Indicted former President Donald Trump is currently on an extended episode of Law & Order—facing two people who lived through the real version of the drama.

The hard-nosed TV police procedural was originally inspired by the grim experiences of prosecutors at the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office during the tail end of a decades-long crime wave. The rookie class of 1994 saw it all, but two of those then-rookie prosecutors now stand out for a shared reason: They will both play decisive roles in historic criminal cases involving the former president.

One is Juan M. Merchan, now a New York Supreme Court justice who presided over Trump’s arraignment last week and is expected to oversee his trial next year for faking business records to cover up a hush money payment to a porn star.

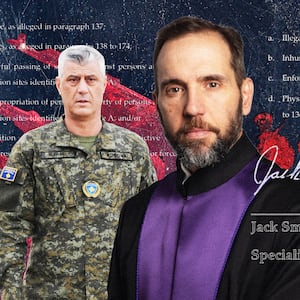

The other is Jack Smith, the Department of Justice special counsel currently using a federal grand jury in Washington to investigate how Trump lied to the American people and inspired his followers to attack Congress on Jan. 6, 2021—and then hoarded classified documents at Mar-a-Lago once he left the White House.

Merchan and Smith were classmates at the Manhattan DA’s Office, first-year lawyers who got their start just as Mayor Rudy Giuliani adopted the “broken windows” policing strategy—a severe crackdown on every imaginable minor crime under the theory that a steel fist would finally pound the cruising crime rate into dust.

Their fellow classmates told The Daily Beast that Merchan and Smith were reliable soldiers on the front lines of this new war on misconduct. That meant enduring shifts that sometimes stretched for two days at a time, late-night visits to multiple bloody crime scenes, and jumping into trials unprepared in a way that felt, as Shakespeare put it, like a daily return once more unto the breach.

”The training we got then—by virtue of the volume, pace, intensity—was something one could only get at that point in time,” said Georges G. Lederman, a former prosecutor who had been there for seven years by the time Merchan and Smith showed up.

Their boss was the legendary DA Robert Morgenthau, who ran that office all through the rising crime in the 1970s and 1980s, and then saw its precipitous drop over the next two decades. He was known for giving each incoming recruit a handshake with an accompanying line: “I ask of you only one thing: That is, to do the right thing.”

“Jack and I and everyone else were imbued with that one directive. That’s what we did, and that’s what he did,” Lederman said. “Jack stood out. He was a very methodical guy, very much a straight shooter. He made friends easily.”

At the DA’s office, recruits were split up into different bureaus—each with its own prestige and, at times, comical character. Former colleagues likened it to Hogwarts houses from Harry Potter.

The pensive and stoic Merchan, then a young father, was placed at Trial Bureau 60, which had a reputation for being cautious yet approachable. “They didn’t take themselves too seriously. Not zealots. Moderate,” one person recalled. It was the kind of formative experience that would perfectly suit a future judge.

Meanwhile, Smith went to Trial Bureau 30, known for a gung-ho attitude of taking on challenging legal battles against all odds that four different ex-prosecutors described as “scrappy.”

“Thirty was not afraid of a fight, or of a difficult case. They were not afraid of losing. It was a badge of honor to lose a case now and then, because never losing a case meant never taking a hard one to trial,” remembered another colleague, David Liston.

In those days, an overworked prosecutor with two simultaneous trials that afternoon would regularly walk by a fellow assistant district attorney in the Hogan building’s narrow hallways and ask them to suddenly take a case. That kind of handoff was dicey, because volunteering to fill in meant taking on a case without the valuable experience of having conducted the actual investigation—something that took a decent amount of grit and a leap of faith.

Smith was always up to the task, colleagues said.

Karen Friedman Agnifilo recalled being pregnant with twins, fearing that going to one particular trial was just too risky; the defendant had attacked police officers, court security guards, and threatened prosecutors, plus, there was a chance she’d have to interrupt the trial with a sudden trip to the hospital delivery room.

“Of course, who steps in and says, ‘I’ll do it for you?’ Jack Smith,” she recalled.

“He was someone you could rely on. Some people are always too busy, or always too important, or smarter than anybody else. He was humble, helpful, smart. He wasn’t a gunslinger. But he wasn’t afraid to go,” she said. “Some people just can’t pull the trigger. They get really scared. Jack wasn’t.”

The Manhattan DA’s Office, which pulled the case file on Friday, confirmed that it was Smith who successfully prosecuted Carl Davis, a man who court records show had carjacked a taxi and taken police on a chase through the city that ended when he slammed the car into an NYPD vehicle. Agnifilo recalled that Smith went above and beyond, hopping on a police chopper to get aerial pictures of the distance of the car chase to show in court just how far Davis had gone. Another former colleague noted that Smith was always “willing to stick his head above the parapet.”

“It was insane back then,” Agnifilo said. “You had to have guts. Trial Bureau 30 was known as being ‘Work hard, play hard.’ Sometimes we got four murders in a night. We just couldn’t keep up. We were playing whack-a-mole. We’d have 400 cases per ADA.”

After a long day, young and single assistant district attorneys would put aside their typewriters, clip on their beepers, and head to a local bar. As The Daily Beast noted in a profile of Merchan last week, the Colombian raised in Queens would ditch his friends and head home to his kids. Meanwhile, Smith would walk over to the Irish bar Baxter’s with his buddies and get a pitcher of cheap beer.

There was a lot to discuss over drinks. The pressure placed on rookie prosecutors in 1994 was extreme. Judges, defense lawyers, and even cops were annoyed at the way the DA’s office aggressively pursued criminal charges against repeat offenders for even the smallest infractions, like jumping the subway turnstile or shoplifting. It clogged the local courts and crowded the city jails.

“It becomes sort of a crucible. You get tested by fire. Some people can snap under those circumstances, but others become even more resilient. Juan and Jack developed a thick skin, patience, courage that are probably why they are well situated to do what they’re doing now,” Liston said.

Several former colleagues noted the poetic nature of having Law & Order prosecutors, straight out of Central Casting, aggressively cracking down on street-level crime, now involved in holding accountable a former American president who revels in turning the justice system upside down. There’s also a tinge of irony.

While Trump’s authoritarian style is generally adored by police—whom he’s encouraged to rough up detainees and commended for violent crackdowns on leftist protesters—the real estate tycoon has defied every law enforcement effort aimed at him by ignoring the New York Attorney General’s subpoenas and shrugging off judicial orders time and time again.

Merchan’s forceful-yet-composed personality was on display at Trump’s surreal arraignment in New York City just last week, when he warned the former American president to “please refrain from making statements that are likely to incite violence or create civil unrest.”

One of Trump’s sons responded by posting a photo of Merchan’s daughter—sparking concerns that she was being targeted for violence in the style of a collapsing democratic state—and Trump himself railed against the judge in a televised speech at Mar-a-Lago that night. Merchan also presided over a recent trial in which the Trump Organization was convicted of tax fraud. And it was Merchan who sentenced two affiliated companies to pay $1.6 million in fines in January.

But the world has yet to see anything concrete from Smith, who has operated largely in the shadows. After being assigned the role of DOJ special counsel by the nation’s attorney general in November, Smith has assembled a team of federal prosecutors to investigate the Trump White House and 2020 presidential campaign insiders, seeking to force former Vice President Mike Pence and others to testify before a grand jury whose work proceeds in secret. Legal scholars following the case expect there to possibly be a federal indictment later this year over his incitement of the Jan. 6 insurrection and hiding classified documents at home unprotected.

Merchan and Smith have drawn visceral hatred from the hardcore MAGA brigade, which breathlessly repeats Trump’s baseless claims that both are involved in mere political prosecutions. But former colleagues noted that they were both tough-on-crime prosecutors who employed the very law enforcement strategy so often heralded by Republicans. And friends said their arduous experience at the DA’s office prepared them to weather the flames.

“We’d get yelled at from morning to night by judges, and also defense lawyers, and even by the police sometimes. There were days when you thought, ‘No one really likes me any more and yet I have a job to do.’ You either quit, snap, or develop—as do soldiers, emergency room technicians, journalists—a commitment to doing what must be done,” Liston said.

Gene Porcaro, a retired lawyer who supervised Smith as the Trial Bureau 30 chief, said that the younger attorney’s performance in Manhattan’s criminal court—the very one where Trump now faces criminal charges—has prepared him now.

“A lot of people couldn’t, because it’s just nerve-wracking. He was able to handle pressure very well. He’ll do the right thing,” he said.

Agnifilo, who worked closely with Smith, added that he’s exactly the person you’d want doing this. “You want this process to have integrity, and he is the guy. That's it,” she said. “They picked the perfect person. He’s a prosecutor’s prosecutor.”