A searingly simple request came from one of the Mexican Marines who were invited to visit New York after they captured El Chapo.

“Do you mind if we walk around for a while?” one of the Marines asked a senior U.S. federal agent who was hosting them. “I can never do this in my own county.”

The host agreed, and the 15 or so Marines ambled through the streets of Manhattan in peace and safety none of them could enjoy back home.

For to be a Marine in Mexico is to be marked for death as a member of the most incorruptible, resolute and courageous force opposing the cartels.

Further proof of that came just two weeks after their New York City stroll, when one of these same Marines became the latest to die in the Mexican drug war.

His comrades had to guard against what happened after the funeral for another Marine just before Christmas in 2009. That fallen comrade’s family had just returned from the burial when cartel gunmen burst in and shot them all.

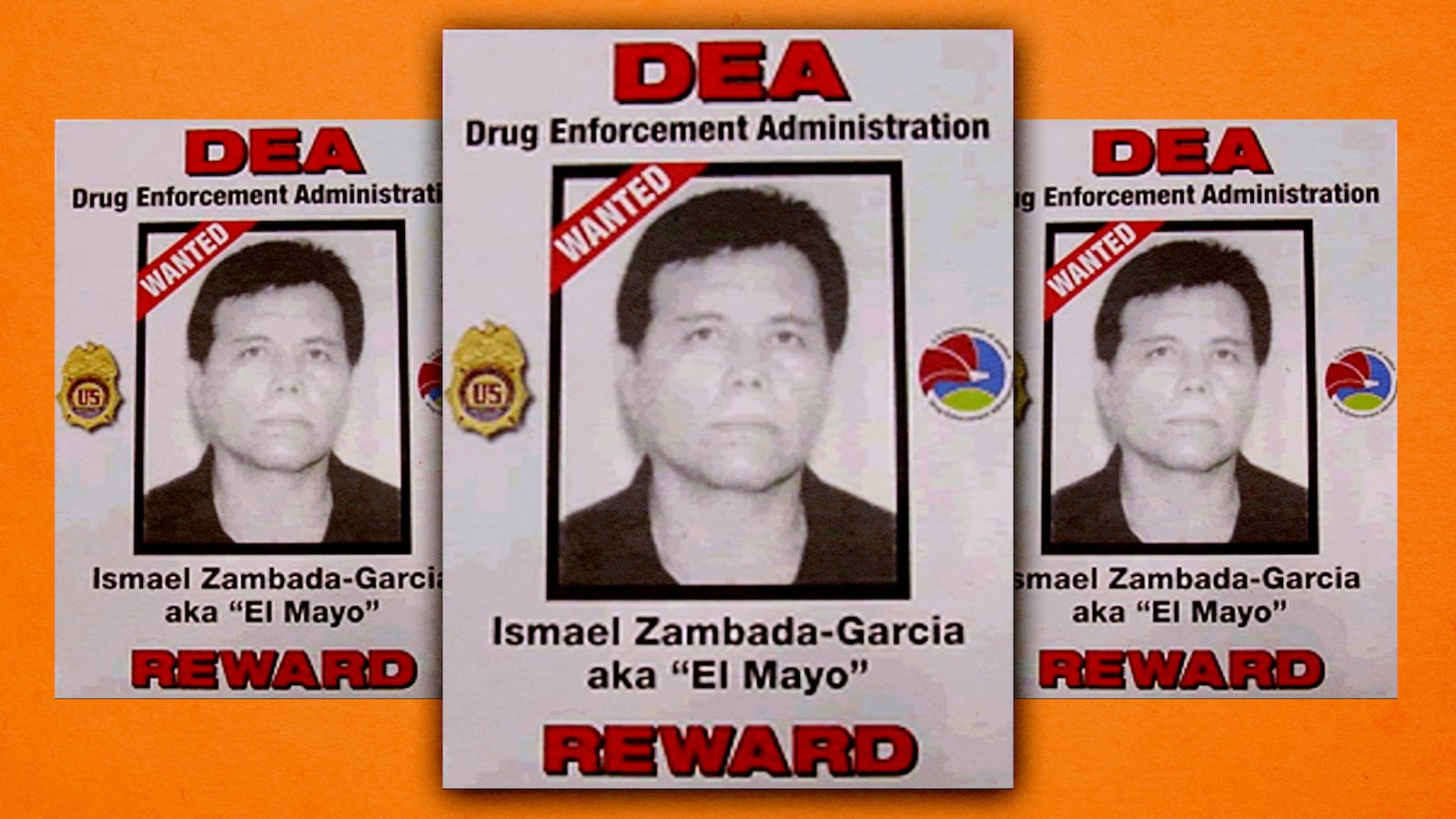

As El Chapo’s trial neared in New York, the Marines back in Mexico pressed on against the cartels, with his old partner, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, as a prime target. Two more Marines were killed when they were off-duty and just walking around the resort town of Cozumel in September.

The El Chapo trial commenced in November, with testimony detailing millions in bribes paid at seemingly all levels of government as well as every branch of law enforcement and the military save for the Marines. A firefight claimed the life of yet another Marine in December, as Mexico was concluding a year in which murders had risen by a third, from 25,036 in 2017 to 33,341 in 2018.

At the end of January, an already harrowing existence took what must have been a wrenching turn for the Marines. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador summarily called off the decades-long war on drugs in what appeared to be a desperate move aimed at reducing the body count by reducing turmoil in the cartels.

“There is officially no more war,” he declared. “We want peace, and we are going to achieve peace.”

He announced that the military would no longer seek to arrest cartel kingpins.

“No capos have been arrested, because that is not our main purpose,” he continued. “The main purpose of the government is to guarantee public safety.”

He added “What we want is security, to reduce the daily number of homicides.”

American law enforcement officials said that an extradition treaty with Mexico remains in effect, and the capture of El Mayo is still a top priority.

“Maybe it’s not a focus of theirs,” one federal agent said. “It is a focus of ours.”

An American official who has worked with the Mexican Marines felt sure they remained determined to capture El Mayo. He said that the spirit and courage of the Marines is on full display in a video that was taken of them advancing into mortal danger to capture El Chapo.

“Hurry! Hurry!” the marines can be heard shouting in Spanish midst gunfire. “Up the stairs!”

The official noted that the Marines fight on, day after day after day at great risk for scant personal gain.

“They get paid peanuts,” the official observed.

Meanwhile, the cartels continued to smuggle drugs by the ton into the U.S., almost none of it over unsecured stretches of the border, virtually all of it either by sea or through tunnels or in vehicles across already highly secured entry points. The day after the Mexican president declared the end of his country’s war on drugs, the New York state special narcotics prosecutor announced the recovery of 70 pounds of heroin and fentanyl. Those arrested included a man who gave his home as “Sinaloa, Mexico,” El Chapo’s home province and the base for his cartel.

On Tuesday, a jury found El Chapo guilty of smuggling hundreds of tons of heroin and cocaine into America. He would likely still be at liberty in Mexico were it not for the Marines.

The question now is whether Marines will be allowed to go after El Mayo and other monsters such as caused a gallant soul visiting New York to ask if he could just walk the streets because he could not do that at home.