Lawyers for the Portland romance novelist charged with killing her chef husband got their first chance on Monday to present a defense since she was arrested and charged with his murder more than three years ago.

At the heart of that defense: love. Nancy Crampton Brophy couldn’t have killed Oregon Culinary Institute chef Daniel Brophy, attorney Lisa Maxfield argued in a Multnomah County courtroom, because she loved him, and he her.

“The state will present a circumstantial case that begs you to turn a blind eye to the most important circumstance of all,” Maxfield said. "What circumstance is that? Love. Nancy Brophy was grateful. She had a husband who was adventurous, loving, playful and she knew that was a rare gift.”

Maxfield told jurors on Monday, the first day of what’s expected to be a 7-week trial, that Crampton Brophy would take the stand and speak for herself. She is charged with killing Brophy, who was gunned down on June 2 of 2018, shortly after he arrived to work at a school in downtown Portland where he worked as a chef and instructor.

Crampton Brophy’s arrest made national headlines after it came to life that she’d written a 2011 post, entitled “How to Murder Your Husband.” Before the jury of seven men and 12 women even entered the courtroom, Judge Christopher A. Ramras threw that salacious piece of writing out. “Any value in it is substantially outweighed by the danger of an article written that long ago of unfair prejudice and confusion of the issues,” Judge Ramras said, before the trial began.

That left Deputy District Attorney Shawn Overstreet without a juicy piece of circumstantial evidence in a case that leans heavily on circumstantial evidence: that Crampton Brophy researched gun kits in the month before the shooting; that the couple was having financial troubles; that the writer took out no fewer than 10 different life insurance policies in her husband’s name that would net her more than $1 million upon his untimely death; that even as the couple struggled to pay the mortgage on their suburban Portland house, they were still paying more than $1,000 in monthly premiums to keep those policies active; that surveillance footage showed her driving her minivan to and from the area where the shooting took place, just before and after Daniel Brophy took his last breaths.

“She executed what she perhaps believed to be the perfect plan when she ended the life of beloved chef Daniel Brophy,” Overstreet said.

That surveillance footage contradicted what Crampton Brophy told police when they interviewed her at the scene of the crime: that she’d gone back to sleep after her husband left for work that morning and stayed in bed until first driving to the crime scene a couple hours after the shooting. In a later phone call, Crampton Brophy had a favor to ask of a Portland Police detective: could he produce a letter clearing her as a suspect in the murder? One of the life insurance companies she was seeking payment from needed that, to process her claim.

While the state didn’t rely much on the accused’s writing, the defense did. After delivering a winding story about Crampton Brophy discovering that she needed eye surgery and then writing a letter to her husband detailing what to do if she didn’t survive it, Maxfield displayed text messages between the couple that demonstrated a happy marriage. Maxfield explained away the multiple insurance policies on Dan Brophy’s life as the product of smart retirement planning and Crampton Brophy’s fervent belief in the need for life insurance. Maxfield argued that the policies were evidence that Crampton Brophy had been betting on was her husband’s longevity, not his death, since one of the more expensive policies paid back all its premiums if he lived until 78. And Maxfield suggested that the difficulties in collecting on the policies after Dan Brophy was murdered meant that it hadn’t been in Crampton Brophy’s interests to murder him.

“Murder can be a huge complication when it comes to life insurance,” Maxfield said.

Maxfield acknowledged a “cash flow” problem in the year leading up to the shooting, but said the Brophies had a plan to subdivide their property and sell off parts of it, that money was coming from Crampton Brophy’s work selling Medicare policies, and that they both dreamed of spending less time working. As to the statements Crampton Brophy made to police the morning of the shooting, that she’d stayed in bed, Maxfield said she intended to present testimony from psychiatrists that the trauma of learning one’s husband has just been murdered might have a detrimental impact on a wife’s memory. “Learning her husband has been murdered is one of the most extreme shocks. A chemical floods the brain that disrupts the neurological coding, and that chemical disruption can leave large memory holes,” Maxfield said.

To the gun and gun parts Crampton Brophy researched and bought at a gun show and online, Maxfield offered a couple of explanations: that Crampton Brophy was working on a book about a woman who “flipped the script” on an abusive partner by killing him with a gun assembled from pieces bought online, for which the author needed to practice assembling and disassembling a gun. “Nancy Brophy always had several stories living in her head,” Maxfield said. Another rationale Maxfield offered for buying the gun: Crampton Brophy and her husband were jointly worried about the rise in mass shootings across America in 2017. A gun seemed like good protection.

Maxfield did not address in her opening the surveillance footage showing Crampton Brophy driving towards the crime scene just before the shooting and away from it minutes later.

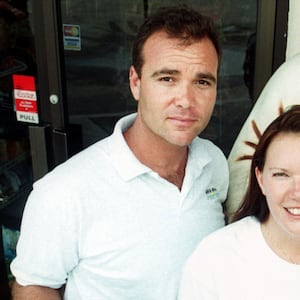

Dan and Nancy Brophy met while she was a student at the Culinary Institute, Overstreet, the district attorney, said, and “after enough convincing by Ms. Crampton, the two married in 1999.” They bought a house that year and lived in it until Dan’s death. The couple had no children together. Nancy worked as a caterer and sold life insurance to earn money, which her work as a romance novelist did not. Dan was a lead instructor at the school, while Nancy was “management” of the household. By 2016, they were struggling to pay the mortgage, and, but Crampton Brophy still found $1,500 to spend on guns and gun parts, and $1,000 on monthly life insurance premiums. “Nancy started researching and planning the murder of Dan Brophy,” Overstreet said.

She couldn’t assemble the ghost gun parts she bought online, Overstreet said, so instead she bought a different slide and barrel to fit the Glock she and Daniel bought at a Portland gun show. Twice, she went to a shooting range en route to the coast, where the prosecutor said that she likely practiced using the gun. Swapping out the slide and barrel would prevent forensic investigators from matching it with shell casings found at the murder scene, Overstreet said. The slide and barrel Crampton Brophy bought online were never recovered. “Nancy had everything she needed to carry out and conceal this murder,” Overstreet said.

After the shooting, Nancy’s neighbor told detectives “she seemed distressed, kind of frantic,” Overstreet said. “Nancy claimed she was looking for her dogs that had gotten out. The neighbor didn’t see any dogs.”

When detectives told Nancy her husband was dead, she responded “Yeah I got that, when everybody gave me the sad sack look,” according to a recording of that conversation played in court.

Later, Crampton Brophy called one of the police detectives: “I don’t want to be the stupid question of the day, but I think I need to be the stupid question of the day,” she said in a recording played in court. “My insurance company said just have the detective write a letter that says you’re no longer a suspect.”

“Why would you need that?” the detective asked.

Crampton Brophy replied “Because they don’t want to pay if I secretly went down to the school and shot my husband, as if I thought going into old age without my husband is something I’m looking for.”

The cop declined her request: “We would never do something like this.”

The first two witnesses after opening statements concluded were a former student and an instructor at the Culinary Institute, both of whom offered emotional testimony about discovering Dan Brophy’s body.

Kathleen Dooley was the first to call 911 after arriving at the school around 8 a.m. and hearing a fellow student yelling that someone needed to call authorities. “She said ‘there’s a body in here, there’s somebody on the ground.”

At first the call didn’t go through, then Dooley spoke to a dispatcher in a conversation played in court on Monday. The dispatcher asked if Brophy had heart issues, and upon learning someone else was doing chest compressions, told Dooley she was “doing a good job.” Dooley testified that she eventually went and kneeled next to the other student, who noticed blood seeping onto her hands as she pumped Brophy’s chest. “She thought she had broken a rib,” Dooley said. “I touched his arm, his hand. I put my hand on him.” Then she broke down crying.

Defense attorney Kristen Winemiller mostly asked Dooley about where things were in the school, but she also inquired about whether a homeless camp, which proliferate across downtown Portland, was nearby, and whether a homeless man had entered the school. “You are jogging some memory,” Dooley responded.

Instructor Dorothy Sadie Damon also provided emotional testimony, breaking down as she recounted the first moment she saw her colleague dead. “I went to Dan, and I knelt down beside him. I didn’t know what to do, so I held his hand. I wanted to see if he would squeeze it back, and he didn’t,” Damon said. She called her boss, “wailing,” and then went back into the kitchen. “It was obvious that Dan was gone,” she said, between tears. She told the student performing compressions to stop. “I didn’t want her to keep trying to do anything to save him. She was wearing herself out.”