If you have a recent impression of Ernest Hemingway, it’s probably Corey Stoll’s bombastic, scene-stealing, near-parody depiction of him in Woody Allen’s 2011 comedy Midnight in Paris. Stoll plays a handsome, young Hemingway in Paris in the 1920s—before Key West, before Havana, before the African safaris, before For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea, and before his second, third, and fourth wives.

In that film, Owen Wilson’s character is writing a novel about a memorabilia shop and asks Hemingway if it sounds terrible. “No subject is terrible if the story is true, if the prose is clean and honest and if it affirms courage and grace under pressure,” Stoll’s Hemingway says with earnest deadpan. Might Hemingway read the novel and render an opinion? “My opinion is, I hate it. If it’s bad, I’ll hate it because I hate bad writing. If it’s good, I’ll be envious and hate it all the more.”

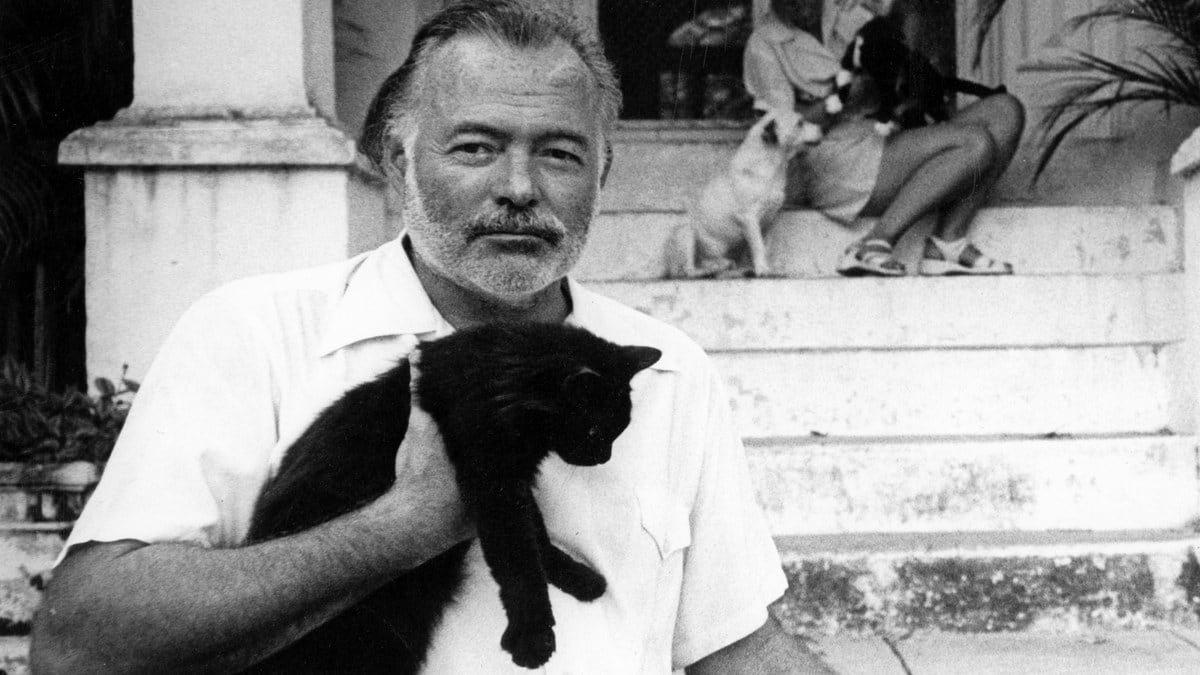

Because he was born in 1899 and found soaring celebrity a generation before TV news or Super 8 home videos, there are very few clips of the actual Ernest Hemingway with video and sound. When he was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954, an NBC News reporter interviewed a Hemingway who was unrecognizable from the dashing, declarative young journalist and author in Midnight in Paris.

In the interview, which you can watch on YouTube and which Ken Burns and Lynn Novick include in their new PBS docuseries Hemingway, he has lived and aged and declined into the more familiar Papa with a white beard and a guayabera buttoned over his wide midsection. Hemingway is cognitively infirm, stiltedly reciting his answers from offscreen cue cards and saying “period” and “comma” as he reads his responses to the questions. He is 54 but looks 74, and he would die of a self-inflicted gunshot wound seven years later.

“Something very new we’re discussing are the traumatic brain injuries that he suffered all throughout his life,” Burns said in an interview. “The very serious things that we now know cause the kind of things, the alcoholism and the drug addictions, that can add to madness and mania that he clearly had.”

Ernest Hemingway in uniform circa 1918. Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection.

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston/PBSHemingway had as many as nine concussions in his life—freak, random traumas induced by, among other things, a bombing in Italy during World War I and from two plane crashes in Uganda only months before the Nobel Prize—and likely suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain condition that results from repeated head trauma that has been diagnosed in many boxers and football players. Former NFL star Junior Seau knew he was suffering from CTE when he killed himself in 2012, and Hemingway suffered the same depression, cognitive decline, and suicidal thoughts that Seau and other retired athletes with CTE have experienced.

Both as a novelist and as a biographical subject, Hemingway is difficult to describe without many, many hands:

* On the one hand, he was an innovative prose stylist who brought pared, journalistic writing into literature in the 1920s and was a modernist figure and Paris contemporary of poet Ezra Pound, songwriter Cole Porter, painter Pablo Picasso, and filmmaker Luis Buñuel.

* On the other hand, he was a product of a privileged upbringing whose first two marriages were to women of inherited wealth, which gave him the time to travel the world and develop as a writer without the pressure to make a living at it for the first decade of his career.

* On the one hand, he wrote praised novels like The Sun Also Rises (1926), For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), and The Old Man and the Sea (1952) that received wide acclaim, burnished his reputation as a visceral, perceptive storyteller and made him a national celebrity with endorsement deals and his face on the cover of Time, Life, and Saturday Evening Post.

* On the other hand, he wrote panned clunkers like Across the River and Into the Trees (1950) and the posthumously published Islands in the Stream (1970) and The Garden of Eden (1986), the first of which prompted John Dos Passos to write, “How can a man in his senses leave such bullshit on the page?”

* On the one hand, prominent literary figures throughout Hemingway extol his deep sensitivity, his commitment to spending time with his family, and the well-rendered female characters in his novels and stories.

* On the other hand, Hemingway was sexist, anti-Semitic, used the n-word, was married four times, and became one of the most deplored animal-rights abusers in history by valorizing the horrific cruelty of bullfighting, and organizing African safaris where he killed hundreds of lions, cheetahs, gazelles, hyenas, rhinos, wildebeests, jackals, sables, kudus, and oryx to mount on his walls.

“When we began the project several years ago, we were very much aware of exactly the things you’re raising,” Hemingway co-director Novick said. “The questions of whether and how Hemingway was problematic and what that reflects about our society were questions we were asking from the beginning. Why should we be interested in him? We should have to justify that.”

Ernest Hemingway and his three sons (L-R: Patrick, Jack, and Gregory) on the Bimini docks. July 20, 1935.

Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston/PBSHemingway is unmistakably an attempt to reassert the author’s place in the 20th-century literary canon, but Burns and Novick do not shy away from telling you things that may—and in my case definitely did—move you toward the conclusion that Hemingway was more problematic than many celebrities who have been “canceled” in recent years. Midway through watching the series, I wrote in my notes, “I’m starting to get the sense that Burns and Novick don’t like Hemingway either.” When the facts are bad enough, objectivity becomes its own judgment.

The six-hour Hemingway ushers forward nearly two dozen novelists, historians, biographers, and one of Hemingway’s sons to support the proposition that Hemingway is immovably fixed as an immensely consequential figure in American history and world literature. Edna O’Brien, Abraham Verghese, Tim O’Brien, Mario Vargas Llosa, and others praise Hemingway’s literature and contextualize his actions.

There is no dissenting talking head in Hemingway, though, to say that he is a poster boy for toxic masculinity or that he should be associated as much with racially problematic colonialists like Rudyard Kipling as with modernists like Gertrude Stein. There’s no one to say that viewers who want to understand American history may be better served with a series about Muhammad Ali or the Great Migration or the Harlem Renaissance or the history of criminal justice in America.

Hemingway on the fishing boat Anita, circa 1929.

Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston/PBSOn the other hand—that again—Burns and Novick have covered the wider canvas of race, gender, war, sports, and culture in their previous documentary films and are working now, individually and together, on projects about Muhammad Ali, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance, and the history of criminal justice in America.

Hemingway was a visionary modernist who rescued literature from stuffy, florid prose and a freethinking globalist who brought an expansive worldview into American literature. He was also a drunk, a philanderer, a preening barbarian, and self-styled man’s man who steeped himself in increasingly weird and wholly fabricated stories about killing a hundred-plus bad guys when he was briefly a medic in Italy during World War I.

Ernest Hemingway recovering from injuries at the American Red Cross Hospital in Milan, Italy, 1918.

Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston/PBS“I believe that facts are facts and that there are truths that we tried to find and share,” Novick said. “There are so many points of view and so many ways of looking at Hemingway that we tried to get to know him from many different sides and let the audience decide.”