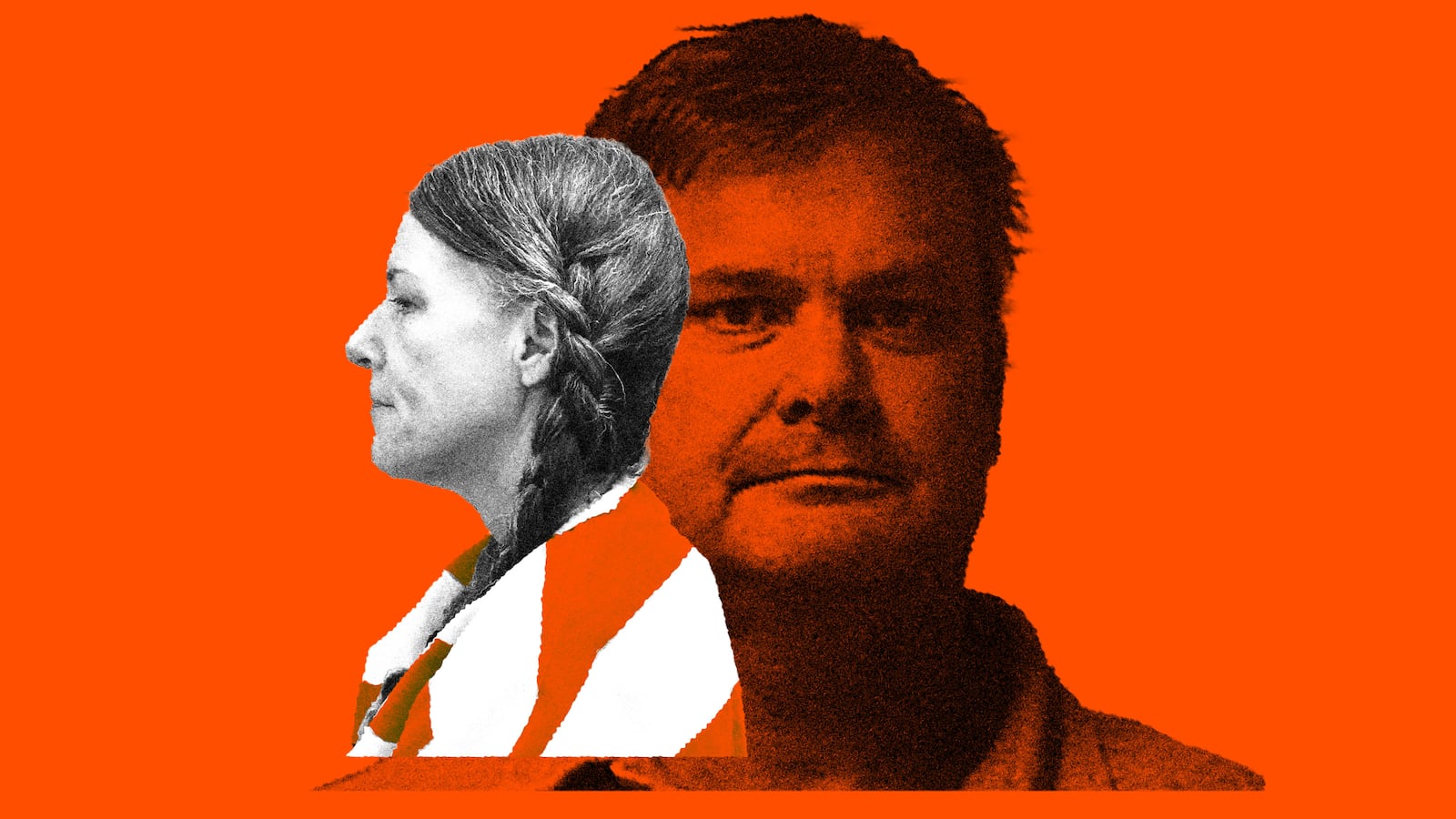

On the warm summer day when Lori Vallow learned she would spend the rest of her life behind bars for killing her children, it was one kind of conclusion to her years-long saga, but hardly the real end of the story.

By then, Vallow’s story had been tumbling forward in the public eye for more than three years. It was a tale of a wild and salacious affair that instantly had true crime junkies and online sleuths foaming at the mouth: the devout Mormon mother who scurried off to Hawaii under cover of night with Chad Daybell, a self-proclaimed visionary and well-known author of apocalyptic novels. They believed they were godly warriors who had been married in past lives. The pair vanished just after police in Rexburg, Idaho arrived on Vallow’s doorstep asking questions about the whereabouts of her 7-year-old son, JJ. She smiled and tossed her hair and claimed it was all a big misunderstanding, and then she was gone in the dark: disappeared before anyone knew yet that her daughter, 16-year-old Tylee, was also missing.

It took months for authorities to understand the size and scope of Vallow’s intricate web: there were the two missing children, but soon more violence became clear. There was the strange case of Daybell’s wife: a cheery elementary school librarian who went to bed one night and never woke up. There was Vallow’s dead fourth husband: shot to death in Arizona. There was Vallow’s dead third husband: a man she reviled and whose body rotted in his apartment for days before anyone found him. There was a drive-by shooting. There were the strange “casting” meetings where faithful women would hold hands with Vallow, summon the elements, and pray for the deaths of their enemies.

When police finally did track down the thin, flaxen-haired Vallow, she was lounging in a blue bikini and oversized sunglasses by a swimming pool in Kauai, Hawaii, languidly thumbing through the pages of a book about near-death experiences that is popular among the fringe of the Mormon church. She looked up from its pages, annoyed at the interruption. By then her own kids were dead, buried months prior in deep holes in Daybell’s backyard in Idaho. She was on vacation.

That poolside scene was telling. Pretty and religious, no one had ever suspected Vallow had a bad bone in her body. She was the embodiment of wholesome and clean, and even the people around her were reluctant to cast a cold eye on her radical religious beliefs. When she spoke of dark spirits, zombies, portals and psychics, they simply listened. Few batted an eye when she told them Jesus had appeared before her, and meant it literally.

We are taught in America to revere those who are devoutly religious, and navigate carefully around the words of the god-fearing, to have respect and never question the intentions of those who are faithful. But throughout Vallow’s trial, one sentiment came up again and again: She always seemed so kind, so faithful. Could a believer really think God made them kill? It became clear that the only the faithful people around her, who knew the strange doctrine she preached was forged in extremism, could have stopped Lori Vallow’s trail of dead.

It’s important to understand that Vallow justified violence with an extreme interpretation of the LDS faith, and she was not the first: in 1984, Dan and Ron Lafferty spilled the blood of their sister-in-law and infant niece, believing God told them to do so. In 1978, the wife of a man who believed himself an LDS prophet marched her children one-by-one off a Salt Lake City, Utah balcony, where all but one fell to their deaths.

Killing is hardly the only criteria for extremism: by the time of their arrests, Vallow and Daybell had made names for themselves among a subset of far-right Mormon believers who think their faith makes them God’s chosen people, and that America is God’s chosen land. And in the summer of 2023, it was that very world that slowly slid out of the fringe and—quite chillingly—into the mainstream.

It started at the box office.

On July 4, the action movie Sound of Freedom hit screens nationwide telling a fictionalized version of the life of Tim Ballard, an LDS man who long ran Operation Underground Railroad, a nonprofit devoted to saving children from sex-trafficking. The film was like bait dangled over the heads of Q-Anon believers, ready to gobble up anything that proves their worldview: that this is a world filled with elite sex traffickers who snatch up children in order to harvest their blood. Sound of Freedom proved hugely popular, grossing hundreds of millions in less than three weeks in theaters.

Ballard’s backstory was, of course, more complicated. His star rose in one particularly Mormon circle: a set of conferences that push a take on the LDS faith that prizes both personal revelation and mysticism, all with a constitutionalist bent. They are the kinds of events where astrologers and energy workers stand on stage next to hyper-conservative preppers and alternative historians, appealing to believers who want to level up their faith.

From conference to conference, the agendas are filled with teachings the LDS hierarchy in Salt Lake City have warned are dangerous, and a threat to the faith. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, headquartered in the Utah capitol city, relies on a stringent leadership pyramid where only the men at the top—the president and the men of the Quorum of Twelve—can voice the teachings of God to the entire faith. Anyone else who claims to be able to do so is an apostate.

The same ecosystem that gave Ballard prominence also did the same for Daybell and Vallow. On the occasions that Ballard was a featured speaker at a conference called FIRM Foundation, he appeared alongside anti-government activists and people who push a version of American history where the founding fathers consulted the Book of Mormon. (There is no evidence of this.) Many of those same speakers, and attendees, hopped from one conference to the next. For several years, a set of conferences called Preparing a People highlighted many of those same people. They gave the mic to Chad Daybell, who wrote apocalyptic novels that he claimed held visions of world collapse that had been shown to him by God. It was at one of these conferences where he met Vallow, a fan of his work. He told her they had been married in a past life. Their fateful union began.

As Sound of Freedom played on silver screens, Ballard’s star seemed to keep rising. There was talk of him running for Senate after Mitt Romney, the prominent Utah senator and Mormon, said he wouldn’t run again.

But before summer was over, Ballard crashed back to earth. Vice News, which had been reporting on the man for years, broke the story that he had been quietly placed on administrative leave by Operation Underground Railroad over allegations that he had sexually abused women. In September, an attorney representing Ballard’s accusers said he subjected several women to “sexual harassment, spiritual manipulation, grooming and sexual misconduct.” In a lawsuit, the women alleged that Ballard told them he had been married to them in past lives. It was Chad Daybell all over again.

History is filled with powerful men denying that they ever harmed anyone, and continuing to rule. The hyper-conservative people who lionize Ballard and believe a Q-tinged worldview might have simply ignored such allegations. But what they couldn’t ignore were the rare words of the LDS Church leaders, who issued a statement condemning him. To ignore the church in favor of Ballard meant to turn away from God.

Tim Ballard had miscalculated when he spoke casually of his close friendship with one of the LDS church’s leaders, named Russell Ballard—a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles (who has the same last name, but bears no relation). By doing so, he sealed his own fate, committed the ultimate error. The condemnation that followed was swift and total. Deseret Book—the church-operated bookstores—removed his myriad works of revisionist history from its shelves. Later, Vice revealed that Ballard’s so-called missions to save children had been directed by a psychic. It was news that was only shocking if you never paid any attention to that ecosystem where Ballard and Daybell had found so much footing.

The historian Benjamin Park told the Salt Lake Tribune’s “Mormon Land” podcast that the furor over Ballard proved Operation Underground Railroad “was more of an ideological project than an actual practical one.” Everyone can agree sex-trafficking of any human is horrible. But Ballard’s work was about pushing a conspiratorial worldview forward. It was about revising history, making it more religious and god-tinged.

And yet still, in the wake of Ballard’s collapse, many people cried out that they believed Tim Ballard, not Russell Ballard—the leader supposedly appointed by God. “Did that surprise you?” Peggy Fletcher Stack, of the Tribune, asked Park on the podcast.

“You want to assume that people aren’t reading religion through a political lens,” the scholar answered. But “the signs have been marked all along, whether we want to see them or not.”

This was the season that proved why it was wrong-headed to see the story of Lori Vallow and Chad Daybell only as a murderous love affair, to relegate it to the world of true crime. It was the summer where the fringe world that created them jumped from the edges of the LDS church to the mainstream of America, and into the hearts and minds of people with Christian Nationalist views.

In many ways, Park’s words were prescient for a spreading virus: that people can hear truth and still choose not to believe it.

This has long been an issue for Mormonism. The faith’s history is riddled with schismatic groups led by people who were at odds with what church leaders told them was true, and claimed, instead, to be the new keepers of God’s word. Some broke away to practice polygamy. Others broke off to be able to become their own prophets. This continues.

In late October, a different blonde Arizona mother with doomsday beliefs was in the news. Spring Thibaudeau, who resided in the same Phoenix suburb as Vallow, suddenly disappeared with her 16-year-old son, who she believed was the “Davidic servant.” Family members said that the woman had grown increasingly obsessed with the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, soaking up the writings of doomsday authors. Court documents filed by the boy’s father said Spring had “started forming beliefs in end of the world scenarios, eerily similar to the well-publicized Lori Vallow and Chad Daybell saga.” A frantic search ensued through Idaho and Canada; after days of searching, the woman, her brother, and the boy were located at the Alaska border.

But not all doomsday ideas have been at the edges of the church. At times, that fringe thought has been in the heart of the faith. It can be easy to cast aside Ballard and Daybell and Vallow as breakaway rogues; what is harder to weigh up is the way, for decades, some of the top leaders of the Mormon faith have sowed a paranoid worldview that braids faith in God with Americanism. As Christian nationalist ideas continue to become entrenched in a deeply divided country, now would be as good a time as ever for the leadership of the church to reckon with this past and push away these ideas.

Last year, the Pew Research Center published a report that found that most American adults believe the Founding Fathers intended for the United States to be a Christian nation. This mentality is being echoed from some of the most prominent Republicans in the country. In a 2022 speech, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is running for president, told listeners to “put on the full armor of God. Stand firm against the left’s schemes.”

“You will face flaming arrows,” he said, “but if you have the shield of faith, you will overcome them.” It was the same kind of warrior rhetoric that Ballard uses, and that Daybell wrote about in his books. And yet, this time, it was mainstream.

Next spring, more chapters of the Book of Daybell and Vallow will conclude. He will face a jury for murder and conspiracy. She will be extradited to Arizona, where she is accused of a host of other crimes. It could be years before all of the legal proceedings in the case conclude, and even when they are over, nothing about their story ends until the wider LDS culture stops casting the pair aside as fringe freaks of the faith, but extremists who were coddled in their midst.

Leah Sottile is the author of the book When the Moon Turns to Blood: Lori Vallow, Chad Daybell and a Story of Murder, Wild Faith and End Times.