Part I: The Dream

In her dream, NYPD Chief Joanne Jaffe could hear the murdered girl calling to her for help.

“From the grave,” Jaffe would recall.

When Jaffe awoke, she figured she must have been dreaming of the teenager who had been raped and strangled just down the block from her childhood home in Queens.

Jaffe had only the haziest memory of the killing, but she did recall talk of one disturbing detail: a hairbrush up the girl’s vagina.

The dream haunted her, so Jaffe asked her mother and her sister whether they remembered the decades-old murder. Neither did. Jaffe phoned a friend who was a sex-crimes prosecutor at the Queens District Attorney’s office, suddenly doubting whether the girl had been real, or if the dream was just some craziness on her part. She guessed the slaying would have been around 1970, when she was 12.

Jaffe’s friend said she would check it out and soon reported back via email:

“Hi there… our homicide investigations chief is looking into this. Our own records do not start until 1973, so that doesn’t help, and there is no one in the homicide bureau who was here then and is still here now.”

The friend said she would also put in a call to Judge Greg Lasak, who had formerly been head of the Homicide Bureau at the Queens DA’s office. “[Lasak] has a memory like an elephant,” the friend added.

The friend soon emailed again.

“Joanne, I spoke with now Judge Lasak, who instantly remembered the case, although he wasn’t there at the time. He said that Det. Patty Kelly had the case. He is now 80. Greg will call him at home and find out more information. It was in the early ’70s. There was no arrest, he thinks. Sounds like a good case for DNA and the cold case squad…”

Jaffe emailed back asking for any details that Kelly could remember. She thanked her friend, and hoped it was the same girl.

“I am so excited because I didn’t know if I was dreaming this stuff,” Jaffe wrote.

“No, it doesn’t sound like you are dreaming,” the friend replied. “I think it is unlikely that there was more than one rape-homicide involving a hairbrush in the vagina in the early ’70s.”

Unfortunately, Detective Kelly could recall only the scantest details of the case. But Jaffe and her friend were able to determine that the body of a 17-year-old named Leslie Zaret had indeed been found in a schoolyard just a block from Jaffe’s childhood home in the summer of 1974.

And the killer had left a hairbrush in the girl’s body, just as in Jaffe’s dream.

What Jaffe had not remembered was that she’d only been a year younger than Zaret at the time of the murder. She’d often played on that schoolyard as a child. The killing had been so close to home in more than one sense. She must have blocked out any memory of it.

“I could have been her,” Jaffe later told The Daily Beast. “Anyone, anyone could have been her.”

Jaffe wondered aloud if the murder may have been part of the reason she—the daughter of a pharmacist and sister of a pediodontist—had become a cop.

“I guess subconsciously, I felt unprotected and I wanted to be protected and I didn’t want it to happen to anyone else,” she said.

NYPD Chief Joanne Jaffe

Slaven Vlasic/GettyJaffe had started out her career as a rookie in the roughest part of Brooklyn, at a time when the city was a war zone. She was one of the first cops at the scene of the Palm Sunday Massacre in 1984, where eight children and two women had been shot to death. A 13-month-old baby girl was found unharmed, and a photo of Jaffe holding her had appeared on the front page of the New York Post.

“THE ONLY SURVIVOR,” the headline read.

Jaffe subsequently adopted the girl and spent her career seeking to keep bad things from happening to good people. Along the way, she became the first female three-star chief in the history of the NYPD. She was now in a position to revive the hunt for a long-ago killer who had desecrated Leslie Zaret’s body. Maybe she could answer the murdered teenager’s cries from the grave.

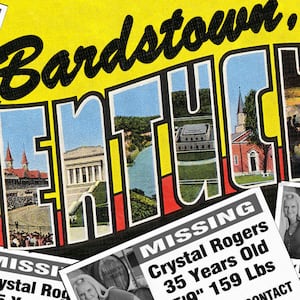

Part II: Who Killed Leslie Zaret?

Jaffe needed to review what had already been done in the case. She was told that the case records and vouchered evidence would be impossible to locate after so many years. But with the help of Chief Jack Travis, detectives soon found several boxes containing reports and notes on the Zaret homicide. They even found a particular item left at the scene of the crime.

“No one even thought we would find the hairbrush,” Jaffe said.

The commander of the Queens Cold Case Squad, Lt. Phil “Sundance” Panzarella, assigned Detective Mark Valencia to the revived investigation. Valencia was famous for his memory. “They used to joke and call me Rain Man,” he told The Daily Beast.

He was also relentless. “I never ever, ever quit,” he said. “Never.”

Jaffe was convinced that he was exactly the right detective to be working it. They conferred regularly as Valencia worked the case.

“He became as obsessed with the case as I was,” Jaffe said.

Valencia’s first step was to go to the 111th Precinct station house, which covers the Bayside neighborhood, where Zaret’s body was found.

He reviewed the case folder on Zaret’s open homicide, Valencia read the DD-5s, the forms known as “Fives” with which detectives are supposed to chronicle each step of an investigation. Detective Kelly’s “Fives” on Zaret were clear, concise and detailed.

Valencia read that Leslie Zaret had spent the evening of Friday, Aug. 16, 1974 with her best friend, 18-year-old Laura Gold. Leslie left Laura’s home on 58th Avenue around 11:30 p.m. She began to walk the 26 blocks to her home at 138-54 68th Drive.

Six blocks on, Leslie stopped into a bar on Main Street, where a boyfriend of hers worked. He was not there and Leslie proceeded on.

Her usual route would have taken her onto the overpass across the Long Island Expressway. She would have continued on down Main Street with the deep darkness of Mount Hebron Cemetery on her right.

On her left would have been John Bowne High School, where she had graduated two months before. Just beyond that was Queens College, where she was due to start in September.

At the corner beyond the cemetery, her expected route would have taken her to the right. Another block would have brought her to the garden apartment where she lived with her parents.

But she never arrived. Her father, David Zaret, called the police at 5:17 a.m. to report her missing.

At 8:20 a.m., a custodian found Leslie’s body six miles away, lying face up on the concrete schoolyard behind PS 203 on Springfield Blvd. She was completely naked save for a gold necklace, two gold earrings and two gold rings. Her only visible injuries were bruising and scratches on her throat. Her long-sleeved, blue, flower-print blouse, blue jeans and underthings had been folded and placed in a neat pile along with her beige platform shoes, just past her bare feet. Her legs were splayed. The handle of the hairbrush was visible where it had been inserted between them.

A man who was walking his dog happened past and the custodian, Saul Remph, called him over to watch the body while he went to get help. Remph subsequently told detectives that the gate to the fence surrounding the area was locked at off-hours. Only somebody familiar with the school or neighborhood would have known about the holes that vandals had cut into chain link at the far side of the yard, adjacent to a wooded patch that separates the school from Queensborough Community College beyond.

The Fives showed that the detectives had been unable to come up with a witness after canvassing every home in a five-block radius of the school. They had no more luck as they retraced what they figured was Leslie’s path on the way home.

An autopsy confirmed that she had been strangled. No attempt was made to collect DNA, as this was years before such forensics were possible.

The detectives had identified a number of possible suspects. They included a 21-year-old who was out on bail after being arrested for a sexual assault exactly two weeks before the killing.

Valencia noted that when the detectives spoke to the suspect in the immediate aftermath of Leslie’s murder, he had his bags packed and had bought a plane ticket to California, even though he had an upcoming court date, and failure to show would have meant the bail his parents posted was forfeit. The suspect was dissuaded from attempting the trip and subsequently pleaded guilty to the earlier sexual assault. He served 17 months in state prison.

But the detectives who had investigated that previous case seemed to have considered it an acquaintance or date rape and accorded it less gravity than they likely would have a stranger rape. Neither they nor the detectives investigating Leslie’s murder seemed to have obtained a full and detailed account from the first rape victim.

So, 30 years later, Valencia sought out the woman and spoke to her where she now lives, outside New York. During their conversation, she revealed something that shocked him—a detail that might have changed everything, had it been known back in 1974.

The woman told Valencia that she had encountered the suspect in Manhattan at Club 82. Once a mob-owned drag queen venue frequented by Hollywood stars ranging from Elizabeth Taylor to Judy Garland. It had since morphed into a rock music spot featuring artists like the New York Dolls and Debbie Harry.

By the woman’s account, the suspect bummed a ride with her when she left the club. She told Valencia that they stopped at the 24-hour Hilltop Diner in Queens. He asked her if she wanted to go buy some pot and maybe smoke a little.

She agreed and he directed her to Cunningham Park in Fresh Meadows. She was beginning to realize that the pot was just a ruse to get her to a dark and secluded spot when he knocked her down and pounced. He tore off her clothes and attempted to rape her, but was unable to achieve an erection.

At that moment, he suddenly turned her over face down. He grabbed her comb and inserted it into her rectum.

The suspect was fully aroused when he then rolled her over again. He proceeded to rape her while throttling her with both hands. She almost certainly would have been murdered, Valencia figures, had she not managed to knee him and break free. She escaped and reported the attack and went to a hospital, which confirmed there had been a rape.

The woman had been interviewed by detectives back then regarding both her case and the Zaret case, but she may have simply been too embarrassed to mention the comb. She was in tears as she now told Valencia that she was giving a full account of the attack for the first time.

On hearing of the comb, Valencia’s next thought was of the hairbrush.

Part III: ‘This was the 1970s’

Valencia theorized that the suspect may have been out driving that night when he saw Leslie making her way home on foot.

Had he been keeping to the script of the sexual attack the week before, the suspect might have asked Leslie if she wanted to go score some pot. She might well have agreed and joined him in his car.

“This was the 1970s,” Valencia noted.

If the suspect stuck to the script, maybe they would have driven to a dark and secluded spot. The suspect would have suddenly pounced and assaulted her with a hairbrush, just as he had used a comb.

But the first victim had been bigger and stronger than Leslie—more able to fight off her attacker and escape.

Leslie was only 5 feet, 1 inch tall, and weighed just 105 pounds.

Valencia believes that Leslie’s body was in the suspect’s car when he parked it in his family’s garage. Valencia further figures that the suspect borrowed his father’s car and drove to Club 82 in Manhattan, where he got in a tussle.

“To alibi himself,” Valencia theorizes.

The next likely step would have been to return home, switch cars again and drive Leslie’s body to the schoolyard.

As Valencia sees it, the killer staged the crime scene. The naked body. The neatly folded clothes. The splayed legs. The protruding hairbrush. All of it seeming to Valencia to be sending a message:

“Look what you made me do.”

Valencia was all the more certain he had identified the killer after he read a Five reporting an interview with the suspect’s then-girlfriend in the immediate aftermath of the killing. She had told detectives that the suspect came by her home late on the night of Leslie’s murder. She said he had smelled strongly of feces. Strangulation victims often lose control of their bowels.

Valencia tracked down the ex-girlfriend. She told him she knew why he had come, speaking the name of her former boyfriend.

“Because he killed that girl,” she said.

Valencia also interviewed five other young women who had encounters with the suspect. Their accounts formed a pattern leading up to the sexual assault for which he was convicted.

“It progressively got more violent up to the rape,” Valencia later said.

But even with the new details of the prior sex attack, and the stories of the other women, the Queens District Attorney’s office still felt there was not enough to prosecute. Valencia’s boss, Lt. Phil Panzarella, decided that Valencia had gone as far as he could. Panzarella directed Valencia to bring the suspect in with the hope of jarring him into incriminating himself.

The suspect was now living outside the city. Valencia and a partner pulled him over near his present home. Valencia recalls that the suspect agreed to join them in their car only to begin protesting as they started towards Queens.

“I can’t go to Queens, I got to pick up my daughter,” the suspect said, by Valencia’s account.

Valencia asked the suspect if he would go with them to a nearby police facility. The suspect agreed.

There, the detectives offered the suspect some water. He accepted and drank, but seemed to have surmised that the detectives were hoping to recover the cup and get a sample of his DNA. He may even have known the detectives could not take it as evidence until it had been discarded.

“He wouldn’t let the cup go,” Valencia later said. “He’s holding an empty cup.”

But as the questioning continued, the suspect seemed to forget himself. He suddenly jumped up from the table and slammed down the cup.

“I want to go home now!” he exclaimed.

Valencia’s partner positioned himself between the suspect and the cup.

“Okay, okay, I’ll walk you out,” Valencia quickly told the suspect.

They exited the station house.

“Come on, I’ll drive you home,” Valencia said.

“No, I’ll walk,” the suspect said.

Valencia pointed out that it was a particularly cold day.

“I’m going to walk,” the suspect said. “I need the air.”

Then, Valencia says, the suspect added, “Besides, I’m not getting back in your car because I know I’m never getting out.”

The man started off on foot. A local detective turned to Valencia and asked what he thought.

“You want my instinct?” Valencia asked. “If he looks back, he’s guilty.”

Valencia later reported to The Daily Beast, “He turned around four times.”

Part IV: From the Grave

Thanks to the cup, the detectives finally had a sample of the suspect’s DNA. But no genetic evidence had been collected in the original homicide investigation.

Meanwhile, the suspect contacted a prominent Queens criminal defense attorney. That meant the detectives could not speak to the suspect unless his lawyer was present. And the lawyer was surely not going to allow him to say anything incriminating.

Still, there remained a possibility that some trace of the killer could be recovered from Leslie’s body. She may have scratched her assailant and some of his DNA might be recovered from under her fingernails.

Valencia huddled with the sex crimes unit at the Queens District Attorney’s office and they decided to seek the permission of Leslie’s family to exhume her.

One complication was that the family was Jewish and religious.

“You try to convince a Jewish family to exhume someone who’s been buried for 32 years,” Valencia later said.

The father, Dave Zaret, had died in 1995. The mother, Charlotte Zaret, needed some persuading, but finally agreed to allow her daughter to be exhumed for one day after Valencia promised that everything would be left exactly as it had been.

“She told me, ‘You’re in charge of my baby,’” Valencia recalled.

Valencia drove the mother and her brother to Wellwood Cemetery in Suffolk County, so she could see exactly how everything was before the grave was disturbed. Valencia had been there on a number of occasions, including on the anniversary of the murder in the hope somebody might show up. He offered the mother a small warning as they approached.

“Watch your step,” he said. “There’s a divot here, trust me, I fell in it.”

The mother saw there was, in fact, a divot—proof that Valencia had indeed previously been there. He bent down and picked up two pebbles, brushing off the dirt before he handed them to the mother and her brother so they could leave them atop the tombstone, in keeping with Jewish custom.

“I’ll give you some time,” Valencia said.

Valencia waited a few headstones away until the mother turned from the grave and came over to him. The mother said her own mother was buried in this cemetery, but she could not remember exactly where.

Valencia asked for the name, inquired at the cemetery office and took her to that grave. He again picked up two stones.

On the day of the exhumation, Valencia kept watch as Leslie Zaret’s remains were lifted from the grave. He had by then spoken to so many of her relatives, friends and acquaintances that he felt as if he knew her.

“Leslie was a great kid,” he later told The Daily Beast. “Somebody you would want to bring home to mom.”

He reflected that a number of her close friends had gone on to get married and have children.

“Some of them now grandchildren,” Valencia said,

Leslie had all the while lain in this grave, forever cheated of her future, of even a moment past her murder.

In the meantime, the suspect had married and divorced and had children.

“He had a life, he had children, two marriages and this poor girl died at 17,” Valencia told The Daily Beast.

The remains were transported to the medical examiner’s office in Queens. A forensic anthropologist was able to recover some material from under Zaret’s fingernails.

As Valencia pledged, the remains were returned to the cemetery that day. A prosecutor who is Jewish said Kaddish, the Jewish prayer of mourning, as Leslie Zaret was returned to the earth with all the respect she was due.

“Even the grave diggers took their hats off,” Valencia told The Daily Beast.

After the sod was replaced atop the grave and the site was cleaned up, Valencia took a photo. He later showed it to the mother to confirm that everything was just as it had been, apart from a few more stones that he and the others had left atop the tombstone.

“You are a man of your word,” the mother told him. “Thank you.”

Unfortunately the fingernail scrapings did not contain enough DNA to make a match.

“It was a shot we had to take,” Valencia later said.

The Leslie Zaret murder has remained a prolonged and painful lesson in the difference between being all but sure, and actually proving. The suspect has never been charged and The Daily Beast is not identifying him by name. He would not agree to speak with a reporter or to provide somebody who could speak for him.

The suspect did tell The Daily Beast via email that he first learned of Zaret’s murder when he was interviewed by detectives during the initial investigation. He said that he fully cooperated. He noted that he was 20 years old at the time and was shocked by the details. The suspect added that he was “deeply saddened by the murder.”

He said the killing “unfortunately coincided with a totally different matter,” apparently referring to the sexual assault for which he was convicted and sent to prison.

With regards to the Zaret case, the suspect said he only knew that he “wanted the case solved.”

“And still do,” he told the Daily Beast.

Retired since 2007, Valencia noted that many detectives have one particular open case they had wanted to make more than any other.

“That was mine,” Valencia told The Daily Beast. “I wanted to bring that case home so bad. There is no doubt he’s my guy.”

Jaffe felt exactly the same. The three-star chief and the detective, were both pure cop at the core. She described herself as “disappointed but determined” when they could not proceed with an arrest. She remained hopeful that there will be justice for Zaret.

“We believe that people know who did the murder and need someone to come forward with the information that will lead to the conviction of the perpetrator,” Jaffe said.

Along with regularly conferring with Jaffe, Valencia had joined her in dreaming about the murder. He saw himself in a courtroom with Leslie’s best friend as the suspect was found guilty. He continues to hope that moment may yet come true.

Jaffe left the NYPD 2018. She returned to where she had started out, the 75 Precinct in Brooklyn. She made an entry in the log book:

“Chief Jaffe

Last tour

Started my career here in the 75 precinct—almost four years—loved every minute, the cops, the crime , the chaos. A tumultuous time in the city. Cops running, never slowing down… April 1984, fell in love with a little baby… Holding her, feeding her. Now 34 years later, she is my daughter. How blessed I am.

Loved being a cop 38 ½ years, proud to wear the uniform; honored to serve the city. I feel good about what I achieved. I met beautiful, dedicated and passionate people… I thank them all for everything they did and continue to do. God Bless you. God bless the NYPD.”

But really it had all begun with the desire to protect others after a teenage girl was found in a schoolyard just down the street from where Jaffe grew up.

Jaffe spoke of that girl when the time came for her to say a few words at her retirement party.

“Tonight, I want to remember her, because it is still an unsolved murder,” Jaffe said “We believe we know who did it and there are a lot of people who believe he did it, but there’s just not probable cause.”

The case had almost been broken as a result of Jaffe’s dream and Valencia’s hard work. The killer might still be brought to justice someday. There is always the chance that somebody will come forward with something critical they heard or knew all along. There is even a chance that somebody else will jolt awake with what proves to be more than just a dream.

“So let’s remember Leslie Zaret,” Jaffe said. “Aug. 17, 1974.”