European watering holes have been seducing writers for decades. A long afternoon spent writing (or supposedly writing) at a sidewalk café, usually accompanied by an apéritif, has a certain allure and draw. Ernest Hemingway wrote of his “good café” and extolled the virtues of “a clean, well-lighted place.” Malcolm Cowley pined for those days on the café terrace, “with a good long drink and nothing to do but drink it.”

And often, from the research I’ve done for my books, those writers enjoyed the bitter apéritif Campari and, naturally, included it in their novels, memoirs and poems.

The liqueur was invented by Gaspare Campari in the 1860s at the Bass Bar in Turin, Italy, where he worked as a maitre licoriste, or master bartender. Campari is a secret blend of natural ingredients, mostly herbs, spices, bark, fruits and fruit peels. Its distinctive carmine hue originally derived from dye extracted from the cochineal, a beetle-like insect native to Latin America.

One of the earliest literary references I have been able to find for Campari is in the work of D.H. Lawrence. While he’s best known for his classic (and controversial) 1928 novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he traveled extensively in Italy, and in 1916 published a set of essays titled Twilight in Italy. The final chapter, “The Return Journey,” contains a somewhat melancholy summation of his perspectives on Como and nearby Milan, and he perhaps uses Campari to express his bittersweet feeling. As for Como, he reckons that “it must have been wonderful even a hundred years ago. Now it is cosmopolitan …” and “everywhere stinks of mechanical money-pleasure.” Milan was no better; “sitting in the Cathedral Square, on Saturday afternoon, drinking Bitter Campari and watching the swarm of Italian city-men drink and talk vivaciously, I saw that here the life was still vivid, here the process of disintegration was vigorous, and centered in a multiplicity of mechanical activities that engage the human mind as well as the body.”

Coincidentally, it was in Milan where Ernest Hemingway discovered Campari, just two years after Lawrence released Twilight. At age 18, Hemingway served in the International Red Cross Ambulance Corps, and was severely wounded during an Austrian mortar attack on the Italian lines near Venice. Evacuated to a hospital in Milan, he spent the summer and fall of 1918 recovering from 227 shrapnel and bullet wounds to his legs. Friends would bring him wine and spirits to help him deal with his pain (and boredom). As he recalled in his memoir A Moveable Feast, one of these friends was an “old man with beautiful manners and a great name who came to the hospital in Italy and brought me a bottle of Marsala or Campari and behaved perfectly, and then one day I would have to tell the nurse never to let that man into the room again.” When he later recounted this tale to Gertrude Stein, she brusquely replied, “those people are sick and cannot help themselves and you should pity them.” Hmmm, but the old guy did have good taste in booze, no?

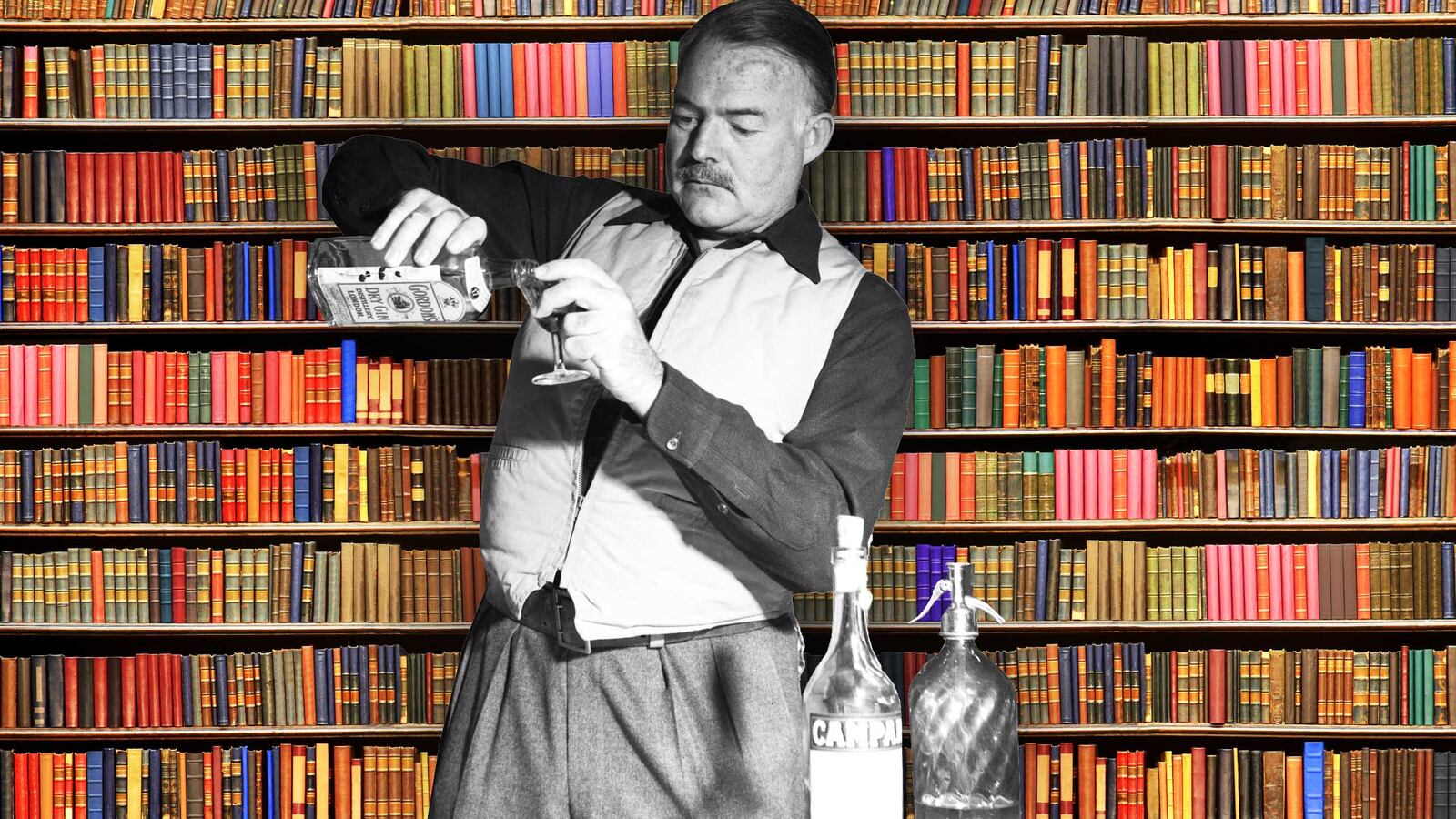

Campari can also be found in Hemingway’s 1949 novel Across the River and Into the Trees. It’s the tale of an aging army officer, Colonel Richard Cantwell, and his much younger lover Renata, having one last fling in Venice. Although he’s on heart pills and really shouldn’t be drinking, upon his arrival at the Gritti Palace Hotel, he’s cheered by the fact that his bellboy has taken the liberty of purchasing for him “Campari bitters and a bottle of Gordon Gin,” and asks the Colonel “May I make you a Campari with gin and soda?” How could the good Colonel refuse? “He did not want it, and he knew that it was bad for him. But he took it with his old wild-boar truculence,” perhaps a sly reference to the wild boar on the Gordon’s label.

In a later scene, Cantwell observes “a post-war rich from Milan, fat and hard as only Milanese can be, sitting with his expensive looking and extremely desirable mistress. They were drinking Negronis, a combination of two sweet vermouths and seltzer water …” While it sounds like Hemingway is confusing the Negroni (gin, Campari and sweet vermouth) with some kind of Americano (Campari, sweet vermouth, sparkling water), his heart was in the right place.

Another famous novelist and imbiber, Ian Fleming, was also a Campari fan. In fact, the first drink ever enjoyed by his signature character, James Bond, who is, of course, known for ordering a Vesper and his “shaken, not stirred” Martini, was actually the Americano. It makes an appearance in Fleming’s first Bond novel, Casino Royale, published in 1953:

“Bond ordered an Americano and examined the sprinkling of overdressed customers, mostly from Paris he guessed, who sat talking with focus and vivacity, creating that theatrically clubbable atmosphere of l’heure de l’apéritif. The men were drinking inexhaustible quarter-bottles of Champagne, the women Dry Martinis.”

Speaking of Paris, Fleming reveals his disdain for the City of Light’s cocktail scene in his 1960 short story “From a View to a Kill.”

“James Bond had his first drink of the evening at Fouquet’s. It was not a solid drink. One cannot drink seriously in French cafés…No, in cafés you have to drink the least offensive of the musical comedy drinks that go with them, and Bond always had the same thing—an Americano—Bitter Campari, Cinzano, a large slice of lemon peel and soda. For the soda he always specified Perrier, for in his opinion expensive soda water was the cheapest way to improve a poor drink.”

And in the 1960 short story “Risico,” Bond ordered another Campari classic during a clandestine meeting with Kristatos, a Greek smuggler and informant. They’d agreed to meet at the Excelsior Bar in Rome, and since the two men didn’t know each other, Bond was “told to look for a man with a heavy moustache who would be sitting by himself drinking an Alexander.” While Bond appreciated the ingenuity of using a drink as an identifier, he would never want such a “creamy, feminine drink” for himself. So, when the waiter appeared, “Bond nodded. ‘A Negroni. With Gordon’s, please.’”

After Fleming passed away, Kingsley Amis continued the Bond book series. While Amis acknowledged that Campari (by itself, presumably) was generally not his “cup of tea,” in his posthumously-published (and eminently enjoyable) collection Everyday Drinking, he admits that “hurray, an acceptable drink can be cobbled together” using Campari and “another innocuous potation” (sweet vermouth) and Pellegrino, resulting in the Americano. And “if it still lacks something,” he suggests, “throw in a shot of gin and the result is a Negroni. This is a really fine invention. It has the power, rare with drinks and indeed with anything else, of cheering you up. This may be down to the Campari, said by its fans to have great restorative power.”

And then you have those two other classics from the Americano family tree that are also connected with the publishing world, the Boulevardier (bourbon, Campari and sweet vermouth) and the Old Pal (rye, Campari and dry vermouth). The Boulevardier shared its name with a Paris-based features and gossip magazine from the mid-1920s, co-published by writers Arthur Moss and Florence Gilliam, socialite Erskine Gwynne, and nightclub owner/raconteur Jed Kiley. It was Moss who created the drink, and probably did the lion’s share of the writing.

And the Old Pal? It was invented by William “Sparrow” Robertson, who was called by Time magazine in 1941 “the most remarkable columnist of them all—the Paris Herald’s cocky, antique, legend-crusted, peewee…universally known as the Sparrow.”

He became one of Paris’ most prodigious night owls, and was known for calling his friends “old pal,” regardless if he’d known them for years or mere moments. Fortunately, the drink makes a lot more sense than his writing; his daily offering was characterized as a unique column—a syntax-slaughtering chronicle, which editors were carefully warned not to unscramble.

I’ll close with perhaps the greatest commentary on the Negroni, attributed to writer and Renaissance man Orson Welles. “The bitters are excellent for your liver, the gin is bad for you. They balance each other.” Works for me. Salute!

Negroni

INGREDIENTS:

1 oz Campari

1 oz London dry gin

1 oz Sweet vermouth

Garnish: Lemon peel or orange wedge or peel

Glass: Rocks

DIRECTIONS:

Add all the ingredients to a mixing glass and fill ice. Stir and strain into a rocks glass filled with fresh ice. Garnish with a lemon peel or orange wedge or peel.