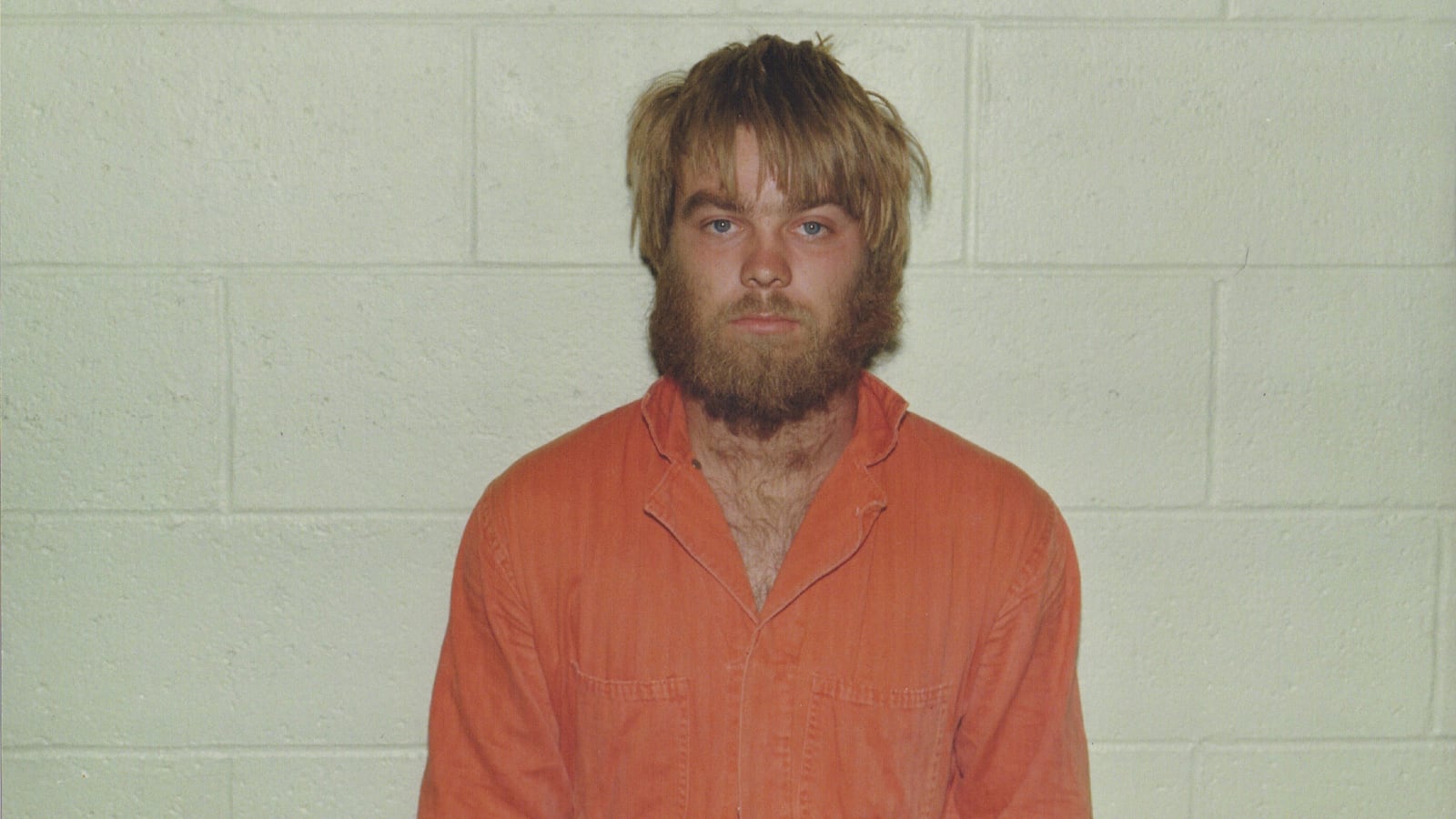

You think you’ve got lingering questions about Making a Murderer, Netflix’s 10-part documentary about wrongfully convicted Wisconsin man Steven Avery and his eyebrow-raising 2007 trial for the murder of photographer Teresa Halbach?

Writer-directors Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi spent a decade whittling down over 700 hours of footage to craft the docuseries that’s turned viewers into Internet-sleuthing conspiracy theorists since it hit the streaming service on Dec. 18—and even they still wrestle with The Big Question: Did Avery do it?

“What I learned from making this series is the humility to accept that I don’t know, and I may never know,” Demos told The Daily Beast over the holiday break that she and Ricciardi properly hijacked, filling newsfeeds and social media streams with the shocked, angry, and outraged reactions of viewers making their way through Making a Murderer.

“That was one of the things we learned doing this: Just because you have questions doesn’t mean that you’re going to get an answer,” she said. “If you’re so committed to finding the truth and finding the answer, it’s very hard to be comfortable with ambiguity and you’ll often settle, just for some finality.”

The directors were NYC graduate film students when the saga of Steven Avery first caught their attentions, splashed across national news headlines. Avery, a working-class local with a record from Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, had been exonerated by DNA testing in 2003 after spending 18 years in prison for a rape he didn’t commit.

Two years later Avery was a high-profile pebble in the shoe of the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department, which he was suing for $36 million—the same authorities who eagerly locked him away again when the murder of a local woman led them right back to Avery’s door.

After reading a story in The New York Times about Avery’s plight, filmmaking (and romantic) partners Demos and Ricciardi borrowed a camera and hit the road to Manitowoc County in a rental, set on staying for a week to document Avery’s trial. As the case wore on they moved in to temporary digs in town, scoring key access to Avery’s beleaguered family by writing a letter to Avery, who gave his blessing from behind bars. The trial lasted six weeks and took an unexpected turn when Calumet County District Attorney Ken Kratz held a press conference that threw a sensational wrench into the case, and into Demos and Ricciardi’s plans, just as they were packing up to head home.

Avery’s 16-year-old nephew Brendan Dassey was arrested four months after his uncle, having implicated himself in the rape and murder of Halbach. Taped footage of his confession provides Making a Murderer with one of its more troubling elements, suggesting that Dassey was railroaded by investigators and his own counsel into spinning a fantasy version of the Halbach murder after repeatedly denying his involvement in the crime.

“One of the things I hope viewers who really engage with the series will take away from this is this question of, if they have lingering questions, are they comfortable living with that?” said Ricciardi. “There are now two people who are behind bars, probably for life. Do our viewers feel satisfied with the process that led to those convictions?”

The filmmakers had no idea how vast the scope of their film would grow when they first began the project, seeing in it a provocative case study of how the American legal system treated one man, twice accused.

“Here was a man who in 1985 was wronged by the system,” Ricciardi remembered. “It failed him and here he was, 20 years later, pulled back in. The question really was, had there been any meaningful progress within those 20 years? Would the system be any more reliable in 2005 than it was in 1985?”

In 2003, advances in DNA testing exonerated Avery of the rape of Penny Beernsten. But in 2007, after science saved him once, it damned him as prosecutors leaned heavily on FBI laboratory testing for a substance called EDTA in a blood sample that, Avery’s defense argued, had been tampered with.

“I think it really begs the question of the role of science in our criminal justice system,” said Demos. “Our system is made up of human beings, and human beings are muddy and complex and flawed, as we all know. Science is this very tempting black-and-white sort of thing. It’s tempting to believe that there is what some refer to as a ‘truth meter.’ You have DNA and we often get asked, ‘Was there DNA evidence proving he did it?’ We like to think that any kind of evidence, whether it be DNA evidence or any other kind, would just be the beginning of the inquiry, not the end of it.”

“I remember in this process beginning to understand that science and criminal justice, it’s very dangerous to put them together,” Demos continued. “Our criminal justice system is based on a presumption of innocence until you’re proven guilty—whereas in science, something is true until it’s disproved. So it’s exactly the opposite. We have one kind of test after another that used to be relied upon being revealed to be not so reliable, and there’s a problem there.”

Some have wondered why Avery’s defense didn’t fight harder to discredit the FBI’s EDTA testing, a method that had been used 10 years prior in the O.J. Simpson case. But as Avery laments to his mother, Dolores, by phone early in the series, “Poor people lose all the time.”

If Avery’s team had as many resources available to them as the state had at their disposal, Demos says, they might have been able to put the FBI’s test under more scrutiny. Instead, “the only thing the defense was in a position to do was analyze the data coming out of the FBI labs,” she said. “They didn’t have the funds. The FBI is a huge resource that the state was given—it would have cost tens of thousands of dollars.”

“In one interview that didn’t end up in the series, [Avery defense attorney] Jerry [Buting] talks about how they would have basically had to go to a university lab, ask them to do a research project to find out about degradation in EDTA, all of these things,” Demos explained. “So really, science was not at the place where it could be used to test this—and yet it was presented in court.”

Making a Murderer sheds a light on Avery’s case as his defense team of Buting and co-counsel Dean Strang mount an impassioned case for their client in and out of court, letting the filmmakers document their progress as well as their frustrations with the case, the headline-hungry media, and the public servants who fail and foil Avery and Dassey time and again.

The unassuming middle-aged lawyers with killer courtroom swag and eloquent quotables have become modern-day Atticus Finches for the millennial generation, noble defenders of justice who have unexpectedly amassed fervent fan followings of their own.

“We have some sense of that,” Ricciardi laughed. “Sometimes people email or tweet things to us.” She credits Strang and Buting with infusing Making a Murderer with the streak of principled outrage that marks the series. It’s easy to see how the dynamic duo have rubbed off on viewers with heartfelt lines like those uttered by Strang, who reacted to Avery’s conviction by lamenting, “Redemption will have to wait, as it so often does in human affairs.”

“There are ways in which people have asked us, ‘Is this series biased? Is it one-sided?’” she said. “What I would say in response to that is that we had very articulate subjects on the defense side. They were passionate. They believed in their client. And they were in a position to advance this theory that their client had been framed, and framed by law enforcement. So yes, we documented that. Yes, it’s in the series. But that was their opinion, and their role as advocates that we simply showed.”

But don’t mistake Strang and Buting’s perspective for the filmmakers’, she cautions: “It does not mean that we adopted it or that our interests were completely aligned with theirs.”

Although Demos and Ricciardi carefully guard their thoughts on Avery and Dassey’s guilt or innocence in interviews, at times in the 10-hour series one might infer the filmmakers’ real sentiments in how they frame the colorful cast of local reporters present at trial. An incredulous press conference inquiry here; a telling side-eye glance there. Making a Murderer condemns the breathless media reporting of local and national news organizations for their role in ensuring that Avery and Dassey couldn’t possibly find an untainted jury pool of their peers, even as Demos and Ricciardi present the local reporters they worked alongside for months as a Greek chorus foil to the prosecution.

“The reporters very much are window characters,” said Demos of the press pool, which had only heard the state’s version of events until the defense launched their arguments at trial. “The courtroom was the first place they were hearing the defense. They were very gracious and very open to collaborating with us, but at the same time they were also part of the story. And yet they had a different job to do and different access—they had access to the state but they didn’t have access to the family, so it’s a different story that emerges.”

Then there’s Kratz, the oft-smug, portly District Attorney who easily emerges as Making a Murderer’s villainous, mustache-twirling personification of The Man. Kratz declined to be interviewed for the film and earns a memorable coda when the series notes the unrelated sex scandal that got him fired after the Avery case. He publicly decried the series after its debut, and after irate fans bombed his Yelp page with negative reviews. More pointedly, he took to the media to slam Demos and Ricciardi for not including crucial evidence in their film that helped a jury convict Avery.

“You don't want to muddy up a perfectly good conspiracy movie with what actually happened, and certainly not provide the audience with the evidence the jury considered to reject that claim,” Kratz told People, citing evidence he presented in court, including *67 calls Avery made to Halbach and her reported discomfort at visiting the Avery Salvage yard after an incident in which Avery allegedly answered the door in a towel.

While in prison for the 1985 rape he was later cleared of, Avery “told another inmate of his intent to build a ‘torture chamber’ so he could rape, torture and kill young women when he was released,” Kratz said. “He even drew a diagram.”

“We wrote a letter to Ken Kratz saying who we were, and that we were interested in including as many points of view as possible in the series,” Ricciardi said. “We offered [Kratz] the opportunity. We offered it to the Halbach family. We offered it to Penny Beernsten, who was the victim in the 1985 case, Tom Kocourek who was the Sheriff, Dennis Vogel, and other members of law enforcement.”

Demos and Ricciardi say time constraints made it necessary to focus only on the evidence introduced in court that they deemed to be most crucial to Kratz’s case against Avery.

“There were clear pieces of evidence that the state was hanging their case on—the most incriminating pieces of evidence, whether it was that [Halbach’s] car was found on the Avery Salvage property or that her burned remains were found in the burn pit outside of his window, or a bullet fragment in his garage that had Teresa’s DNA on it,” Ricciardi argued, citing the limited screen time she and Demos planned to devote to the Halbach trial. “In the three or so hours we had to cover the trial, we had to pick what we perceived to be the state and the prosecution’s most incriminating evidence against Steven. And those are what we put in the series.”

“I think any of the [pieces of evidence not included in the series] are less incriminating than any one of the things I just listed,” she added. “As filmmakers and as storytellers, it’s in our interest to show conflict and to show the strengths of the state’s case, then show the defense’s arguments against it. That was how we structured things.”

The filmmakers maintain that the Avery case was never as cut-and-dried as Kratz would still have the public believe. “I would add that in closing arguments, Ken Kratz argued to the jury, ‘This case is clear. There’s only one reasonable outcome,’” Ricciardi said. “Dean Strang’s retort was, ‘Nothing in this case is clear.’”

Since debuting on Netflix, Making a Murderer has incensed viewers into action, sparking several meticulously detailed subreddits dedicated to the Avery and Dassey cases and spurring rumors that hacker group Anonymous might unleash the elusive pieces of evidence that could potentially exonerate the two men, who are serving life sentences for the Halbach murder. A Whitehouse.gov petition calling for President Obama to pardon the men based on the Netflix series has garnered over 15,000 signatures, while a Change.org petition has 82,000 and counting.

Strang, eloquent as ever in recent interviews, says that the Avery case still haunts him—and that the release of the series has generated new leads that could give Avery a second chance—again.

Making a Murderer mania has also led to the proliferation of conspiracy theories about who really killed Halbach, and whether shady scheming on the parts of friends and family of both Halbach and Avery contributed either to her death or the planting of evidence orchestrated to frame Avery.

At first, Demos and Ricciardi chuckle at the thought of incensed viewers deep-diving down online rabbit holes, hell-bent on uncovering the truth of what happened the afternoon of Halloween 2005, when Halbach disappeared after visiting Avery’s family salvage yard on assignment for Auto Trader magazine.

But Making a Murderer fanatics have dug more deeply into the case than the filmmakers ever anticipated, and the series’ arguable empathy for the Avery clan has brought more than just Kratz into the Internet’s sights. The directors very seriously caution against impassioned viewers jumping to conclusions to indict any of the “characters” of Making a Murderer, in the court of public opinion or otherwise.

“We always hoped that there would be viewer engagement, we just had no idea that people would become amateur sleuths,” said Ricciardi. “I guess it’s just the times we’re living in. But in terms of people zeroing in on particular individuals, we would just ask that people check themselves because part of the problem we saw—not only in the 1985 case, but I would argue as well in the 2005 case—was an incredible rush to judgment. And members of law enforcement are not the only people who can do that, and make that mistake.”

She and Demos are heartened by the emotional reaction viewers have had to the story of Avery, Dassey, Halbach, and their tormented families on both sides of the case. “But we’re hoping that that emotional reaction can lead to people doing something that’s actually constructive, and not destructive. We don’t want the series to harm other people who were subjects in it, or who played a role in it somehow.”

Demos and Ricciardi are still in contact with and recording Avery, who is in prison for life without the possibility of parole. They stress that Avery’s story is just one of myriad tales of men and women lost within and condemned by an imperfect American judicial system.

“These are things that are happening in every county in this country,” Demos said. “We hope that the dialogue gets beyond this case, and beyond Manitowoc County. I think that would be an opportunity squandered if the dialogue did not broaden to look at what the broader things going on here are.”

“We consider this an American story,” added Ricciardi. “An American story that happened to play out in Wisconsin.”