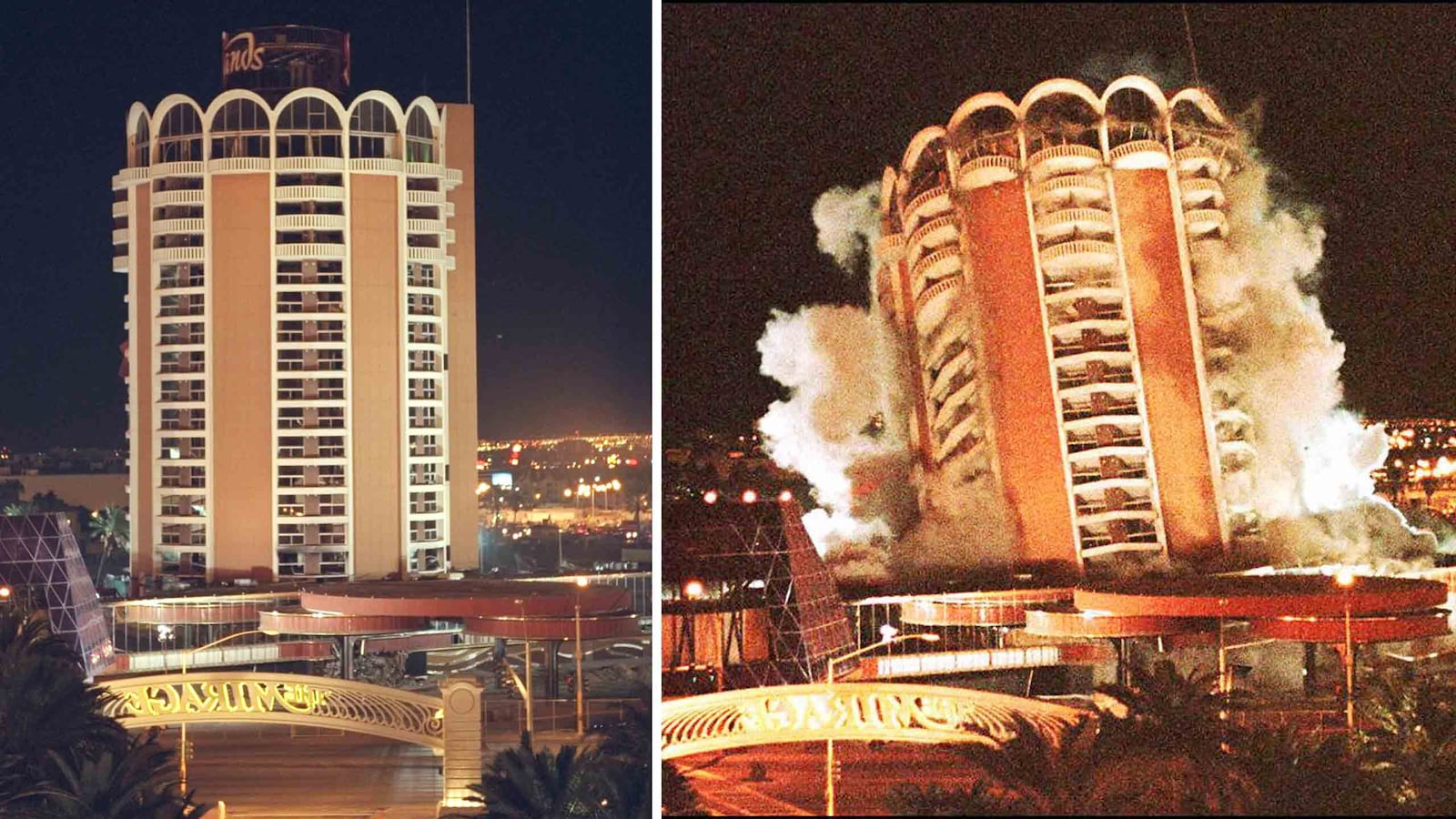

It was the last great show at the Sands Hotel and Casino. At 2:05 a.m. on Nov. 26, 1996, a gathered crowd cheered with an early morning raucousness known only to the not-so-sober as charges went off in rapid succession up and down the 17-story tower of the hotel.

Within seconds, the building had crumbled into a pile of dusty rubble.

For 44 years, the Sands had helped make Las Vegas the glittering, star-studded shrine to excess and revelry that it is notorious for today. It was the frequent haunt of the Rat Pack, of high-rollers with household names, and of Hollywood directors who came through with cameras rolling.

It changed hands between alleged mobsters and Howard Hughes and Sheldon Adelson before finally falling victim to its success. The hotel that ushered Las Vegas into its brilliantly lit future was no longer the star of the Strip, and it was spectacularly destroyed to make way for bigger and better.

Glamour, Celebrity, and Vice

Following the end of World War II, a building boom came to the sleepy desert town of Las Vegas. The city had one main thing going for it: Nevada was the only state where gambling in a casino was legal.

First came the “elaborate motor hotels with lavish casinos and theatre-restaurants attached—in rustic Western decor,” starting in the 1940s, as a New York Times article from 1957 reported. But in the 1950s, those rustically themed lodges gave way to more luxurious and modern hotel-casinos.

The Sands was among the first handful of hotels to be built in this new style along a stretch of land that would come to be known only by its shape—the Strip.

Naturally in those early days of Las Vegas, the initial ownership of the hotel is shrouded in rumors of mob ties and dirty money. But after the hotel ownership was put in the hands of Texas oilman Jake Freedman, the gaming commission allowed it to open on Dec. 15, 1952.

The original hotel was a fairly modest affair—by today’s Vegas standards, at least. The 212 guest rooms were situated in four buildings around a giant blue pool.

The compound contained a thriving casino, white-gloved restaurants, and spaces dedicated to entertainment, the most prestigious of which was the Copa Room officially opened with a run by singer Danny Thomas.

The hotel was advertised by a giant pink neon-lit sign (setting the look that would forever characterize the Vegas Strip) proclaiming “Sands: A Place in the Sun.”

By the late ’50s, the Vegas Strip may have been just a glimmer of the sanctuary to vice that it is today, but compared to the original town, things were changing fast.

In a 1957 article in The New York Times, writer Gladwin Hill noted that the boom was slowing down a bit, “Yet the flamboyant, neon-lit gambling and fun-in-the-sun center is doing a flourishing even expanding, business. For every one of its 50,000 inhabitants, 160 tourists are said to have visited Las Vegas last year, spending over $160,000,000.”

The very next year, another article implored readers to see beyond the bright lights. “Blinded by the casinos’ neon gutter, many a tourist fails to see the important industrial, scientific and other aspects of the Nevada resort.” But it was too late. The fate of Las Vegas had already been set.

The Sands wasn’t the largest hotel on the Strip, but it did become one of the most well-known thanks in large part to publicist Al Freeman.

Freeman knew that he had to make a name for the hotel—and the up-and-coming town—in order to lure in visitors.

He cozied up to movie and television producers, offering the Sands and Las Vegas as the perfect backdrop—or perhaps even a starring character (we’re looking at you, 1960-made Ocean’s 11)—for their productions.

He convinced actress Rita Hayworth to marry her fourth husband, Dick Haymes, in the hotel complete with a camera-ready guest list. He staged stunts like a now-iconic photo in which a craps table was dropped into the hotel pool—Sands sign visible in the background—and surrounded by bathing suit-clad gamers who rolled the dice while half submerged in the cool waters.

But the best press of all came after the Rat Pack made the Sands their home base. In October 1953, a 37-year-old Frank Sinatra began singing in the Copa Room at the Sands. With his rising popularity and dashing sense of style, Sinatra brought an explosive dose of glamour, celebrity, and vice to the formerly dusty Strip. By the early 1960s, his fellow Rat Packers (Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop) had joined him and the Sands had become the place to be.

The list of celebrities who made appearances around the casinos or on the stage over the years is a who’s who of Hollywood at that time: Lauren Bacall, Cary Grant, Mia Farrow, James Stewart, Carol Burnett, Lucille Ball, a pre-presidential John F. Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich, and Rosemary Clooney were among the scores of big names who made the pilgrimage.

But Sinatra was the center of the storm… and sometimes he also created it. The singer was known to gallivant around the property with his own entourage.

In one example of his diva behavior, George Levin, the maître d’ of the Copa Room from 1979 until the hotel’s close in 1996, remembers witnessing what happened when Sinatra was served mushrooms in his chow mein in the Garden Room, a white-gloved restaurant specializing in Chinese cuisine.

“Everything was silver at that time, silver plates and silver toppings, coverings. Frank lifts the thing up and there are the mushrooms… He took the bowl and threw it over his head. I stepped on the side and I started to laugh,” Levin remembered. “Frank gets up and he starts coming after me and I run into the kitchen. He comes after me into the kitchen and he says to me, ‘You want to fight?’ I said, ‘I’m not a fighter; I’m a lover.’ And he broke up, he hugged me and that was it.”

Sinatra may have been ready to fight anyone who crossed him, but he also fought for those who were being wronged. Beyond putting Las Vegas on the map, the singer played a large role in integrating the city.

One story goes that after he noticed his fellow performer Nat King Cole eating dinner in his dressing room, Sinatra invited the singer to join him in the main dining room, where black people were not allowed to eat at the time. He “told the hotel management that if African-Americans were not allowed in the dining room, he would have the entire wait staff fired.”

In another, Sinatra threatened to end the Rat Pack’s wildly popular “Summit at the Sands” show if group member and friend Sammy Davis Jr. wasn’t allowed to live at the hotel with the others. Hotel management gave in to Sinatra’s demand and Davis Jr. was given a suite, helping to pave the way for equal treatment of black entertainers in the city.

But like all epic nights in Vegas, the Sands meteoric rise in the ’50s and ’60s presaged the beginning of a long, painful end. In 1967, Howard Hughes went on a buying spree in Vegas; among his new acquisitions, he snapped up the Sands for $14.6 million. The movie mogul had dreams to expand the property—he oversaw the addition of a new tower with 777 rooms—but his reign also led to the devastating loss of its star entertainer.

On Sept. 11, 1967, Frank Sinatra announced that he was leaving the Sands for Caesars Palace. The lead in The New York Times piece covering the exit read, “Frank Sinatra walked out on his contract with the Sands Hotel here last night because the management ‘cut off his credit,’ a spokesman for the singer said today.”

Apparently, the lax—if not blind—eye the previous management had been taking toward Sinatra’s debt at the casino was not shared by the new powers in charge.

As they cut off his credit, their star threw an epic tantrum. According to witnesses, Sinatra climbed onto one of the tables and began screaming. He then threw a chair at the casino boss, who responded by punching him in the face, and left the hotel—by driving a golf cart through a window. The next day, he decamped to the rival hotel.

Without the luster of Sinatra, the Sands heyday started to come to an end. In 1988 Hughes sold the property. It went through several ownership changes before finally being acquired by Sheldon Adelson. In 1996, Adelson decided that the hotel had run its course. It was time to blow up the Sands and make way for the newest jewel on the Strip: the Venetian, a 7,000-room mega resort-cum-casino.

Las Vegas may still be a popular spot for gambling and partying the night away, but the glamour and magic of the era of Sinatra has largely come to an end.

“I wouldn’t give you two cents for Vegas today,” Levin told an interviewer at the Southern Nevada Jewish Heritage Project. “If I came into Vegas today, I think I would leave the next day… It’s not Vegas anymore. I don’t know what it is.”