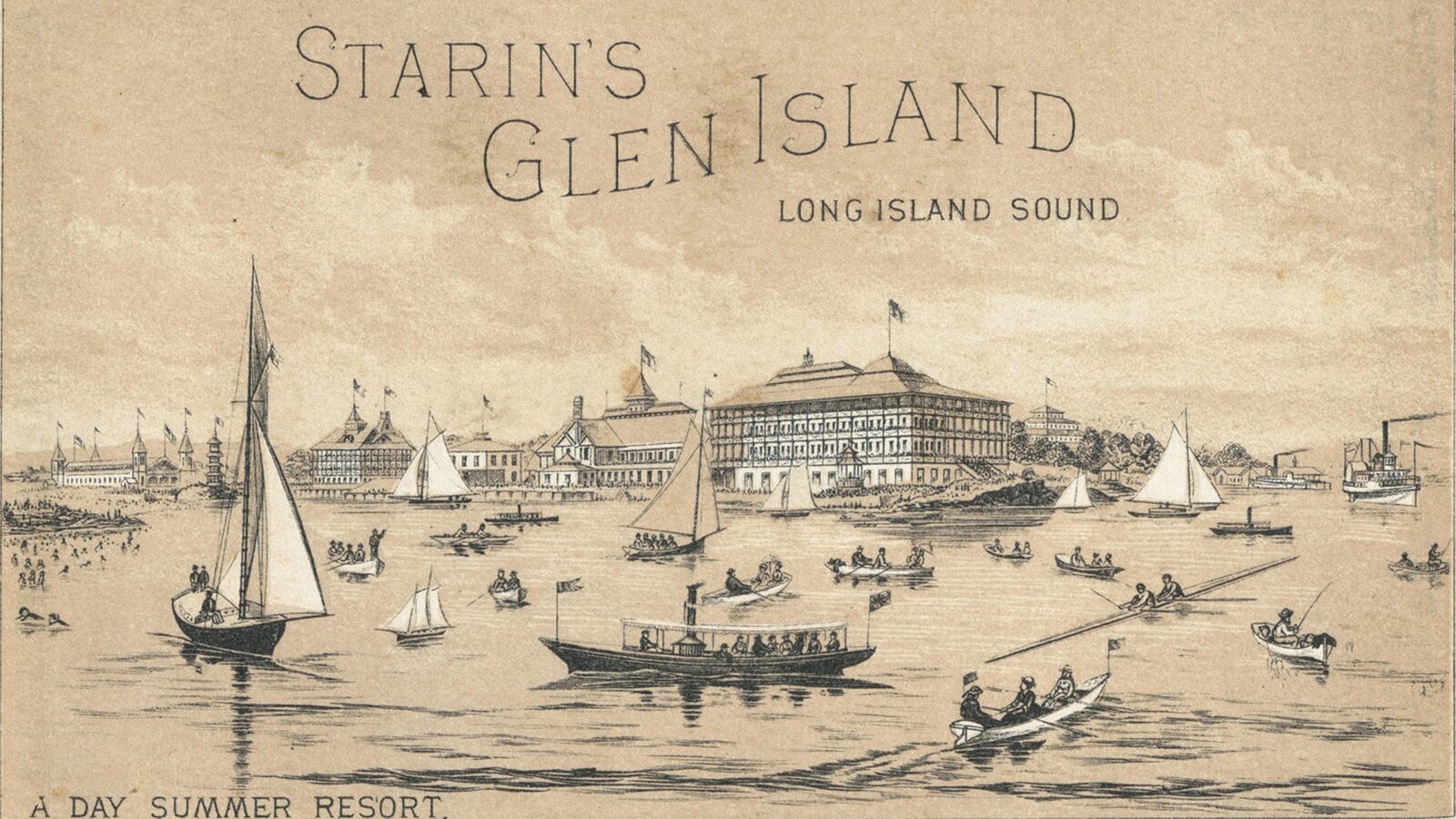

Imagine it’s Memorial Day in 1900, and you are desperate to escape the bustle of New York City. Luckily for you, you can board the steamboat for a day-trip to the Disneyland of your era: Starin’s Glen Island.

This turn-of-the-century amusement park may not be a household name today, but at the end of the 1800s, it was one of the biggest and most successful such enterprises in the country.

For over 25 years from 1879, millions of people traveled to the series of islands off the coast of New Rochelle that former congressman John H. Starin had transformed into the “World’s Pleasure Grounds.”

But after a steamboat accident in 1904 slowed the tide of tourism and Starin’s death in 1909 left a vacuum in leadership, the amusement park fell into difficulties. The attractions were shuttered, some of the buildings burned to the ground, and Glen Island was auctioned off for a pittance. Today, all that is left of the once thriving carnival of fun are a few ruins.

Starin was a wealthy and influential man by the time he began his search in the mid-1870s for the perfect land on which to build the attraction of his dreams.

He had made his fortune in the transportation business—mostly of the water variety, which would come in handy for his new venture—and he had served for four years in the United States Congress. (After founding Glen Island, he would go on to become the president of a bank and continue building his fortune in the river and railroad transportation businesses.)

But after a two-year search, he finally found a “suitable locality” in what was then-known as Locust Island, which had been serving as the summer home for a “gentleman of means.”

An 1879 report of the purchase in the New York Times describes the island in glowing, if improbable, terms: “A breeze from any quarter cannot ruffle the blue waters surrounding the island without sweeping over it also, and under its shade trees oppressive heat is almost unknown.”

From the outset, Starin made his intentions clear—he wanted to turn his island into “the most popular picnic resort in the country.” But don’t even think about mistaking his proposed theme park for any ordinary den of summer vice. He also wanted it to be known as “the most orderly one and to banish from it all disturbing elements that are so frequently found at similar places.”

Starin was a bit of a teetotaler—no alcoholic beverages were to be transported to the island. It was a decree he could confidently uphold given that all guests would make the hour-and-a-half trip to the island on boats he owned. It was also one he would eventually overlook at least in one area of the park. When Little Germany was created, a German beer garden was prominently installed.

But those pleasures would come later. At first, this island of amusements was a lot simpler in its conception. There were areas for picnics and paths for walking; there were grottos for swimming, with the attendant beaches and bath houses, and horses for riding. There were musical acts and dance floors, restaurants and clam bakes.

But from these simple pleasures, things rapidly expanded. In less than a decade Starin’s Glen Island had grown to occupy seven small islands connected by pedestrian bridges. A plaque that can still be found in the area describes the layout of the amusement park.

On the main island—Glen Island—you would find all of your carnival-worthy attractions: billiards, bowling, carousel rides, and a rifle range; for more vigorous pursuits there were donkey and pony rides, swimming areas, walking paths, and dancing pavilions; there were also manicured gardens and a large aviary.

Clubhouse Island was where the popular “Rhode Island Clam Bake” was held, where each family could enjoy an all-inclusive feast for a whopping 75 cents a person.

Beachlawn was all about the swimming holes and beaches, as well as being the location of the Chinese Pagoda, whose bell would ring out to welcome each new batch of guests to the park’s docks.

The award for “most sporty” went to Islandwild, where baseball, croquet, and biking could be enjoyed, while Glenwood featured an impressive zoo that boasted “the largest herd of buffalo outside of Yellowstone National Park.”

Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany, featured a castle and beer garden modeled after its country of inspiration. (You could also fish and boat from its shores.) The final island, New Venice Isle, was added in 1897, and wooed visitors with its natural history museum and sea lion pond.

“To speak of the inviting resort in Long Island Sound which is visited daily by so many thousands of pleasure seekers simply as Glen Island is inadequate,” an 1897 New York Times piece reads. “A few years ago it was a bunch of rocks barely jutting out of the water. When completed it will be a fantastic fairyland three acres in dimension.”

Needless to say, the park was a rousing success beloved by families near and far. It probably didn’t hurt that Starin, who no doubt made a more-than-decent profit by owning the steamboats that transported patrons to the islands, didn’t charge an entry fee to the resort.

From May to September every year, while Glen Island’s official “season” was in full swing, the pages of the New York Times would be dotted with its goings-on. The newspaper of record notes the throngs of visitors that show up in increasing numbers, the addition of attractions like a deer park in 1889, and special programming put on by such upstanding groups as the Women of the National Life-Saving Society.

In 1887, a rumor began that Starin might sell the resort, but he reportedly turned down even the hefty sum of $1.7 million. (“Glen Island is one of Mr. Starin’s pet hobbies and it is doubtful if any amount of money could induce him to part with it,” the New York Times report concludes.)

In 1894, there were so many visitors from Harlem that Starin added a twice-daily direct boat service, in addition to the regular departures from Lower Manhattan.

As each new season opened, gossip abounded as to the cultural theme of the year, many of which do not hold up in moral hindsight. (In 1901, an entire Sioux Tribe took up residence on the island as the latest “exhibition.”) For Fourth of July celebrations, there were 38-gun salutes at sunrise and sunset and additional bands booked to entertain the crowds.

But for all its popularity and novel innovations, when the end came for Starin’s Glen Island it was relatively swift. In 1904, a steamboat unconnected with the amusement park caught fire and 1,000 passengers died.

The accident led to a sharp decline in visitors for all area resorts accessible primarily by boat. Five years later, Starin, who had propped Glen Island up as his pet project, died.

Times were changing and the prospects for the resort didn’t seem quite so rosy. In 1915, Starin’s Glen Island hit the auction block. Two days after a disheartening performance that netted zero bids, the entire theme park was offloaded in a foreclosure sale for a mere $100,000 to the only person who made an offer.

Over the ensuing decades, bits and pieces of the island have changed hands. It has hosted a casino and an events venue, and large swaths have been turned into a public park.

But the attractions that once offered escape and entertainment to millions of New Yorkers are no more, and nearly all traces of the exotic sights and rousing amusements that once could be found on the “nest of islands” have disappeared.

“Today, it’s hard to believe that Glen Island ever was the resort Starin created,” wrote a Georgetown University history major after a visit in 2017. “The only remains of the park are Little Germany, where two castles and many stone structures still stand. Today, one castle was boarded up and the other, where the beer garden once sat, is used for Westchester County storage… Only two plaques on the entire island mention Starin.”