Mike Singh didn’t think twice about the wild-looking stranger who walked into the Burger King he managed at a Sacramento bus terminal in April 1995. The disheveled man with the matted mop of reddish-blond hair looked like all the other “bums” who came in in the mornings, Singh later told the Associated Press. The stranger, who ordered a breakfast sandwich, had several books tucked under his arm. He told Singh that he was doing research.

Singh would later see a photo of the man on television. His name, according to the news anchor, was Ted Kaczynski, and the FBI had just arrested him on suspicion of being the Unabomber, the serial-bombing bogeyman who had been terrorizing America for nearly two decades.

But the day of the arrest was still roughly a year away on that morning at the Burger King; and before he was finally brought to justice, Kaczynski had one final, deadly surprise in store.

Several days later, a shoebox-sized package arrived at the Sacramento offices of the California Forestry Association, wrapped neatly in brown paper. When Gilbert Murray, the organization’s 47-year-old president, opened it, the bomb hidden inside detonated, killing him.

The handful of staffers also in the office that day all escaped unharmed, but the office looked apocalyptic after the blast. One employee later told The New York Times that it had been like walking through “a war atmosphere, with shrapnel in the walls and everything busted down. There was a chemical smell from the bomb itself. The carpeting and all the walls had been ripped out.”

“There was a real sense of evil to it,” he added.

The same day, a letter was delivered to The New York Times. Its author claimed he was responsible for the string of 15 previous mail-bombing incidents that had taken place over the last decade and a half, proclaiming his goal to be nothing less than the complete “destruction of the worldwide industrial system.”

This was the shadowy figure known to the American public only as the Unabomber.

The Unabomber announced in his letter that he was preparing to send the Times and a few other news outlets a “long article” he had written, which he wanted published in its entirety. Acquiesce to his demands, he promised, and he would “permanently desist from terrorist activities.” Resist, and he would “start building our next bomb.”

Theodore John Kaczynski, a recluse who had spent 25 years eking out an existence in the Montana wilderness, was arrested almost exactly one year later. His 35,000-word manifesto, calling for a revolt against technology and environmental destruction, had indeed been published, sparking the chain reaction that finally led authorities directly to him.

Though Kaczynski was referred to as “the alleged Unabomber” in news reports, after glimpsing the mountain of evidence inside his cabin—including a copy of the manifesto, 40,000 pages of journal entries, and a fully-constructed bomb—one agent who had spent years on the Unabomber’s trail turned to his colleagues in tears.

“This is it,” he said, according to the Times. “It’s over. This is the guy.”

Kaczynski—who died in his prison cell on Saturday—would eventually agree to plead guilty to several charges linked to the Unabomber’s 17-year bombing campaign, which killed three people and injured 23 others. A Harvard graduate and the subject of the longest, most expensive manhunt in FBI history, Kaczynski was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole in 1998.

Before he became the Unabomber, though, Kaczynski was “Teddy,” a kid growing up in a working-class Chicago suburb. His father, Theodore “Turk” Kaczynski, was a sausage factory worker. His mother, Wanda Kaczynski, was a fixture at local PTA meetings, and frequently could be found leading bands of children through the woods, educating them about the environment. She read articles from Scientific American aloud to Teddy and his brother, David, seven years his junior.

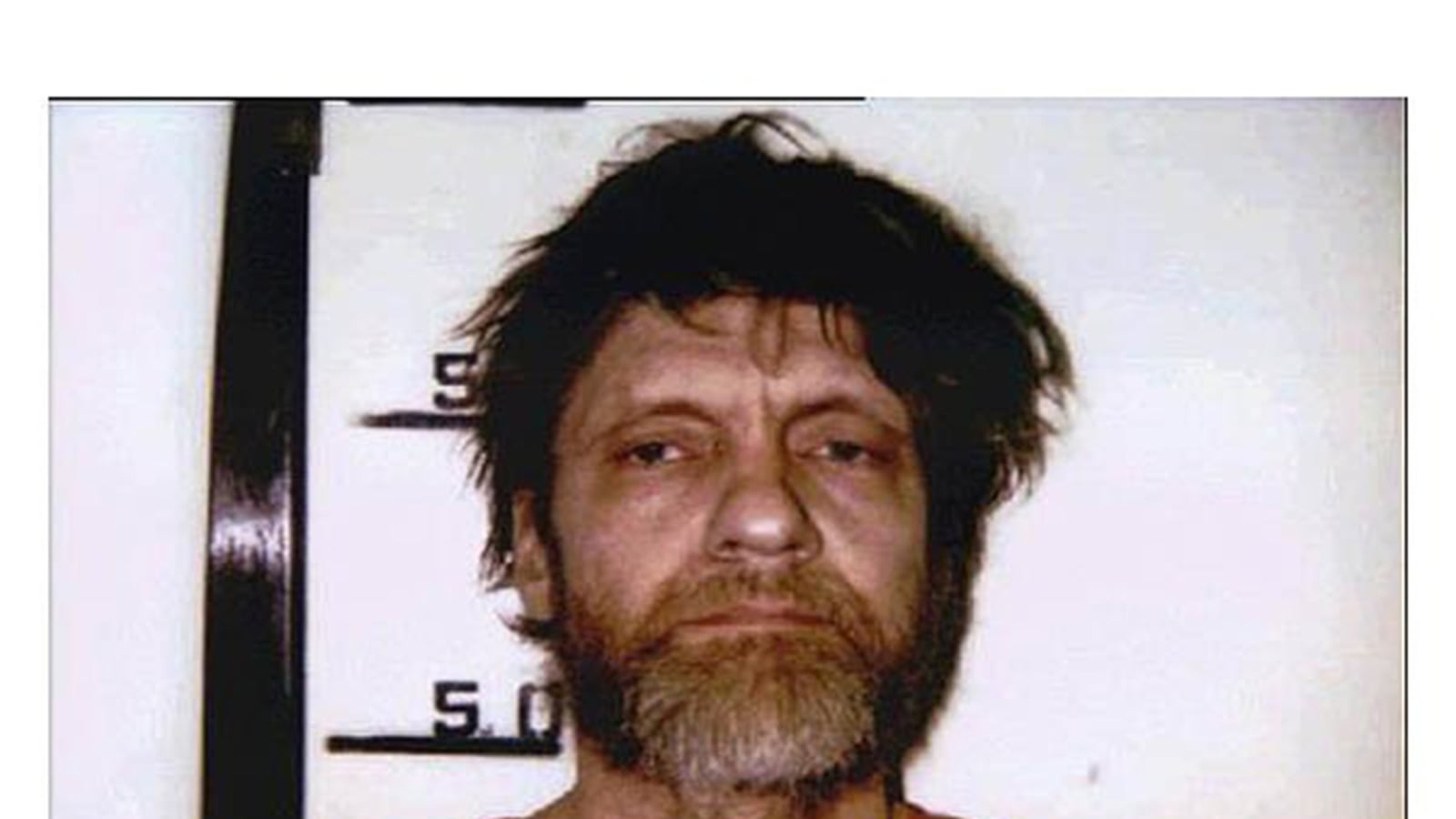

Archival photo of American mathematician and Professor Ted Kaczynski, later a domestic terrorist known as the Unabomber.

Scott Manchester/GettyBorn in 1942, Teddy was “a nerd’s nerd, shy and arrogant, socially doomed,” as a New Yorker writer put it. Given a “genius” score of 167 on a fifth-grade IQ test, Kaczynski was skipped straight to seventh grade, later jumping another grade on an administrative recommendation in high school. Two years younger than his peers, Kaczynski was a social pariah. He joined the chess, coin-collecting, German, and mathematics clubs; he was a voracious reader; he played the trombone. Nothing helped.

Scientifically minded, however, he did possess a preternatural talent for creating explosions that occasionally drew others in. Classmate Dale Eickelman later told Chicago’s Daily Southtown how, at 12 years old, Kaczynski “had the know-how of putting together things like batteries, wire leads, potassium nitrate and whatever.” The pair would go to the hardware store to collect materials for “things you might call bombs,” trekking to open fields to “blow up weeds.”

Kaczynski excelled academically, and enrolled at Harvard on a scholarship at age 16. “Of all the youngsters I have worked with at the college level,” his high school guidance counselor wrote to the university, “I believe Ted has one of the greatest contributions to make to society. He is reflective, sensitive, and deeply conscious of his responsibilities to society.”

At Harvard, Kaczynski would bolt past his housemates after classes, shutting himself up in his room to eat alone. The smell of rotting food wafted from his door, and his neighbors were often kept awake by his late-night trombone practice sessions, or the sound of him repeatedly banging a chair against the wall, rocking as he studied, according to a report from The Washington Post. Paralyzingly introverted, Kaczynski was now also afflicted with what he termed “acute sexual starvation,” as he later reflected from behind bars.

There was “something gnawing, something brewing” in Kaczynski by the time he graduated from Harvard in 1962, according to a criminologist’s assessment for the Post. Moving on to pursue a master’s and doctorate in mathematical analysis at the University of Michigan, Kaczynski had already begun to fantasize about “revolutionary violence” and “breaking away from normal society,” a court-appointed forensic psychiatrist later concluded.

But Kaczynski was an undeniable virtuoso in mathematics, his Michigan classmates said. “While most of us were just trying to learn how to arrange logical statements into coherent arguments, Ted was quietly solving open problems and creating new mathematics,” Joel Shapiro explained to the Times. “It was as if he could write poetry while the rest of us were trying to learn grammar.”

Parlaying his talent into a teaching post at the University at California Berkeley, Kaczynski appeared to be on track for tenure by 1969, when he quit with little warning or explanation. The Post reported Kaczynski had told his father, Turk, that he hadn’t wanted to teach students how to destroy nature with nuclear weapons. But an Atlantic writer later suggested that Kaczynski had only accepted the position to build up a nest egg for his inevitable retreat into the wild.

On a 1.4 acre plot of land in Montana’s high country that he jointly owned with his brother David, Kaczynski built the cabin that became his home for the next quarter-century. Living without electricity or plumbing, he grew or poached his own food, riding a rickety bicycle five miles into the nearby town of Lincoln every few weeks to quietly stock up on the bare essentials and visit the public library.

“I hate the system not because of some abstract humanitarian principle but because I hated living in the system. I got out of it by getting into the mountains,” Kaczynski told a documentary crew making a 2020 Netflix miniseries. “But the system wouldn’t leave me alone.”

Hypersensitive to the mechanical noise that intruded into his forest sanctum, Kaczynski in the early ’70s began to exact his “revenge,” as she called it, through “monkey-wrenching,” a nascent term environmental activists had plucked from an Edward Abbey novel to describe acts of industrial sabotage. He struck wires between trees on trails used by motorcyclists; poured sand into the fuel tank of a nearby sawmill; and attacked snowmobiles with engine-degrading sugar. There was less he could do about the jets that frequently screamed over his cabin, though.

Stewing in his rage, Kaczynski also began to distance himself from his “stinking family,” as he later wrote to David, around 1977. Turk and Wanda received long, hate-filled letters accusing them of pushing their oldest son too hard academically. He blamed them for everything—his social ineptitude, his failure with women, and his anger. “I hate you, and I will never forgive you, because the harm you did me can never be undone,” he wrote to Wanda in one scorching note, according to Time magazine. When Turk committed suicide in 1990, shortly after being diagnosed with lung cancer, Kaczynski skipped the funeral. After David got married in 1989, he became a target of his brother’s written ire as well.

The Unabomber struck for the first time on May 26, 1978. A strange wooden box—“meticulously sanded, polished and stained, like a piece of fine furniture from an old-world artisan,” as a Times writer described it—arrived at Northwestern University. A public safety officer opened it, detonating the crude, homemade bomb inside. The officer’s hand was injured in the explosion, but he escaped with his life.

Wanda Kaczynski and her son David Kaczynski are escorted to their car by defense lawyer Dennis Waks and attorney Anthony Pisceglie after the suspected Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski pleaded guilty.

John G. Mabanglo/GettyMore bombs began to be mailed out, seemingly to wreak havoc indiscriminately. The Unabomber’s victims would eventually include university professors, graduate students, computer store owners, a secretary, and a geneticist. In one 1979 incident, a dozen people were treated for smoke inhalation injuries after one of the Unabomber’s parcels caught fire in the cargo hold of an American Airlines flight from Chicago to Washington, D.C., though there were no fatalities. “The idea was to kill a lot of business people who we assumed would constitute the majority of passengers,” the Unabomber wrote in a 1995 letter to the Times. “But of course, some passengers would likely have been innocent people—maybe kids or some working stiff going to see his sick grandmother. We’re glad now that that attempt failed.”

Kaczynski responded to news reports of his other attacks with unbridled glee, however. After maiming an Air Force pilot studying at Berkeley in May 1985, Kaczynski mused in his journal that the victim might have been “one of the guys that has flown those fucking jets over my home. This gives great relief to my choking, frustrated anger and sense of impotence against the system.”

A joint task force made up of a number of federal agencies and a swelling FBI file on the “UNABOM” (for “university,” “airline,” and “bomber”) case did little to produce answers. The suspect meticulously erased his tracks, removing any traces of DNA from his bombs before sending them out. Desperate for leads, the bureau eventually offered a $1 million reward for information. More than 53,000 calls swamped the bureau. All of them pointed to dead ends, according to lead agent Donald Noel.

Meanwhile, Kaczynski’s bombs were becoming lethal. In December 1985, Hugh Scrutton, 32, was killed after picking up a bomb filled with nails outside the computer rental store that he owned. “Excellent,” Kaczynski wrote in his journal. “Humane way to eliminate somebody. He probably never felt a thing.” In December 1994, one of his bombs killed 50-year-old Thomas Mosser, a New Jersey advertising executive. “A totally satisfactory result,” Kaczynski concluded.

The Unabomber began to speak publicly for the first time in 1993, beginning a one-sided correspondence with newspapers like the Times, the Post, and the San Francisco Chronicle that reached a crescendo in June 1995, when he mailed out his colossal manifesto, expecting publication in a “widely read, nationally distributed periodical.” (The publisher of Penthouse offered in an open letter not only to publish the manifesto verbatim, but also to give the bomber a monthly column.)

“The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race,” Kaczynski began his 56-page manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future. He insisted that people had been robbed of their freedom, happiness, and dignity by the techno-industrial state. The only solution was revolution, violent if necessary, and the system’s wholesale annihilation. “In garrulous print, his credo revealed him to be a visionary,” a New Yorker critic proclaimed in 1997. “His dream was of a green and pleasant land liberated from the curse of technological proliferation.”

The manifesto was published by The Washington Post as an eight-page supplement on Sept. 19, 1995, following three months of deliberations with both Attorney General Janet Reno and FBI Director Louis J. Freeh. Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr. of the Times, who had been involved in the discussions, fronted half of the printing costs. “Here we are dealing with an individual with a 17-year record of violent actions,” he said on publication day. “Hard experience proves that his threat to send another bomb… must be taken absolutely seriously.”

David Kaczynski first read his brother’s manifesto in October, scrolling on a library computer in Schenectady, New York, with a sinking feeling. It was his wife, Linda Patrik, a philosophy professor at Union College who had never met Ted, who first seriously suggested that there might have been a link between the man in the woods and the mysterious Unabomber. “Hey, you’ve got this screwy brother,” she had joked in the past, David later recalled in an interview. “Maybe he’s the guy.”

On an emotional level, David told ABC News, the manifesto “just sounded like my brother’s voice. You know, the way he talked, the way he argued, the way he expressed an idea.” He and Linda dug out a number of Kaczynski’s old letters, including a vitriolic 23-page essay in which he fumed, “Technology has already made it impossible for us to live as physically independent beings.” The couple, chilled, spent several months comparing the evidence and discussing whether to come forward with what they were increasingly convinced was true.

David and Linda eventually approached the FBI in December 1995. Kaczynski was arrested by federal agents on a cold, slushy day in April the following year. Though the bureau had promised them confidentiality, David turned on his television that night to see CBS’ Dan Rather explain to viewers across the nation that the alleged Unabomber had been turned in by his own brother. Kaczynski himself found out the next day, when he asked a public defender in Lincoln how he’d been caught. “Oh, didn’t you know?” the lawyer replied, according to Yahoo News. “It was your brother.”

Kaczynski was hauled before a Sacramento court to answer for a number of the Unabomber’s attacks, including two of the fatal bombings. Though David, accompanied by Wanda, had a seat in the packed courtroom ten feet away from his older brother, Kaczynski never once acknowledged his family. Instead, he initially pleaded not guilty, and appeared set to go to trial—until he learned that his lawyers were preparing an insanity defense, attempting to save him from the death penalty.

This kicked off what the San Francisco Examiner diplomatically called “a long-running disagreement with his defense team regarding his mental state.” For months, Kaczynski clashed with his attorneys, who were planning to call experts to paint him as dangerously, schizophrenically disconnected from reality. They had hired a flatbed truck to haul his 10-by-12 foot plywood cabin across the country to the courtroom, a New Yorker writer covering the proceedings reported, where they would “show it to the jury and ask the question: ‘Would anyone but a certifiable lunatic choose such a primitive abode?’”

Desperate to avoid a humiliating trial, Kaczynski asked the judge to be allowed to either hire new legal representation or represent himself. Both requests were denied. After an attempt to strangle himself in his cell failed, Kaczynski concluded he had been backed into a corner, and agreed to a plea deal in January 1998, all but directly acknowledging he was the Unabomber.

Kaczynski s guided to his arraignment in Helena, Montana on April 4, 1996.

Michael Macor/GettyAs Inmate 04475-046 at a federal supermax prison in Colorado known as the “Alcatraz of the Rockies,” Kaczynski lived on “Celebrity Row” alongside the Oklahoma City bomber and one of the men behind the 1993 World Trade Center attack. He told a pen pal that he thought both were “nicer than the majority of people I’ve known on the outside,” according to Yahoo News. In fact, he wrote in another letter, he considered himself “to be in a (relatively) fortunate situation” in the lockup, he shared in another letter.

“And yet the knowledge that I'm locked up here and likely to remain so for the rest of my life—it ruins it,” he told a Time magazine writer, who judged the Unabomber to be “affable, polite and sincere,” in 1999. “And I don't want to live long. I would rather get the death penalty than spend the rest of my life in prison.”

Though he remained a prolific writer behind bars, corresponding with the hordes of people, including multiple love interests, who wrote him letters, and penning a number of books, Kaczynski soured on interviews after the Time profile. With hardly any information publicly available about his activities over the last two decades, it came as a surprise when the Federal Bureau of Prisons announced in December 2021 that Kaczynski, then 79, had been transferred to a medical center “known for treating inmates with significant health problems,” according to The Washington Post. A bureau spokesperson declined to share details on his condition.

“There has never been a serial killer in the United States with Kaczynski’s academic credentials,” one article trumpeted the week of Kaczynski’s arrest. But Linda, speaking candidly a few months after her brother-in-law’s sentencing, downplayed his twisted achievement. “Based on this whole experience, I have lost respect for tremendous intellect,” she said. “I have discovered that genius needs to be coupled with heart and loving relationships with people to have a positive impact on society. I now know that intellectual brilliance alone has great dangers.”