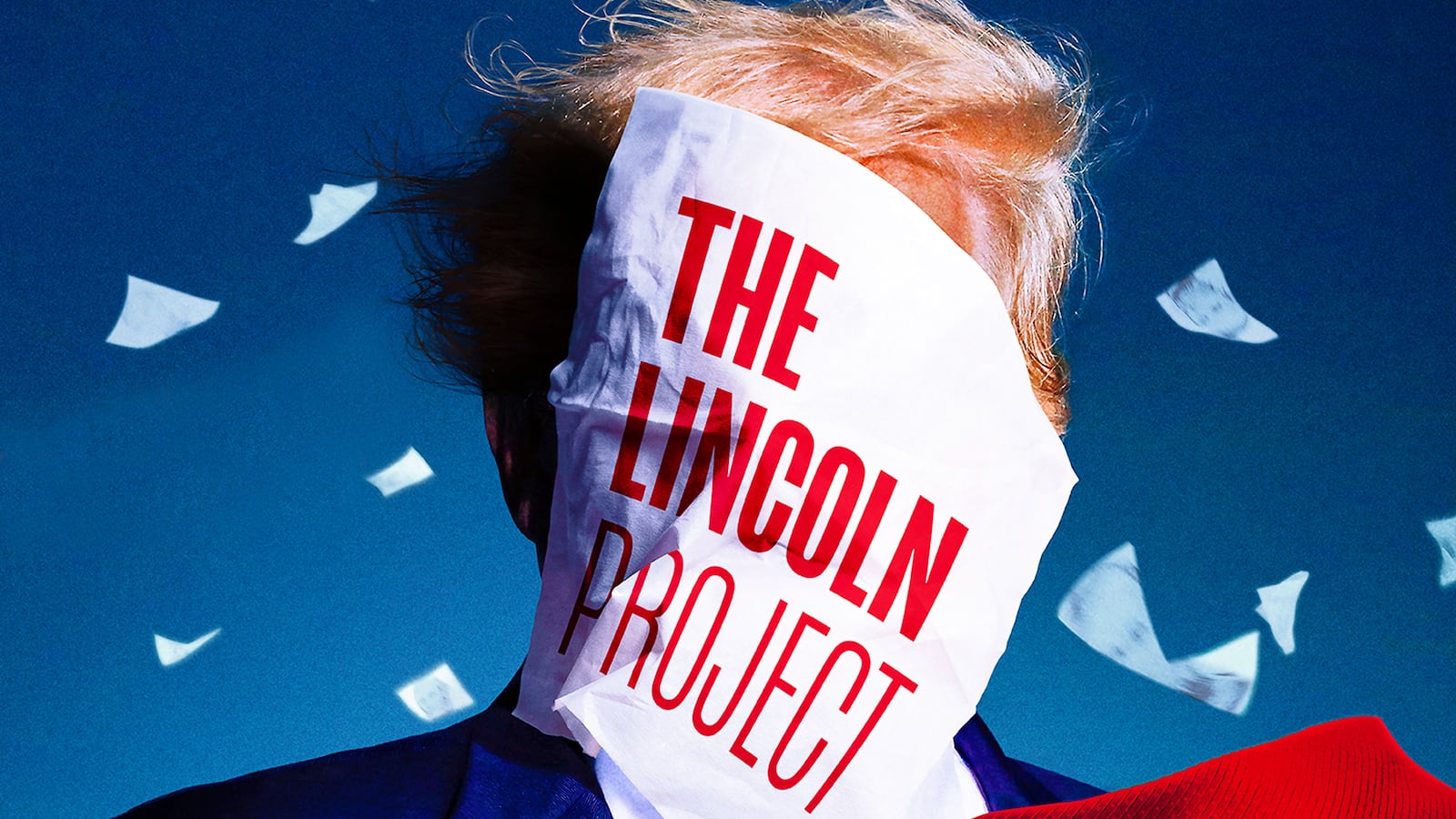

The Lincoln Project, the super PAC created in late 2019 to help defeat Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election, is one of the largest trolling operations in modern human history, designed to alter the country’s political future by getting inside—and thoroughly screwing with—the commander-in-chief’s head.

Formed and led by disenfranchised big-time Republican consultants and strategists, it produced viral ads that took the fight directly to Trump. Thanks to its blistering attacks, it became a hit with those on both sides of the political aisle, although its stratospheric ascent was interrupted by a series of bombshells that called into question the motives, and character, of the men and women behind it. Far from a feel-good fable, it turned out to be a more complex tale about activism and avarice, nobility and self-interest, loyalty and betrayal, success and scandal.

As co-founder Steve Schmidt admits, “Make no mistake: the idea that the Lincoln Project story is the story of the good people against the bad people is a very naïve take on this.”

The Lincoln Project is that warts-and-all saga, told in up-close-and-personal fashion by directors Karim Amer (The Vow) and Fisher Stevens. Immersing themselves with the group from early September 2020 (two months before the election) to February 2021, the duo’s five-part docuseries—premiering Oct. 7 on Showtime—is a multifaceted fly-on-the-wall portrait of 21st-century politics and the many gambles, compromises and duplicity it entails, all filtered through the experiences of those at the helm of the Lincoln Project. That leadership unit was announced in December 2019, and included Schmidt, George Conway, Rick Wilson (a former Daily Beast contributor), John Weaver, Jennifer Horn, Ron Steslow, Reed Galen, and Mike Madrid. All of them played key roles in the organization’s subsequent rise, even if this non-fiction account suggests that the four who were really running the show were Schmidt, Wilson, Galen, and soon-to-be-member Stuart Stevens.

At least at the outset of The Lincoln Project, such distinctions don’t seem to really matter—everyone receives an honorary “co-founder” title and are equally dedicated to their “psych-warfare campaign” against the president, whose mission is summed up by Rick Wilson: “We’re here to kick the shit out of Donald Trump.” What made the Lincoln Project unique was that this collection of disaffected Republicans were all veterans of various nasty political campaigns and had expertise in manipulative messaging and media, and thus boasted the specific skillsets required to be a thorn in Trump’s side. Consequently, it wasn’t long before their “Mourning in America” spot stoked the ire of the president, whose tweet about the group transformed it into an overnight sensation, helping it raise tens of millions, expand its staff, and become a hydra-like machine that poked the Trumpian bear in real-time on social media, developed popular commercials, and then—courtesy of Mike Madrid’s data-oriented team— strategically place them in the markets where they would have the most real-world success at pushing voters toward Joe Biden.

For many liberals, the Lincoln Project was a “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” sort of collective, comprised of some of the Republican Party’s most dastardly operators. Wilson, Schmidt and Stevens don’t mince words in The Lincoln Project about their less-than-savory past exploits and mistakes, highlighted by Schmidt’s regret that he was the chief presidential campaign advisor who recommended that John McCain choose Sarah Palin as a running mate—a decision (“Biggest fucking mistake of my entire life and that I will regret until the day I die”) that now looks like a tipping-point moment for the Republican Party toward fascism. Stevens admits that the Lincoln Project is a chance to oppose a “morally bankrupt” and “white grievance”-obsessed right-wing movement that he spent his life helping to create, and that sentiment is echoed by many involved, who view their new venture as a means of fixing the very things they broke.

While the Lincoln Project portrayed itself as noble, its conduct turned out to be less so. The Lincoln Project eventually becomes a story about greed, abuse and treachery. Co-founding member John Weaver—who’s rarely seen in the docuseries, ostensibly because he was recovering from a heart attack at the time—is accused of sexually harassing and grooming dozens of men, including one who he started talking to when the kid was just 14, and accusations fly that the other co-founders covered it up. Reports emerge that $27 million in funds were transferred to Galen’s Summit Strategies firm, possibly to be used for a post-election media company that Galen, Stevens, Schmidt and Wilson were looking to create. Angry charges of grifting and massive in-fighting ensue, leading to the departures of Horn, Steslow, Madrid, and valued executive director Sarah Lenti.

The Lincoln Project mires itself in this turmoil without opting to take overt sides; Horn, Steslow, Madrid and Lenti (as well as staffers with first-hand experience of Weaver’s criminal behavior) get plentiful opportunities to rail against their colleagues’ decisions, just as Wilson, Galen and Schmidt are granted chances to hit back at the allegations leveled against them. There’s a no-holds-barred quality to the directors’ later episodes, which is fitting for an outfit that wanted to take the gloves off against the president, and the directors ultimately let viewers decide who to believe. The bigger questions—about the primary role of money (and money-making) in politics; about whether right-wing agents can be trusted to wage war against their former party; about the need to get in the mud when combatting the lowest of the low; and about the tangled web of altruism and selfishness that drives so much of contemporary politics—remain similarly up for debate, all as the Lincoln Project’s compromised circumstances come into clearer view.

As a result, The Lincoln Project proves a case study of a phenomenon marked by both virtuous pro-democracy goals and various individual and internal failures. Whether its good outweighed its bad isn’t something Amer and Stevens choose to explicitly weigh in on, but what’s hard to dispute is Stuart Stevens’ warning that—with fascist Trumpism still flourishing even after the 2020 election and Jan. 6—“the greatest danger of what we’re in now is not realizing the greatest danger.”