Author’s note:

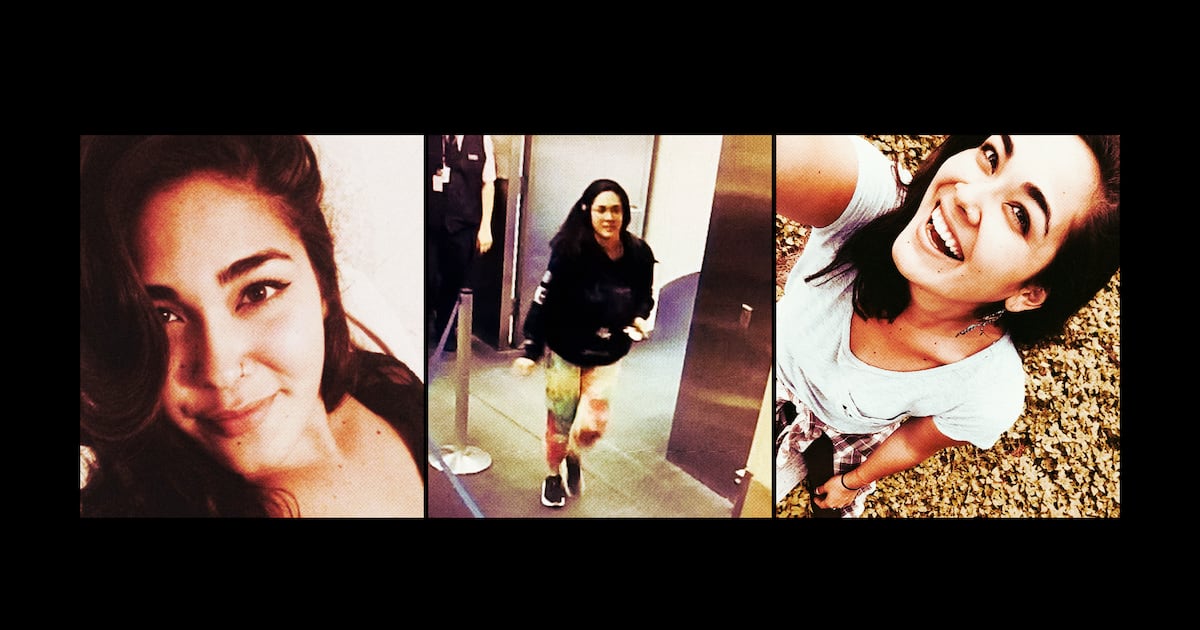

When I first set out to write The Elissas—the story of my childhood best friend Elissa’s time in the Troubled Teen Industry where she met two other young women, uncannily named Alyssa and Alissa, none of whom lived past 26—my main focus was on these three girls’ stories. I was eager to uncover what had happened in their adolescence that had led them to therapeutic boarding school, as well as what had occurred while they were in the industry’s care that had propelled them each to meet the same tragic fate. But in my research, a new nagging question began to present itself: what was it about the Troubled Teen Industry that so appealed to their parents?

What I discovered, and the passage below will illustrate, is that the purveyors of the Troubled Teen Industry are often master manipulators who prey on parents’ fears, vulnerability, and utter desperation to do right by their children—no matter the measure, or the price tag.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Jesus,” Claire said as she entered the station to get her daughter.

The cops apprehended Alissa in the cornfield, bringing her down to the precinct. This wasn’t the first time Claire had been down this road with one of her kids. Her older son, Matt, was frequently in trouble with the law. But his indiscretions far exceeded the limits of bad teenage behavior.

“Swatting” first made headlines in 2008, when people on the dark web began calling the police with fictional emergencies. Bomb threats, hostage situations, murder. While this may sound like a heightened form of prank phone calling, it’s a much more acute form of harassment. These calls trigger a SWAT team to descend on whatever address is shared, often the home of one of the caller’s enemies. People have died and others have been seriously injured as a result, leading legislators to push to classify the act as terrorism. And this was the world Matt had become enmeshed in—resulting in a litany of investigations, charges, and later on, arrests. When Claire walked into the station, she kept thinking about not being ready to go through something like this again.

“Mom, I’m—” Alissa said.

“Save it,” Claire said.

“You don’t understand, I was just getting snacks and—”

“Trust me, I understand.”

Claire was enraged, but taking in the totality of the situation, her anger turned to anguish. Realizing that the problem wasn’t Alissa’s actions themselves, but the root of them. That she was so desperate for alcohol that she was willing to steal it, so eager to party that she would do whatever it took. It wasn’t about what Alissa had done, but why she did it.

“Seriously, Mom.”

“Let’s just talk about this at home.”

“Fine.”

“Good.”

After the arrest, Alissa was forced to appear in court, and later pay a fine. A meager punishment, but one that went on her permanent record. Creating physical, concrete proof that she was trouble. And soon after, Claire started to look for help.

This is how the Troubled Teen Industry typically recruits families. A harmless, cursory Google search will spin into inquiries on a website for various facets of the industry. An educational consultant, who masquerades as a college counselor type, is often essential to the equation. They guide parents—like Alyssa’s and Elissa’s, who both employed them—through finding the best wilderness program, then therapeutic boarding school, for their child. What parents often don’t realize is that the consultants are often receiving financial kickbacks from these programs, earning a fee each time they place someone in their care.

Swing set

Samantha LeachClaire didn’t employ a consultant, having found Ponca Pines on her own. And for the first time in a long time, Claire felt hopeful. Yet there was still an obstacle in her way: John. Claire had married John when she was just 19 years old. They grew up together: becoming parents, then homeowners, maturing during their partnership. Even though he’d broken her heart, she still needed his buy‑in as a coparent. All matters pertaining to Alissa were difficult for them to discuss. John was upset that Alissa refused to visit him. The idea of boarding school didn’t sit well with him, either.

“What is boarding school going to solve?” John asked.

“John, you’re not with her every day. You’re not seeing it,” Claire said.

“Because she won’t come here. It’s not like I don’t want to see her.”

“I know, I know. That’s not what I’m trying to say. I’m just really worried.”

The Troubled Teen Industry plays on parents’ vulnerability. Claire was at the end of her rope: so worried about Alissa’s future and well‑being that she was desperate for some relief, any solution. According to many parents who have sent their teens to these programs, the educational consultants and program directors appear hyperaware of their concerns. The Alliance for the Safe, Therapeutic and Appropriate Use of Residential Treatment (A START) reported that recruiters typically stick to a script similar to this: “You’ve called just in time. We’ve seen this before. You need to enroll your child without delay. If you don’t, your child is on a path to jail, a mental hospital, the gutter, or the morgue. It sounds like you’ve lost control as a parent, and the only way to get control back is to let us impose discipline in a controlled environment. Let me take your application—right now. Remember, your child is in danger and there is no time to lose.”

“I’m sending her no matter what.”

“We’ll see about that.”

Claire’s desperation to send Alissa to Ponca Pines now makes sense to me. Why she and so many other parents would find it nearly impossible not to succumb to what these programs offer. I believe it’s because of the industry’s assurance that they’ll save their children from harm as well as rehabilitate them without any greater, societal consequences. Because they’re boarding schools, not actual rehabs. And as such, a child’s attendance is only a slight deviation from their preordained path, not a true pivot. These schools appear to offer a safety net, keeping upper‑class teens on the right trajectory to college, careers, prosperity.

Ponca Pines Academy Residence

Samantha LeachThat promise was all Claire knew of the Troubled Teen Industry; the press surrounding it was primarily positive. Though some exposés were written—including Maia Szalavitz’s seminal 2006 exploration of the industry, Help at Any Cost: How the Troubled-Teen Industry Cons Parents and Hurts Kids—the reigning narrative was that these institutions that practiced “tough love” were still the most viable solution for curbing a teen’s behavior. With articles detailing how Roseanne Barr, Barbara Walters, Kathy Hilton, and Farrah Fawcett had sent their kids to similar programs. Or that Nancy Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Princess Diana had all visited Straight, Incorporated: a chain of teen residential rehabilitation centers.

It wasn’t until 2020—when Paris Hilton released her documentary, This Is Paris—that the floodgates opened for conversations surrounding the dangers of the Troubled Teen Industry to hit the mainstream.

By 2020, my fascination with Paris had waned, yet I still found myself floored and stunned as Paris revealed that she’d attended Provo Canyon School, a therapeutic boarding school that’s still open to this day in Utah, where she alleges that she was restrained, involuntarily medicated, and placed in solitary confinement. Later she’d state that she was sexually assaulted by a non‑medically‑certified staff member, who digitally penetrated her while claiming to be performing a cervical exam late one evening. Taking in the news, I was overcome by a familiar yet unnerving sensation. A desire to call Elissa. To let her know that Paris had also been sent away. That our idol had shared this experience as well.

In the weeks that followed the film’s release, an entire generation of former Troubled Teen Industry students began coming forward on TikTok. They shared their own stories of abuse, neglect, and trauma. The hashtag #TroubledTeenIndustry has since garnered over 337 million views. But, as I’d later learn, these conversations weren’t just happening on TikTok. I also found that some of Elissa’s former classmates had started to identify as survivors rather than graduates. They maintained this heightened sense of urgency when we eventually spoke—wanting the truth of their experience to be known, too.

Excerpted from the book THE ELISSAS: Three Girls, One Fate, and the Deadly Secrets of Suburbia by Samantha Leach. Copyright © 2023 by Samantha Leach. Reprinted with permission of Legacy Lit. All rights reserved.