Wednesday, August 24, 1977

Thing was, none of them had given much of a fuck about Elvis while he was alive.

When you got right down to it, all Dead Elvis meant by the last week of summer was a congested Memphis, what with all the out-of-towners and news vans bunched together at the gates of Graceland to pay their respects and leave behind bouquets and teddy bears. Shit was everywhere, just take a look on the TV.

What they were always saying—fifty thousand Elvis fans can’t be wrong? News claimed over thirty thousand of those fans showed up, just to wait in line, see his body laid out at the Memphis Funeral Home. Rumor was that a few of the Beatles had even flown in all the way from England. Burt Reynolds and Ann-Margret, too. President Carter had to call in the National Guard, for Chrissakes.

Raymond “Bubba” Green wondered who was supposed to clean up all that shit. Taxpayer money, or cons handed Graceland details as Community Service.

To Bubba, there was only one thing that Dead Elvis meant: money.

The way the man from Cincinnati told it, it sounded like the King of Rock and Roll was worth more dead than alive—or at the very least, his body seemed to pay by the pound.

Bubba Green, who at 25 had been expelled or suspended from every school he’d ever attended throughout Tennessee, had grown accustomed to a life in and out of county lock-up, usually for selling drugs or for using them. By August 1977, he had grown more than accustomed to living for heroin, the same drug that had killed his Rhonda less than a year ago.

They’d met right after Bubba’s stint in Angola, that Louisiana state penitentiary named for the plantation and cotton fields that once occupied the land. Never married but thick as the thieves they were long enough for the State of Tennessee to label them as common-law. It had been Rhonda turned Bubba on to the harder drugs—the chipping—Bubba first figuring if she was going to be doing it, better she be supervised than unsupervised.

While Bubba was finishing up another jail stint, Rhonda took off for Dallas. When he was sprung, Bubba got word she’d been raped and killed in a roadside motel room, left to be found the next morning by housekeeping.

“We was not as good for each other as we should have been,” Bubba told people later, “but regardless, you know, I loved her.”

Back on the street by August of ’77, Bubba hadn’t much time for grieving. Let the world mourn Elvis, let him mourn Rhonda when he could. He had bonds to make, and Rhonda had taken what little money was left when she split for Dallas.

Bubba was thinking about just that—the girl, the money, the debt—when Blue Barron called him up Wednesday afternoon.

“Bubba, you looking to make some money?” Blue was a local bondsman Bubba had come to know all too well. He knew Bubba was looking to make some money, knew he was always looking.

“Good,” said Blue. “Meet me at the Luau.”

Like everyone in Memphis, Bubba Green knew the gaudy, Polynesian-themed exterior of the Dobbs House Luau on Poplar Avenue. Its sugary, fake island food was cheap and popular with the local college kids and the students from East High School across the street. He parked his motorcycle and, once inside, let his eyes adjust to the dim lighting of the large dining area.

Tiki torches flickered around the tourists lined up at the buffet. Mounted wood carvings shaped into sinister grins and framed stills of Elvis in Blue Hawaii were mounted along the walls. Blue Barron was seated at a family-sized wooden table under hanging plants and bamboo tufts. He was sitting next to another man. This one Bubba didn’t recognize. White, looked big, husky, although he was sitting. Both men had their hands folded on the table top. They watched Bubba walk in and waited while he pulled his trucker cap low and sat down across from both. Neither spoke until Bubba was settled.

“Are you interested in making a million dollars?” It was the big one beside Blue, the stranger. He said it more than he asked it.

Bubba didn’t know if he’d heard that number right, looked at Blue, who just nodded.

“I am mostly certainly interested in making a million dollars,” Bubba said.

There was a pause before the large man leaned in. “Well, what would you do for two million dollars?”

Bubba could hear it now in his speech—he was definitely a Yankee. “Well, sir,” Bubba said, “my mama ain’t safe for two million dollars.”

The man said he was from Cincinnati. Just about all he said, so Bubba thought of him as just that—Mr. Cincinnati.

Bubba Green followed Mr. Cincinnati down Union Avenue to the Holiday Inn, the one in walking distance to Beale. There, he parked his bike on the side, saw the man lumber up the metal staircase leading up to the second story of the two-story hotel, then unlocking the door to one room and standing outside the threshold for Bubba to see him. “Got any weapons on you?” Mr. Cincinnati asked, raising Bubba’s arms up in a frisk just inside the door.

“Yessir, a knife,” Bubba said, making eye contact and slowly handing over a butterfly knife from his right back pocket.

“Wait here,” the man said, pointing for Bubba to take a seat on the edge of the sparse room’s twin-side bed. Bubba folded his hands on his lap and studied the green carpet and the ugly gold geometric shapes in the design, the white Venetian blinds, the writing table: an ashtray loaded with Mr. Cincinnati’s cigarette butts and a small Holiday Inn stationery pad and matching pen. Crumpled balls of the stationery littered the desk.

He listened to the sounds of Mr. Cincinnati in the bathroom, not sure what was going on inside but hearing movement like the shower curtain being slid, followed by some exhausted grunting. The man emerged, each hand clutching an identical brown suitcase. He tossed both onto the bed behind Bubba’s back. “Look here,” he said, flipping a case open.

Bubba stood beside him, on his toes to crane over the larger man’s shoulder. He stepped aside for Bubba to see: maps and large, full-color photographs, mostly aerial views of Shelby County. It was easy for him to make out the shape of Memphis, the grid of its arteries punctuated by the muted tint of bayous and the blue wall of the Mississippi River to the west. There were more papers stacked underneath, and Bubba caught on to the bold type at the bottom of one enlarged, color map. Forest Hill Cemetery. The name was familiar, Bubba remembered it from the news.

Mr. Cincinnati pulled out tighter diagrams of the cemetery property, these with hand-drawn lines linking A and B points. White tape lines met at a specific mausoleum in the center.

The man began to sift through the other contents, handing Bubba papers in bunches, explaining as he went along. There were copies of receipts for a casket weighing 948 pounds; a nine-pound brass lock made special in Oklahoma City; the dimensions of a large, plexiglass bubble. “Take a look through these,” he said. Bubba leafed through the stack and the man bent to open the other case. “Look here,” he said and lifted the lid.

Bubba’s eyes nearly teared up. He was looking down at stacks of paper-belted hundred-dollar bills, each belt marked with “1,000” in black, felt-tip pen.

Before Mr. Cincinnati uttered another word, Bubba had already decided the money had to be counterfeit. All that cash in one place? Had to be fake. If not, this meeting was some kind of sting, Blue setting him up for another skip of his, needing an easy fall-guy. Who did he know, or who had he borrowed from who could rope him into some RICO thing?

Bubba had served enough time, he decided he’d never be anyone’s fall-guy.

But he also considered the bills looked real enough to pass along on the street. Rent, smack, bonds, and a ticket out of Memphis.

He felt Mr. Cincinnati’s eyes on him, watching him look down at the money. If all that money is real, Bubba now thought, this Yankee is carrying it around, he ought to be more afraid of more than just my little old knife.

“I’m going to ask for 10 million dollars in ransom for the body,” the man said. He was cool, calm, and collected—even the way he said the words like “ransom” and “the body,” like they was everyday words in a normal, everyday sentence.

Right in that there briefcase was a million dollars in belted bills, Mr. Cincinnati explained. It, along with another briefcase just like it, he went on, was all Bubba’s—but only if he could execute a single task: smuggle the body of Elvis Aaron Presley out of its final resting place—the little cemetery just off Elvis Presley Boulevard.

Forest Hills Cemetery, Lot #796A; about four and a half miles from Graceland.

The mausoleum constructed for Elvis Presley was a massive building, more than double the size of the single-family shack in Tupelo, Mississippi, that had been his childhood home. This was a monument—airy rooms housing six vaults, a palace of many chambers. Elvis’ was the one directly to the left, Corridor Z: 9 feet long and 27 inches high. All white, columns and tile. You walked in, all you heard was your own footsteps and breathing, the echoes of eternity billowing throughout a maze of granite and marble.

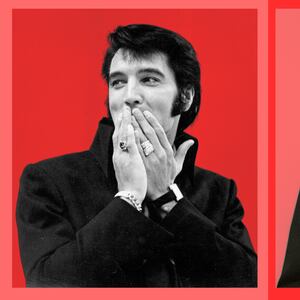

On August 18, the burial started with a long procession down the street bearing Elvis’ name—a white hearse leading 17 white limousines, all booked at a moment’s notice by Elvis’ daddy, Vernon Presley himself. Police had to carry away screaming fans attempting to charge his son’s hearse on foot. The copper coffin, weighing nearly a thousand pounds, was carried by the six people who were the closest the performer had to friends: road manager Joe Esposito, members of Elvis’ entourage, the self-proclaimed “Memphis Mafia,” and Dr. George Nichopoulous—“Dr. Nick”—Elvis’ longtime personal physician, known to get the King anything required for nearly twenty years of maladies: road fatigue, dehydration, high blood-pressure, and the twisted colon that brought on the fatal heart attack.

A small service was held at the mausoleum for a select group of family and professional VIPs, those who had known Elvis Aaron Presley in real life. They, too, were enough in number to line up for hours. Vernon was the last out, kissing the coffin and promising his famous son that Daddy would be with him soon.

Vernon saw to it that Elvis was buried wearing a white suit and a blue shirt, and had personally brought his son’s beloved TCB ring into the mausoleum to slide on his finger. Between the booking of the limos, the custom casket, and the all-important emblematic ring, Vernon had demonstrated that his son wasn’t the only Presley who could take care of business in a flash. Nine-year-old Lisa Marie helped her grandfather place a metal bracelet on her father’s lifeless wrist. Lastly, before the crypt’s gates were locked, a cylinder with Elvis' name, birth, and death dates was placed in the casket, ensuring easy identification during the Rapture. Elvis hated waiting in lines.

The crowd long gone, five workmen then cut through the three-thousand floral bouquets strewn among the lawn and entered Elvis’s tomb. They went in pushing a wheelbarrow full of sand and carrying a five-gallon bucket of water and cement, churning into a double slab of concrete to seal the crypt. They then covered it all over with a large marble sheet, Elvis’ name and lifespan to be chiseled later.

Like every other newscaster in Memphis, Russell Ruffin covered the death of Elvis Aaron Presley, just as he had covered every related update to come out of Graceland since word of the death first broke. That day, Russ and his crew had been two hundred miles outside Memphis, covering a routine legislative meeting that dispersed as soon as a civic employee entered the boardroom to announce Elvis had just been pronounced dead over at Memphis Baptist. Russ led the caravan back to WMC-TV Memphis’ Midtown studios on Union Avenue.

After moving down from Nashville in late 1975, the 36-year-old Ruffin learned quickly that working for the NBC Memphis station would mean covering just about anything having to do with the city’s favorite son. Not that he was complaining; Russ had grown up an Elvis fan himself, seeing Jailhouse Rock in theaters as a kid and painting sideburns on the sides of his face, strutting them around school before puberty allowed the real thing to grow in.

Around the newsroom, Russ was privy to all the Presley gossip that long predated the death. It had been rampant throughout Memphis pretty much Elvis’ entire career, as he’d bought Graceland only a year after signing with RCA in 1957. Superstardom in a year, and with it, one of those heavenly mansions Jesus mentioned.

Russ was quickly told the one about Elvis presumably breaking up a real bar fight right here in town, telling a shocked drunkard, “Why don’t you pick on someone your own size?” just like in one of his own movies. He then followed up on sightings of the King flying over Graceland in a private plane, surveying his kingdom below and amused at the sight of the crowd, unaware he was watching from above. Russ had looked into rumors Elvis had nearly been arrested for driving a go-kart down Elvis Presley Boulevard, saved only from the indignation of handcuffs by flashing the badge given to him by Richard Nixon. Elvis always had it on him.

And then there were all the Cadillacs. Russ covered each of those, too.

Russ had arrived in Memphis just in time to cover the third of Elvis’ widely-publicized stays in Memphis Baptist Hospital, always under the banner of road fatigue or exhaustion. The truth about the prescription drug addiction would only come out later during Dr. Nick’s trial—the scandalous affair finding Nick forever branded a pharmaceutical rubber-stamp for high profile patients like the late Presley and his darker contemporary, Jerry Lee Lewis.

It was during that stay in Memphis Baptist that the King got the bug to bestow his riches upon select members of an adoring public. See, if Elvis saw you on TV and didn’t like you, he’d pull out the small revolver always in his right boot and blast a hole right through the screen projecting your moving image. But if he saw you and he liked you, liked your face, then Elvis would pick up the gold phone—the one next to the couch—and dial a few numbers, have a new car sent to your house. That July, he’d bought a total of 13 Cadillacs from the local Madison dealership, then sent them out to random worthy citizens throughout Memphis. With love, Elvis Presley.

Or so Russ had heard. He was still working as a general correspondent for the network, hadn’t made weekend anchor just yet, the day Elvis called up the station room and asked for him by name.

Russ snatched the phone from his station manager’s hand, immediately recalling the one about Elvis buying some lucky Denver news anchor a brand new Eldorado—his reward for airing a “human interest piece” on him, making the performer sound more like Mother Teresa.

“Mr. Ruffin,” an unfamiliar voice spoke back to him. “Joe Esposito here. Mr. Presley is next to me and he really enjoyed that piece you did… You did a great job demonstrating his generosity…”

Presley had handed the receiver to his loyal road manager before Russ could get on the line. Insult to injury: the Cadillac wasn’t for any WMC-TV anchor. No, Elvis wanted the address for a girl Russ had interviewed earlier that day, one going through hard enough times she deserved a new Eldorado.

“You wouldn’t happen to have her address, now would you, Mr. Ruffin? Elvis sure would appreciate it.”

Might as well get a story out of it. Russ had grabbed a mic and a cameraman, rushed to Memphis Baptist anyway. They got as far as Elvis’ private door, eye-to-eye with an off-duty cop and Esposito himself. He haggled for a few minutes of taping, promising a piece for that evening’s broadcast: something about the outpouring of flowers, cards and, yes, teddy bears, all Elvis’ fans had been sending.

Good enough for Esposito, but Elvis was a little too tired at the moment to talk to the camera. Russ ended up reporting from beside the door, while over his shoulder, Elvis’ bare feet dangled off the edge of the bed, out-of-focus.

That was a year ago. By August 1977, Russ had earned a second title as weekend anchor and was a recognizable face around Memphis. Recognizable enough for an FBI informant to obtain his home phone number, letting him know someone was planning to steal Elvis Presley’s corpse later that week.

Thursday, August 25, 1977

Two days wasn’t all that much time for Bubba to plan for such a large-scale body-snatch, but it looked like Mr. Cincinnati had done his homework, making it all that much easier. He had a few names to get the ball rolling and would use his own promised payment for deferred expenses—including the team he would need. Giving it some thought, he had the makings of a skeleton crew before the day was out.

He knew a safe-cracker, one who owned a set of cutting torches that could get through the mausoleum’s iron railing. If memory served, Mike also had his own acetylene torches and oxygen tanks, like those scuba divers go out in the islands. Over the phone, he had tipped Bubba to an appliance store downtown, said they didn’t keep such a close watch on their loading docks early in the day. He could hotwire one of the appliance trucks—would be ideal, pick up whatever the hell it was Bubba needed help lifting.

He promised Mike 75 grand but considered upping it to as much as an even hundred if all worked out and Bubba was feeling generous. He considered the fact they still needed two additional sets of hands to get the casket from the crypt and into the truck box. Two more workers meant further dipping into Mr. Cincinnati’s briefcase. But Bubba had seen on the news that it took four pallbearers to carry Elvis’ casket; scaling back to only four was pushing it, he knew, but no way around it. He’d have to pay off three.

There was another old boy from the neighborhood, always needed cash for junk. Bruce Nelson was five years older than Bubba. They had scored together, for a while during the Rhonda years. They hadn’t spoken since Bubba had come back to Memphis, but he called him up, offered him 40 grand right over the phone. Maybe 60, same conditions as Mike.

Counting it out in his head, Bubba told himself he wasn’t necessarily being greedy. If he was in line to score two million for putting everything together, no reason he was expected to give it all away. He considered the outstanding bonds, the ones Blue Barron knew this type of one-time score would cover, and then some.

After that, Bubba thought, he would contact a few smugglers he knew from Angola. They’d be heading to the Caribbean once they got out, he remembered, and remembered the offer was open to sail along. Get him far away from Memphis and its ghosts.

For that, Bubba needed every cent he could squeeze.

Bubba ended his Thursday night with a beer, knowing he had a well-equipped box man in place, and some needed extra muscle. All he needed now was a wheelman, the getaway driver to high-tail them out of the cemetery, allowing Mike to casually join the other truckers on the freeway, their thousand-pound cargo secure in the box.

Bruce suggested Bubba contact Ronnie Lee Adkins. Bubba recognized the name from high school. They had never been friends, Ronnie was a year behind.

Bruce vouched for him, handed his home number to Bubba.

Friday, August 26, 1977

“Want to tell me where we’re going?”

Ronnie Lee Adkins, behind the wheel of his beige Chrysler, Bruce Nelson in the passenger seat. Bubba Green sat alone in the back, watching the storefronts and street signs along Elvis Presley Boulevard through the window on his left. Ronnie looked up at the rear-view mirror, waiting for a response.

“Just drive and I’ll tell you where to go,” Bubba said, not looking up when he said it.

Ronnie Lee Adkins had been the first to show up at the chosen meeting point—the parking lot of a laundromat on Union—his Chrysler idling as Bubba and Bruce pulled up along either side on their bikes. The men got in silently, Bruce finally saying, “How’re you, brother,” once the doors were shut. From the backseat, Bubba studied the back of Ronnie Lee Adkins’ head, watched his hands stay gripped on the wheel even while parked. He thought this was a good sign, a solid first impression. He didn’t mention the fact that he recognized Ronnie from school.

Bubba determined not to reveal to Bruce or Ronnie exactly where they were going just yet. Both had agreed to the job based on the money, tonight’s mystery tour being part of the deal. He was playing close to the chest, and that’s exactly why his plan—cobbled together in less than 48 hours—was going to work out just fine. He was playing it smart for once. Hell, he’d only needed Mr. Cincinnati’s map of the cemetery interior and the casket schematics. Other than that, Bubba knew the streets of Memphis good as anyone else.

So far, it looked like Ronnie Lee Adkins did too—and he took directions just fine. Bubba told him to turn onto the expressway, then sat back and folded his hands in his lap. He watched the Memphis streets pass by, all lit up, as quiet as the city gets, then went over the steps again in his head.

Mike would be sitting tight in the appliance truck on Route 69—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Expressway—waiting in the shadow of the Kerr Avenue underpass just west of the cemetery’s rear entrance. His industrial cutters and locksmith gear were stashed in the truck’s cargo box, along with a mobile generator just in case the truck’s battery couldn’t supply enough juice to drill through the concrete.

As soon as Mike saw the Chrysler, he would park at Forest Hill’s west entrance, while the other three went around to Elvis Presley Boulevard on the east side. They’d hop the fence on either side of the property, then Mike would use his flashlight to help them all meet in the middle. According to the map, Elvis’ crypt was in the center.

Only Mike was told the last part of Bubba’s 48-hour plan. First thing tomorrow morning, he’d call the man from Cincinnati through Blue Barron, have him meet in the parking lot of Poplar Plaza Shopping Center just after dawn.

Mr. Cincinnati, Bubba told Mike, would be bringing those briefcases—both of them.

Ronnie took the car onto Elvis Presley Boulevard. Again he looked up into the rear-view mirror. “Where from here?” he asked.

Eyes still out the window, Bubba mumbled to keep circling around Kerr Avenue and Hernando Road, keep a lookout for the appliance truck.

Half a dozen passes already the last half-hour. No Mike. No truck. More circles. An hour passed. Bubba tugged on the brim of his trucker cap. Where the fuck was he?

“You got a way to call your boy, check in on him?” Ronnie asked.

“Naw,” Bubba said, giving a quick glance away from the passing streets. “He don’t get that truck, we just try again tomorrow.”

Ronnie looked over at Bruce for a response, got nothing. He turned south on Hernando, all three men in the car glancing to their right, checking for a big, white truck one more time. Again nothing, just the darkness of the overpass shadow.

“Bubba, I gotta ask you,” Ronnie said, one arm over the other on the wheel as he made the turn passed Forest Hill’s iron gates. “We been circling Elvis Presley’s cemetery for any particular reason?”

Before he’d been handed a seemingly never-ending stream of Elvis Presley assignments, Russ Ruffin’s usual stories included community affairs and local politics. Both areas went hand-in-hand with the Memphis crime beat, ensuring not only the guards at Graceland knew Russ’ face on-sight, but so did the cops and bailiffs at the Shelby County Criminal Justice Center, local District Court, and the Tennessee Court of Appeals.

He’d always dealt well with law enforcement. Back in Nashville, Russ had covered the local police’s acquisition of their first Kevlar vests. The broadcast got him an invitation to the Press Club’s Gridiron show, an annual event for statewide news VIPs, all gathered together in a grand ballroom to rib each other, safely out of the public eye. Taking the stage, Russ demonstrated the bulletproof vest using a starter’s pistol.

Word spread about Russ’ Press Club appearance, and he got coerced by a network cameraman to recreate the stunt out in the studio parking lot. The cameraman was itching to test out the station’s new video camera unit and already had a gun in the trunk of his car. They loaded a blank, but the velocity of the blast—all the finite debris hidden in the fresh Nashville air, instantly ignited and shot at the speed of sound—sent Russ reeling, slamming him against a brick wall.

The clip found its way onto one of Dick Clark’s blooper specials. So far, that was the extent of Russ’ national exposure.

He moved to Memphis the following year, having taken enough bullets for one team. That November, he dodged a larger one. A few buddies linked through his NBC affiliate invited him to French Guyana, where they were covering California Congressman Leo Ryan’s visit to the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project—“Jonestown.”

Russ knew it was a big story and packed his bags. He made it to the airport but missed his flight. None of his buddies returned.

After that, covering news out of Graceland didn’t seem so bad, or covering the Memphis crime beat. It was never boring, and there were benefits to all the sheriffs knowing who he was, he could be trusted. Russ ended up with a lot of tips that way, all the cops and robbers both recognizing his face.

Like the first week of August, when Russ and a cameraman were on a routine assignment outside Shelby County Court.

He had his shirt-sleeves rolled up, the mic in his hand, watching the fresh arrests being escorted out of the courthouse. After all these months, Russ had started recognizing some of the faces. One in particular looked familiar—a white twentysomething male, sporting a day’s-old scruff and a dirty pair of jeans and tee shirt. Looked like a drop-out, his long hair falling down his face.

The kid stopped right in front of Russ, leaned in close to his ear. “Hey man,” he whispered. “Don’t use my picture.” He nodded to the cameraman. “I’m undercover.”

He hadn’t seen him since, but Russ never forgot a face. Or a voice.

The last Friday of August, Russ was home with his wife. Penny had dinner ready just as soon as he had walked in, and they were already clearing the plates when the kitchen phone rang. He wasn’t expected back at the station until early the next afternoon and was looking forward to a quiet night at home.

“Is this Mr. Ruffin from the TV news?” The man’s voice was familiar, but Russ couldn’t place it. “I had to get your number from the station,” the man said. “I told them I had an Elvis story for you.”

Another Elvis tip—it never seemed to end.

“Well, sure,” Russ said, looking over at Penny drying the dishes alone. “How may I help you, sir?”

There was a pause on the line before the caller spoke again. “Well, you helped me out a few weeks back and I thought I’d help you out now, too—you know, with a story.”

Russ craned over to the countertop and reached for a pen and small pad, the phone cord twisting around his body. “And how is that? I helped you out?”

“You were at Shelby Court a few weeks back,” the man said. “I asked you not to use my picture. I was undercover, working with Memphis PD…”

There it was, the drop-out with the hair. “Of course.”

“Well,” the man continued, “my name is Ronnie Lee Adkins. You were good to me, and I want to give you a scoop on something—something going down at Forest Hills Cemetery tomorrow night.”

Saturday, August 27, 1977

If this Adkins fellow was telling the truth, Russ considered, that gang of misfits better be strong—and be bringing plenty of gear for the heavy lifting.

He had said as much to Penny, placing the phone back in the cradle and reading her his notes from the strange phone call. For the past two weeks, Russ had covered the death of Elvis Presley from every possible angle, including the interment at Forest Hill. He knew intimately the near-impossibility of anyone getting through those gates, let alone driving off with a casket of that weight.

He turned to Penny. “These fellas would need a crane to pull this off.”

Russ also knew from contacts within the Memphis PD that Shelby County deputies were working in rotation, guarding the mausoleum itself.

He hadn’t enough time to wait for Saturday’s shift. Right after the call with Ronnie Lee Adkins, Russ dialed his closest squad contact, Captain Tommy Smith. “Listen, Tommy, I just want to make sure that you guys are aware of this,” Russ had said. “Before I run with this, I need to make sure I’m not holding any information that could get one of your boys hurt.” He repeated everything he’d been told by Ronnie Lee Adkins. When he was through, Smith’s answer surprised him enough that Penny froze cross the room just seeing his own reaction.

“Yep, the grave robbery?” Captain Smith had said. “We know all about it.”

Russ called ahead to his station manager at WMC-TV Memphis studios and requested a crew for a live feed later that night.

While working in Nashville, it was routine to chase down hot leads with the use of 16mm film; as an anchor here in Memphis, Russ now benefited from access to the NBC affiliate’s more modern equipment, namely its expensive live van. Still, he’d have had to call dibs on it, since there was only the one for the entire network.

By the time he punched into his Saturday shift, Russ been on the phone with Memphis PD all day, pumping the officers for updates and keeping his name associated with the exclusivity of the story. The latter had proved easier than expected: “You know, since I brought this to you guys, I was hoping we would be allowed to get up close, watch the arrest…”

The cops had agreed, but by Saturday afternoon, even they weren’t sure of the break-in’s possible time. They’d heard from their informant, but there had been no word on the time.

Not knowing didn’t endear the story any further to Russ’ station heads, none of whom wanted their only mobile unit wandering the streets of Memphis with no guarantee of a scoop.

Russ made a deal with the manager: the station’s best cameraman, Bernie, drove a white Crown Vic—one that could pass for an unmarked squad vehicle. Russ grabbed him on his way out the door at 9 p.m. He’d ride to Forest Hill Cemetery with Bernie, and the mobile van would follow behind.

Russ looked at his watch. He had the live crew for an hour and a half. After that, any grave robberies would have to be taped and edited for a later airing.

Climbing into the passenger seat of Bernie’s Crown Vic, Russ tuned the newsroom’s communal police scanner to the familiar Memphis PD frequency, prepared to sit back and listen intently for signs of life.

He told Bernie to head towards Elvis Presley Boulevard.

Bubba Green had no choice but to consider the previous night’s attempt as a dry run; no reason to tell the others it was a bust. At least now all three knew the lay-out: the streets and the checkpoints.

It was nearly midnight when, again in the backseat of Ronnie Lee Adkins’ Chrysler, Bubba finally spotted the appliance truck in the shadow of Route 69.

Bubba had felt furious all day. Seeing Mike in place at the underpass, the anger finally began to subside. He hadn’t been able to get him on the phone until late last night, Mike apologizing, going on and on that the appliance store employees had still been working the loading dock late into the night. He couldn’t have lifted any of the trucks until today, he insisted, but tonight should be fine. Sorry, brother…

He had Mike recite the plan back to him over the phone, then quizzed him on the smaller details. Satisfied, Bubba hung up and called the other two, letting them know tonight was a go.

Ronnie careened off of Hernando Road south towards Forest Hill. Bubba turned his head and watched the headlights on the appliance truck flash on and off, as Mike took off the opposite direction, north on Person Avenue.

They’d worked it out so Mike would bust his way into the cemetery through the back. He’d find Elvis’ massive mausoleum first, then signal the others with his military high beam. The assortment of cutting tools would be more than enough to bust the iron gate and all that marble—but they’d still have to cut their way through the fence to haul the casket itself out and into the truck.

There would be no way to cut through that undetected while they were inside doing their business, as any passing car would see the truck waiting by the west entrance. Bubba figured they’d have to bust it last on the way out.

Ten minutes to midnight. Bubba leaned forward, pointed to the coming turn street. “Pull up right here like last night,” he said to Ronnie, then to both Ronnie and Bruce, “Wait here—I’ll hop in first, make sure Mike’s in place.”

Bubba pulled his cap low on his head as he exited to the roadside. He looked around, then hopped the cemetery fence.

Russ knew he was losing his chance at a live feed after the first half-hour had passed. It was too quiet, parked there in Bernie’s car outside the Forest Hill gates, even with the staccato bursts of muffled directives shooting from the scanner. With the car radio off so they could listen to the police communications, it was the first time Russ hadn’t heard so much as a second of Elvis music in the past two hours.

“Russ, did you hear that last part?” Bernie reached over and turned up the scanner’s volume nob.

“What did I miss, Bernie?”

“A Chrysler was just pulled over near the cemetery… I think I heard an officer on the two-way ask his dispatcher if an undercover was in the car.”

Russ bolted upright. “What did he say?”

“Very possibly.”

It had to be them. Russ rolled down the window of the Crown Victoria and saw Hernando Avenue coming up ahead. “We’re going to lose the van any minute now,” he said, his voice against the wind. “Let’s head towards the cemetery and keep an eye.”

Bernie was back on Elvis Presley Boulevard in five minutes. He turned off the ignition.

It was nearly 10:30 p.m. “Bernie,” Russ said, “let’s keep that scanner cranked until they call back the van.”

Bubba hit the ground running.

He’d instructed Ronnie to turn the car off, not let it idle. Best be safely inside the cemetery and set up with Mike at the crypt before hollering for the others. Scaling the cemetery’s gate was easy enough, Bubba landing on his hands and one knee bent. The felt the grass cool under his hands and through the rips in his jeans. He looked up into the darkness and the sea of headstones. His eyes adjusted, and the stones slowly glowed a dull, pale gray against the black of the grass and the towering oaks and maples over a century old. Mike’s flashlight would be simple to spot through the 200-acre abyss.

According to Mr. Cincinnati’s aerial schematics, Elvis’ mausoleum should be west from his entrance over the fence. Staying low to the ground, Bubba looked around, inching his way towards the cemetery’s center.

He froze in place. Was that movement up ahead? Bubba didn’t see the beams of a flashlight, nothing but the dark swaying of the trees against the lighter darkness of the sky. But he could swear something had moved among the darkened shapes up ahead.

Finally, a light—a flashlight.

Mike setting up camp at the wrong fucking grave…

He watched then as the small white beam vanished—then appeared again, off to the left. He froze again. It was unmistakable—now there were two flashlights.

Either Mike wasn’t alone, or it wasn’t Mike at all.

There was no more time for silence: Bubba turned around on the spot, burning his knees against the ground as he scurried back towards the fence a hundred yards away.

“Bubba!”

He looked up, seeing the outline of Ronnie and Bruce in front of the gate’s railings and against the lights of the street behind. They’d climbed their way inside, were both whooping and hollering, their hands in the air, making a scene.

“Bubba!” Ronnie called out again, his hands cupped to his mouth. “Don’t move, man! Something’s wrong—we ain’t alone!”

Bubba climbed to his feet and ran towards the fence, noise and chaos be damned. “Run, boys!” he yelled, following behind as all three hopped back onto the street and made for the Chrysler. Ronnie ran around and took his place behind the wheel, gunning the engine before all the doors had slammed shut.

“Just go, man,” Bubba barked. “Go straight and just keep on goin’!”

Ronnie took a right onto Person Avenue instead, lightning fast.

“What you doin,’ man?” Bubba cried. “I said straight!”

Didn’t matter now. The beige Chrysler pulled onto Person, stopping short just as the inevitable came into the view for all three men: a barricade of at least half a dozen black and whites, all flashing their red and blue lights and cutting off any chance of passing through.

With them was an NBC news team.

For the better part of the last two hours, Russ had sat in the passenger seat of Bernie’s car, fidgeting with the wire of his mic, twirling it around his fingers like the tail of an animal. Every few minutes, Bernie double- and triple-checked the video camera on his lap.

As expected, the station had called back the mobile van. That was almost an hour and half ago. As they watched it drive off back to the network studios on Union, Russ and Bernie made themselves comfortable, both fearing a long stakeout.

Finally, five minutes after midnight, the fuzzy voice of a police two-way: “It’s going down.”

“Let’s move!” Russ said, unspooling the microphone wire between his fingers. Bernie revved the engine and sped to Elvis Presley Boulevard.

What with the lights and the shouting, Bubba couldn’t tell just how many squad cars were actually settled in the trap, cutting off their escape. They all swarmed, taking each side of the Chrysler, pulling the boys out at once. All Bubba felt were the fists raining down.

Everything seeming to move in slow-motion, but those Miranda Rights being spouted, those were in real-time. As the officer spread Bubba’s legs and laid his hands on top of the car’s hood, he watched Ronnie being taken to one car and Bruce manhandled into another.

Bubba felt himself cuffed and thrown into the backseat beside Bruce. Through the window, Bubba watched Ronnie slink down in the backseat of the other vehicle.

Some reporter—a tall, blond fellow Bubba recognized from the weekend news—was aiming his microphone into Ronnie’s window, trying to get him to speak while some police were shouting at him to back off, step away from the vehicle. A cameraman was with him, the weight of a huge video unit pulling his shoulder slightly down. The two men looked tied together by electrical wires.

Bubba let out a defeated breath. There would be no money now, he knew.

There would be no Caribbean trip or paid-off bonds and loans. Matter of fact, now there’d probably be a bunch more.

Fuck. He’d never get out of Memphis.

More reporters outside the window now, plus the cops and curious nobodies snooping around—a sea of snarls and grotesques. Bubba sucked wind back through his throbbing lungs slowly, each breath a little labored and deliberate.

While he focused on his breathing, Bubba wondered if Mike had gotten out of the cemetery all right, hoped he had hightailed it in the appliance truck and was already miles away. He hoped Mike would make it to Texas, where Mike claimed he had family and friends waiting for him with open arms.

During the ride to Shelby County lockup, Bubba also wondered something else. Something like an itch that had been itching since Ronnie had taken it upon himself to break the silence of the night, yelling through that cemetery fence.

Bubba wondered why Ronnie was taken to a different car.

Then he wondered how Ronnie had somehow landed them directly into a barricade of waiting police cars.

POLICE CLAIM FOILING ELVIS BODYSNATCHERS!

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (AP)—Police on a stakeout at Forest Hill Cemetery captured four men after a chase Monday, foiling what authorities said was a plot to steal Elvis Presley’s body and hold it for ransom.

But one of the men was freed for lack of evidence, the other three were charged with trespassing, and a police official said the plot might be hard to prove.

In a statement, Memphis police said information was received “several days ago” that a group of people was going to enter the cemetery, break into Presley’s mausoleum, steal the body and try to ransom it.

Acting on the tip, police kept the mausoleum under watch.

On Saturday night, the statement said, “suspects were seen near the cemetery … but did not attempt to enter Forest Hill.” Police were later informed, they said, “that this had been a trial run.”

The stakeout continued Sunday night, and early Monday morning, “four suspects were arrested near the cemetery after having entered over the back wall, bypassing security guards, approached the mausoleum and shook the door when they were apparently frightened off.”

Police Director E. Winslow Chapman said three of the men were arrested after a brief chase. The fourth was arrested at the emergency room in Baptist Hospital, where Presley was taken after he died on Aug. 16. Chapman said the fourth man apparently had sprained an ankle running from the cemetery.

Chapman said the police believe the men intended to use conventional burglary tools to break into the mausoleum, but he said no tools were recovered, although police searched the cemetery grounds and the route of the chase. The case against them would be weak without the tools for evidence, Chapman said.

Tuesday, August 30, 1977

Locked up again, facing felony charges of attempted grave robbery, body snatching, and trespassing.

A public defender had told Bubba in no certain terms: If it all stuck, grave-robbing would get him 99 years, but don’t worry—the botched attempt would only get him 33.

Bubba thought: in the grand scheme of things, what the fuck was the difference?

The public defender went on, “You could go up there and shoot an’ kill a guy, rather than let him testify against you, put your gun down, call the po-leece, tell 'em you just shot and killed 'em, come get 'ya, and you’ll get 30 years … Or you can let him get on that witness stand, testify against you, and you get 33 years—if they convict 'ya.”

Bubba had made the error of asking what had happened to dear old Ronnie Lee Adkins. Lawyer told him, also in no uncertain terms: Leave that Adkins fella alone.

But that wasn’t what Bubba heard. The way he saw it, the lawyer just confirmed Ronnie was worth more dead than alive.

Bruce knew where Ronnie lived, had his address written down. Having used what little money he had left to post bail—Blue Barron always won in the end—Bubba went round to Bruce, told him the new plan, to be implemented immediately.

“We’re gonna put the fear of God into Ronnie,” he’d told Bruce. “Let him think his life is on the line, he gets up on that stand and throws us all under a bus.”

They rode over in Bruce’s car, playing it cool and getting Ronnie into the front seat of the car, in the passenger’s seat for once. Bubba got in back and instructed Bruce to drive them down Poplar Avenue all the way downtown. He told him not to stop until he could see the marshes and the Mississippi River out in front.

Parked, Ronnie felt cold steel come whip around under his chin.

“You messed up real good,” Bubba hissed, pressing the tip of his butterfly knife tight against Ronnie’s Adam’s apple. He ran it slow along the scratchy grain of Ronnie’s stubble. “Real good, informing on the wrong people this time. Didn’t you?” he said.

Behind the wheel, Bruce kept a lookout for tourists. They came down here sometime to get a nice view of Mud Island. Ronnie kept his mouth tight, let Bubba keep talking. “See, you’re worth way more to me now dead than alive,” Bubba said. “Lawyer told me so. And I listen to the law, now on.”

Bruce cracked the window. Near silence where they were, the wind through the marshes and the soft lapping of the shore nearby.

“We got friends,” Bubba said, his grip on the knife and its place at Ronnie’s jugular frozen still. “And they got friends, and you know, friends of friends. Way I see it, you’re in a no-win situation. You agree?”

He loosened his grip just enough for Ronnie to slowly nod without cutting himself against the blade.

“Well, that’s good,” he said, “real good, Ronnie. So, here’s what we’re going to do: we’re going to drive you up to Baptist Memorial Hospital, drop you off, and you’re gonna tell them you’re a Memphis City policeman suffering chest pains the last few days. But you hear me? You fucking tell them you’re a cop.”

“I ain’t no cop.” Ronnie said it low, his muscles tightened against the blade.

“Don’t matter to me,” said Bubba. “Not at this point. But you’re gonna tell them that, get pinched for impersonation.”

“Why would I do that? We all already facing charges, man.”

Bubba tightened his grip again. “I want you discredited, got it? You even think about turning us out on that witness stand, I want you seen as a lying sack of shit whose word ain’t worth nothing. Your testimony won’t be no good. I already know you’re a liar—but I want it on fucking record you’re one.”

He paused, listened to the stillness surrounding the car. Seagulls hung over the river. “I mean,” he said, flicking the butterfly back into its sheath, “there’s more truth in that than anything else, right?”

ELVIS RETURNS HOME!

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (AP)—In death, Elvis Presley returned to his mansion in much the same manner as he went in life—with secrecy and tight security.

Two white hearses carried the bodies of Presley and his mother, Gladys Smith Presley, from Forest Hill Cemetery to the grounds of Graceland unannounced Sunday night.

The hearses, escorted by eight Memphis policemen and five Shelby County Sheriff’s deputies, traveled south without disruption down Elvis Presley Boulevard, three miles from the cemetery to the mansion.

The Presley family received unanimous approval from zoning officials last week for the transfer. Lawyers for the family said security and privacy were reasons for the request as well as the inconvenience caused to other families with loved ones at the cemetery by Elvis crowds.

About 100 fans watched as the hearses entered the mansion grounds from the rear entrance shortly after 7 p.m.

Tuesday, October 4, 1977

The story ran on WMC-TV on Sunday morning. It wasn’t the live feed Russ had envisioned, catching the grave robbers redhanded, but he’d still gotten the scoop Ronnie Lee Adkins promised.

Russ’ observation that the Crown Victoria closely resembled an unmarked squad car proved correct: The cops had waved them right through the Forest Hill gates. At Elvis’ mausoleum, he’d leapt out and quickly struck a pose with the mic, reporting the night’s events against the mausoleum’s marble wall. They used the car’s high-beams to light the shot. Russ then shot a clip inside Elvis’ private chamber.

Spliced together with Bernie’s footage of Raymond “Bubba” Green, Bruce Nelson, and Ronnie Lee Adkins being carted away, the completed clip aired as Sunday’s lead story. Phone calls started almost immediately, Russ’ NBC parents and the National Enquirer within the first few hours of its airing.

The Enquirer should have known better than push Russ and Bernie to hand over even a single frame to a competitive news source. But when it came to the honchos at their parent network, any footage shot with studio equipment was up for grabs. They handed over the raw footage, seeing every NBC affiliate in America use the material for their own coverage on the story.

Forget taking a bullet on Dick Clark’s blooper reel. On August 29, Russ finally reached a national audience—just as he had promised the station managers.

As he had expected, new of the attempted theft of the King’s body quickly spread, especially in Memphis. Only weeks after Elvis had been tucked and shelved in his mink-lined crypt, the botched grave robbery proved another excuse for Elvis’ wide-reaching constituency to gather en masse around both Forest Hill and the locked gates of Graceland.

Also as he expected, Russ had to cover it all for WMC-TV Memphis: the arrests, the aftermath, the eventual arraignment and, finally that October, the most unexpected twist of it all—the dismissal.

It was months later that Russ was again at Shelby County District Court, watching in disbelief as a judge announced that Green, Nelson, and Adkins were to be set free, let go, the judge declaring Adkins as too unreliable a witness to even take his word at face value.

Only Russ knew Adkins had been the tipster, the informant… the one to call him at home, for Chrissake. No one in law enforcement would say it in a courtroom, but Russ wondered if the judge been fed instructions to let Adkins walk, his clandestine status within the Memphis PD earning him some form of immunity.

Or, Russ also wondered, had someone gotten to the judge?

Russ never got the answer, but he did cover every detail of the grave robbery’s strange aftermath. The same week as the delinquent crew’s dismissal, Vernon Presley successfully circumvented the longstanding zoning codes in Shelby County, granting him permission for the legal transfer of his beloved son and wife, Gladys, back to Graceland. He wanted them home, under the shade of the trees in the backyard, right there beside Elvis’ swimming pool.

The Presley family later called it The Meditation Garden, even put up a plaque.

Later on, after Graceland later became Memphis’ greatest tourist attraction, drawing thousands of fans from around the world to take the tour, see his shag-carpeted living room and his famed white porcelain monkey, his gold Cadillac and personal jets parked outside, and his sequined jumpsuits and matching capes, all under glass next to a television set he’d used for target practice… Even then, Elvis’ grave would always remain the only part of the tour that was free of charge.

Elvis loved visitors.

Before he and Penny moved on to Denver a few years later, Russ Ruffin decided that Memphis—Elvis’ Memphis—had been good to him.

Years later, long after his Memphis days, Russ remembered something.

He had been finishing up breakfast with Penny, thumbing through that morning’s newspaper and saw an article that jogged loose memory from 1977: It was right before the dismissal at Shelby County Court.

That week in September, Russ had received another phone call at home and hadn’t thought about it in over 20 years. When it had happened, however, he had half-expected the call to be from Ronnie Lee Adkins, since another hearing was coming up.

It had been a weekday, Russ remembered, Penny out running errands when the kitchen phone rang.

“This Russ Ruffin from the TV?”

It wasn’t Ronnie, it was another voice, a new one only slightly familiar. “It sure is,” Russ said, “What can I do for you?”

There was a pause, the voice taking a deep breath before going on. “Well, you know who I am, but we ain’t ever actually spoke… Name’s Raymond Green.”

Russ had watched Bubba Green’s arraignment the previous week. Russ reached for his pad and pen. “Well, hello there, Mr. Green. Yes, I do know your name, and I’ve been covering everything about your case, as you may know.”

“I do,” he said. “Listen… Just so you know, it ain’t nothing like you heard.”

Russ didn’t say a word, let the man continue.

“You know, my story I mean,” said Bubba Green. “What you seen in the newspapers. Nothing like you heard. I got a story for you—after my hearing.”

But after the hearing, Bubba Green was gone. So was Ronnie Lee Adkins.

Russ remembered all of that, sitting in his kitchen in Denver, reading the newspaper and tearing out an article to show Penny across the table.

The story in the paper was about a former FBI informant changing his name in Witness Protection. Ronnie Tyler.

FBI WITNESS: PRESLEY CLAN STAGED GRAVE-ROBBING

Informant says pop hatched plot to move King’s plot to Graceland

(WorldNetDaily) MEMPHIS, Tenn.

August 15, 2002

An FBI informant involved in a plot to steal Elvis Presley’s body shortly after the rock idol died 25 years ago claims the Presley family staged the grave-robbing to persuade Memphis officials to move him from the public cemetery to Graceland, now a $15 million-a-year tourist attraction, a veteran FBI agent told WorldNetDaily.

The late Vernon Presley, “the King’s” father and executor of his estate at the time, wanted his son buried on mansion grounds, but it was not an area zoned for burials.

So three weeks after Elvis died of a heart attack, he had lawyers for the Presley estate petition the Memphis Shelby County Board of Adjustment for a zoning variance. They cited what they called an attempted theft of Presley’s body several days earlier and the expense of round-the-clock security.

Three men were arrested Aug. 29, 1977, near the Forest Hill Cemetery mausoleum where Elvis was entombed in a 900-pound copper coffin. One of them was Ronnie Tyler, who later became an FBI informant.

Tyler “had been in cahoots with a crooked deputy sheriff, who swooped down and ‘captured’ the thieves,” said Ivian C. Smith, former head of the FBI’s Arkansas office. “The scheme had been hatched after the Memphis board had refused the Presley family’s request to bury Elvis at Graceland,” he said.

The Memphis board on Sept. 28, 1977 OK’d Presley’s request to move his son’s body to Graceland. And the singer, dressed in a white suit with dark-blue tie and light-blue shirt, was reburied there Oct. 2.

“After the ‘theft,’ the county made an exception to the law”—and Tyler was charged with misdemeanor trespassing,” said Smith.

AUTHOR’S NOTE ON SOURCES

This article was written with the aid of Russell Ruffin, who was generous enough to offer a comprehensive interview regarding his participation in the original arrests of Ronnie Lee Adkins, Raymond Green, and Bruce Nelson.

Likewise, the Shelby County Historical Commission was patient and helpful in supplying details and fact-checking for dates and details regarding the numerous events and media coverage of Elvis Presley’s death and burial in August 1977.

Quotes and details regarding Raymond Green are courtesy of Tri-Marq Communications and WTMJ Television, Milwaukee, which provided the only existing transcripts of Green’s initial interviews.

Ronnie Lee Adkins, now Tyler, remains an active informant for the FBI, and his background information and current whereabouts do not fall under the guidelines of the Freedom of Information Act.

Other sources include:

Guralnick, Peter. Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Boston, New York, London, Little Brown and Company, 1999.

Smith, I. C. Inside: A Top G-Man Exposes Spies, Lies, and Bureaucratic Bungling Inside the FBI. Thomas Nelson Incorporated, Nashville, 2004.

Associated Press, “Elvis Returns Home,” October 4, 1977.

Associated Press, “Police Claim Foiling Elvis Bodysnatchers, September 2, 1977.

McCabe, Scott. “The Plot to Steal Elvis’ Body Gets Weirder,” The Washington Examiner, August 28, 2012.

Sperry, Paul. “FBI Witness: Presley Clan Staged Elvis Grave-Robbing,” WorldNewDaily.com, August 15, 2002.