The targeted killing this past Friday of Major General Qassem Soleimani by a U.S. drone strike has greatly heightened fears over the outbreak of a shooting war between the United States and Iran that could further destabilize the entire Middle East.

Long recognized by experts of all ideological stripes as the master architect of Iran’s strategy of regional dominance in the Middle East, Soleimani, 62, was the charismatic commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force, which trains, funds, and directs pro-Iranian militias throughout the Middle East and Africa.

Trump administration spokespersons have described the strike as a pre-emptive one. They claim that Gen. Soleimani had been planning imminent strikes against American diplomats and military installations in the region.

The general was a national hero in Iran. He is widely recognized as one of the most influential figures in Middle East geopolitics over the last decade or more. Few experts would quarrel with the assertion that Gen. Soleimani has been an exceptionally effective politico-military operator, who has repeatedly frustrated American policy in the region since the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003.

How might Iran respond to Soleimani’s killing? Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, promised “forceful revenge.” Yet if history is any guide, Iran’s response is likely to be subtle and carefully calibrated to avoid a major conflagration with the United States.

The United States, Iran, and their allies in the region have been locked in what historian David Crist calls a “twilight war” for more than forty years now. Insights into how this chapter of that conflict may play out can be gleaned from the long and complex history of that conflict. The Iranians have long proven themselves to be highly skilled practitioners of irregular warfare, i.e., conflict in which politics and unconventional military action figure much more prominently than in conventional military conflicts.

So how and when did the twilight war start?

In February 1979, a bizarre coalition of liberals, leftists, and fundamentalist Muslim clerics overthrew Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. It was without a doubt one of the most improbable and unanticipated events in modern history.

With the help of American largesse and spiking oil revenues, the Shah had transformed his country from a traditional Shia Muslim society into a modern, secular one over the course of a mere quarter-century. By the mid-’70s, the Shah commanded the largest army in the Middle East. Iran had become a great regional power. It was viewed in Washington as a bulwark against Soviet expansion in the oil-rich Persian Gulf, and, as President Jimmy Carter put it, “an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas” of the world.

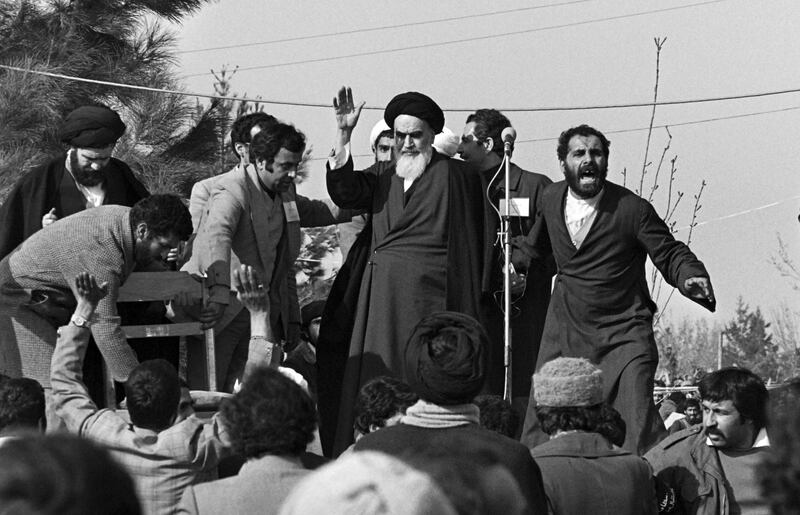

Led by a glum yet mysteriously charismatic cleric named Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the clerics rapidly outmaneuvered and marginalized their revolutionary allies, and established an Islamic Republic. Khomeini hoped to export his creed of “Death to America” and political rule via Islamic law to the Muslim masses elsewhere, and he enjoyed immediate success in doing just that.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini waves to a crowd of supporters gathered at the Behechte Zahra Cemetery in Tehran during his visit on the day of his return from France after 15 years of exile, as the insurrection against the Shah's regime spreads all over the country.

Gabriel Duval/GettySoon after the Ayatollah established the Republic, the United States severed diplomatic relations with Iran. It’s been called the geopolitical divorce from hell, and not without good reason. The twilight war has been waged largely through a bewildering variety of political, economic, and diplomatic means, but also through violent struggle via proxy forces, special forces operations, and occasional conventional combat, mostly naval in nature.

Resentment against the United States runs very deep in Iranian political circles today. It has its origins in the Cold War. In 1953, the CIA staged a successful coup against an eccentric Iranian prime minister named Mohammad Mosaddegh, on the grounds that he was growing too friendly with the Soviet Union and threatening to nationalize the British-run petroleum industry.

The Americans reinstated the Shah, who had been recently been deposed by Mosaddegh. With American money and support, the Shah over the next 25 years brought Iran into the modern world. Annual economic growth rates in the ’60s and ’70s averaged about 9 percent of GNP, a heady clip, but most of the country’s newfound wealth and power went to close associates of the Shah’s family and a burgeoning upper class. “The byproducts of his brand of modernization,” writes Crist, “were rapid social change and increased instability,” as inflation, corruption, and rapid urbanization created powerful resentments against the regime among the clerics, political intelligentsia, and the rural masses.

Growing social problems, coupled with intensifying political repression and a consensus within Iran’s political intelligentsia that the Shah was in Washington’s pocket, undermined his legitimacy and led to mass protests and chaos. The Shah’s indecisiveness and Washington’s obtuseness during the initial stage of the Revolution—the Americans had no contacts at all with the growing opposition movement—greatly exacerbated problems.

On Nov. 4, 1979, student radicals seized the American embassy in Tehran—they called the compound “the den of spies”—taking 66 Americans hostage, and creating a world-wide media sensation. Carter pursued a variety of strategies to free the hostages, including a badly bungled rescue effort that left eight American servicemen dead in the Iranian desert.

Muslim fundamentalists the world over could hardly hide their glee. The hostages weren’t freed for 444 days—until Ronald Reagan had become president. “Coming on top of America’s failure in Vietnam and a steadily worsening economy,” opines historian George Herring, “the hostage crisis came to symbolize a rising sense of impotence and belief that the nation had lost its moorings.”

Iran, once the strategic linchpin of American policy in the Middle East, was transformed into the epicenter of Muslim resentment against Western imperialism and the “Great Satan,” as Khomeini called the United States. The loss of Iran as a strategic partner, coupled with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, prompted Carter to announce in his 1980 State of the Union address that the United States would use military force to defend its interests and allies in the Middle East. This marked the beginning of the American military’s shift in orientation from the plains of Europe to the sands of the Middle East.

Ever since the hostage crisis and the enunciation of the “Carter Doctrine,” Iran and America have pursued directly conflicting objectives and strategies in the Middle East, narrowly evading full-blown war on several occasions.

In 1983, Iranian-trained and -supported Hezbollah fighters blew up the Marine barracks in Beirut, killing 241 Marines. President Reagan opted to withdraw U.S. peacekeeping forces from the Lebanese Civil War rather than escalate the conflict there, or attack Iran. His failure to strike back emboldened Iran to expand its support for anti-Western forces and projects in the region.

Nonetheless, Reagan went on to write three letters to Khomeini in the following years urging a rapprochement. All three were met with stony silence.

The United States provided intelligence and support for Saddam Hussein’s Iraq toward the end of its eight-year war with Iran (1980-88). Hundreds of thousands of people in both nations were killed. Near the end of the conflict, Iran tried to prevent the free flow of oil by mining the waters in and around the Persian Gulf. When an American frigate was damaged by an Iranian mine, the U.S. Navy struck back hard in Operation Praying Mantis on April 18, 1988. By the end of the one-day operation, American Marines, ships, and aircraft had destroyed Iranian naval and intelligence facilities on two oil platforms in the Persian Gulf and sunk about half the ships in the Iranian navy.

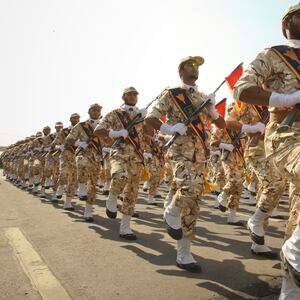

Revolutionary Guards in green uniforms march over a U.S. flag spread on the tarmac in Azadi square, Tehran, whilst carrying banners with photos of Ayatollah Khomeini on the third anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, Feb. 11, 1982.

Kaveh Kazemi/GettyIn the ’90s, Bill Clinton’s administration remained deeply concerned about Iran’s support for Muslim extremism and terrorism, but nonetheless made several overtures to Tehran to de-escalate tensions. These efforts came to nothing, in large measure because anti-Americanism had become an indispensable pillar of the Islamic Republic’s ideology.

In 2000, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright apologized for America’s role in the 1953 coup, but because Albright criticized Iran’s domestic and foreign policies at the same time, Tehran rebuffed her apology.

Meanwhile, Iran’s Revolutionary Guard special forces, the Quds Force, had been energetically expanding its network of politico-military partners, allies and proxy forces throughout the Greater Middle East to enhance Iranian influence throughout the region. Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Palestinian territories, Israel’s most ardent enemies, were but two of the better known organizations to enjoy financial support and training from the Quds Force. There were many, many others.

In 2002, the world learned for the first time of Iran’s nuclear development program. For the next decade the U.N., the E.U., and especially the United States imposed a welter of economic sanctions on Iran and her trading partners, but the nuclear program proceeded apace until Iran signed the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPA) with six nations, agreeing to stringent limitations on the program in exchange for the lifting of sanctions.

Over the last dozen or so years, Iran has funded innumerable strikes by proxy forces against American forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. And the Quds force has planned a lot of military operations of one sort or another against American units as well as those of America’s allies.

In 2011, a Quds Force officer organized an assassination attempt on the Saudi ambassador to the United States, to take place at a swanky Georgetown restaurant. American security agencies uncovered the plot.

This sort of politico-military activity led CENTCOM commander General James Mattis to remark in 2012 that he had three countries constantly on his mind: “Iran, Iran, and Iran.”

According to Rand Corporation analyst Ariane M. Tabatabai, Iran’s foreign policy over the past few years seeks “to balance two oft-conflicting objectives: undermining [neighboring] central governments to ensure none would become strong enough to pose a threat to Iran, while also striving to prevent them from collapsing.” Now, Iran aggressively supports Shiite militias in Iraq that are hostile to the U.S.; Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the Houthis in Yemen in their war against U.S. ally Saudi Arabia.

Iran currently has ties to organizations that together make up about 200,000 hardcore anti-Western fighters. Brian Katz of the Center for Strategic and International Studies writes that “these groups view Tehran and each other as battlefield partners, ideological allies, and separate flanks in a common regional front.”

Vali Nasr, the Iranian-born former dean of the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins, claims that Tehran’s relative power and influence throughout the region has grown substantially in the last few years, especially in Iraq and Syria.

The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” strategy is designed to rein in the activity of this vast network, as well as to secure a new agreement about the nuclear development program that places even tighter strictures on its activities than the current deal.

Critics of the Trump policy, of whom there are a great many, question whether dramatic military strikes, such as the targeted killing of Gen. Suliemani, are likely to forward those ends.

Peaceful resolution of the current crisis depends in large degree on both sides’ ability to transcend the tortuous history of the last four decades, to jettison the self-defeating attitudes and ideas that shaped it, and to establish new protocols and ground rules to manage their conflicting strategies and goals in the region.

Bringing this latest chapter in the twilight war to a non-violent conclusion is clearly going to be very difficult, but it’s not impossible. The two adversaries have sharply conflicting geopolitical visions of the region; both sides see themselves as pivotal players in shaping the politics of the Greater Middle East. Each side sees the other as playing the game via illegitimate and illegal means.

The twilight war between Iran and the United States isn’t going to disappear into thin air anytime soon, but it could clearly be better managed through negotiation and compromise rather than military operations. Both sides must find the discipline and imagination to put aside the bitterness and recriminations that have poisoned relations for the last 40 years, and begin to talk in more measured, concrete terms about what can be done to diminish and control the acute tension that now threatens to spill over into a shooting war neither side wants.