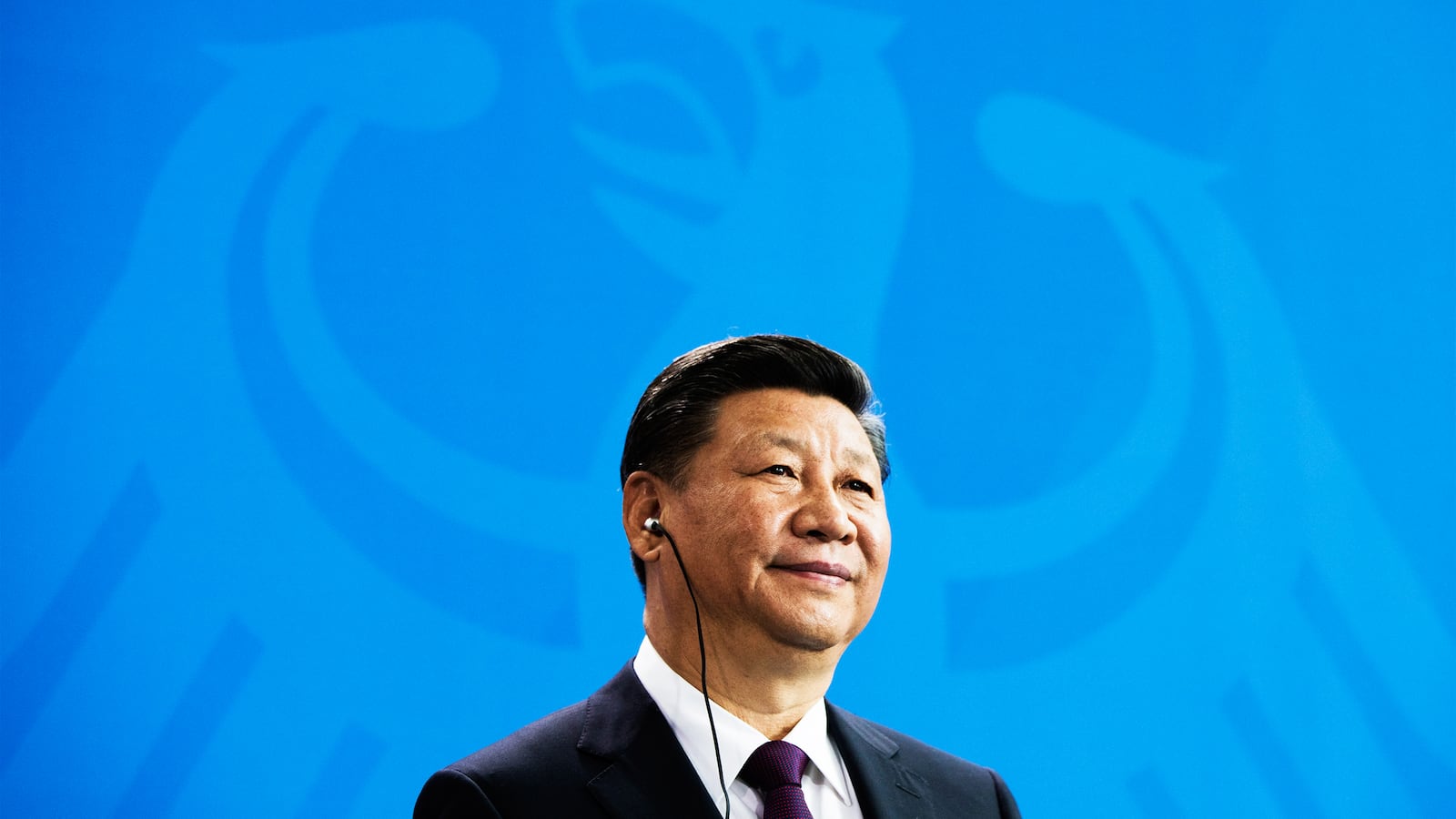

There are several recipes for going from ambitious player to dictator. Here’s one: First, become president for life, even if you don’t officially carry the title. Then, be known as a god.

Every Chinese emperor since the third century BCE has been known as a “son of heaven,” but none have claimed the mantle of bodhisattva. Chinese President Xi Jinping, however, is a trailblazer in many ways. He could be the first Chinese leader to be declared a Buddhist deity—at least, that’s the story being told by one party boss.

On Wednesday, the Communist Party Secretary in Qinghai province, Wang Guosheng, who is in Beijing for the National People’s Congress that brings together Party delegates from across the country for a rubber stamp parliament meeting, fully committed himself into the multi-day event’s pageantry. He shared that Party cadres in the northwestern province have been disseminating “images of the leader” to those being lifted out of poverty as they were given new homes. According to Wang, these “ordinary people in the herder areas” say that “only General Secretary Xi is a living bodhisattva. This is a really vivid thing to say.”

Wang is known within the Chinese Communist Party as a straight-shooter with a folksy sense of humor and the willingness to roll up his sleeves and get his hands dirty. Like Xi, he was sent to the countryside during the Mao era to live and work with peasants in rural areas. The young Wang made the best of those circumstances, and ended up becoming leader of the Communist Youth League’s local chapter. After the Great Helmsman’s death, Wang moved up steadily within the Party’s hierarchy, taking up positions across the country, until he landed in Qinghai.

The statement by Wang during the legislature gathering in Beijing comes with the suggestion that Xi must be immortalized, and that his actions—for the Party (or just his faction)—are performed out of compassion. According to Buddhist belief, it is by existing with benevolence, charity, and selflessness that a mortal can become enlightened and elevated in the ranks of buddhahood.

There is the added layer that those to whom Wang is attributing this belief—the yak herders and nomads of Qinghai—are overwhelmingly of Tibetan descent. If the claim were true, then they would be denouncing their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in Dharamsala, India, along with his administrative apparatus and 95,000 Tibetan refugees.

Wang’s proclamation of Xi’s godhood comes mere days ahead of the 59th anniversary of the Tibetan Uprising, when Tibetan guerrillas struck back in response to their land’s occupation by the People’s Liberation Army. Some claim that Mao Zedong’s troops threatened to bomb Lhasa’s Potala Palace, then the residence of a young Dalai Lama. The PLA eventually quelled the rebellion, with at least 85,000 people dead by the end of the unrest.

The Chinese Communist Party justifies its presence in Tibetan regions by saying that it has brought “development” to the plateau. During a press conference on Wednesday, Wang said that a Tibetan in an impoverished area in Qinghai grasped him tightly with gratitude during a visit ahead of Chinese New Year, and he felt that this embrace was “for the Party, for General Secretary Xi Jinping.”

And yet, those who speak up against the erasure or suppression of their traditions and culture are beat down harshly by the Party’s security apparatus, to the point where self-sacrifice may seem like the only option for them. According to Tibetan exile and Minneapolis-based labor union leader Jigme Ugen, the 162nd Tibetan self-immolation in protest of the CCP’s policies just took place.

Many of Tibetan heritage will never be allowed to set foot in their ancestral homeland. Slowly, the indigenous Tibetan presence is being removed by the Party. Last month, the South China Morning Post reported that “Dalai cliques” are now considered to be part of organized crime, with the CCP targeting even those who have abandoned the call for independence, but simply seek greater autonomy.

In the summer of 2016, Chinese officials in Sichuan province demolished a large section of Larung Gar, the largest Tibetan Buddhist learning commune in the world. The goal was to curtail its population by half to 5,000, and then build a road for tourists.

Across the country, attitudes toward China-Tibet relations are complex. The further west we go, the more likely we will see Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic group in the country, practising their belief in Tibetan Buddhism openly. And yet, attitudes toward the exile of the Dalai Lama and many Tibetans are mixed, with some loathing the spiritual leader due to his status as an alternative sort of national leader.

In 2011, then Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hong Lei said, “China’s position of opposing the Dalai Lama visiting any country with ties to China is clear and consistent.” Some have acquiesced to Chinese pressure and now shun the religious leader: South Africa has thrice rejected the Dalai Lama’s visa requests, while government officials in his host country India have been advised to abstain from attending events organized by the Dharamsala-based Central Tibetan Administration, in hopes of repairing relations with Beijing after last year’s two-month military standoff in a disputed area that involved Bhutan as well.

This week, Xi Jinping has been the cat that got the canary. With delegates taking turns praising his leadership—from practical words on his taking the lead in a “toilet revolution” to improve restroom facilities, to the gushing enthusiasm of many who say that his chairman-for-life power grab is the will of the people—this year’s National People’s Congress is very much a kiss-the-ring affair.

Come Sunday, when nearly 3,000 Chinese delegates cast their votes, Xi will be able to hold power until a successor is named, or until he is removed from office by guile or force. His dictatorship has already taken root. Proclamations of godhood may only seem like flirtations now, but just look at Mao Zedong’s legacy—he is worshipped in temples.