To anyone living in the suburban boomtown of Aurora, Colorado in the 1980s, the horror story is familiar: at some point after midnight on the night on January 16, 1984, on a quiet cul-de-sac in a newer housing development near the Aurora Mall, an intruder armed with a hammer entered the home of Bruce and Debra Bennett.

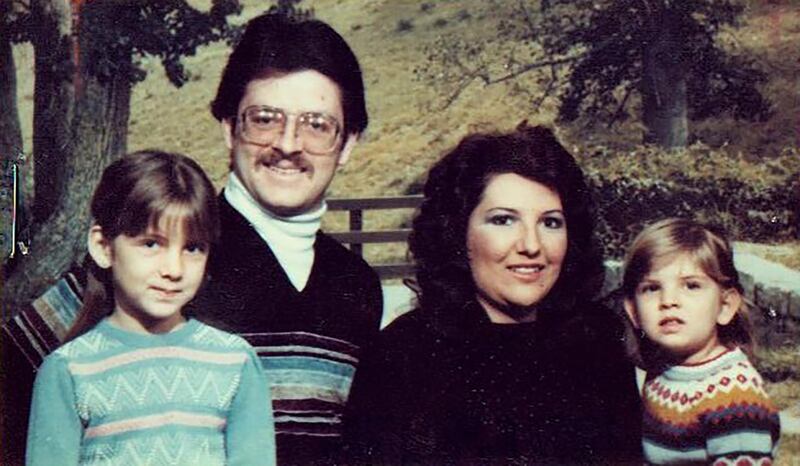

They were a young couple with two young daughters, aged 7 and 3, and they had recently moved to Aurora to raise their girls after the 27-year-old Bruce wrapped up a stint in the Navy.

As of now there’s no way to know the exact sequence of events that happened in the house that night, but the whole family was likely asleep when the intruder slipped in.

Using the hammer he brought with him and a knife he may have taken from their kitchen, the intruder attacked Bruce and Debra. Bruce fought back, grappling with the man in the bedroom and up and down the stairs, but the man overcame him, slit his throat and left him on the steps to die.

By the time the man left, he had also violently attacked and sexually assaulted both Bennett daughters.

The three older Bennetts were dead. The intruder had bludgeoned the three-year-old daughter and left her for dead as well, but according to Kirk Mitchell, who has spent years reporting on this case for the Denver Post, when her grandmother arrived the next morning, worried because Bruce hadn’t shown up for work, she found the youngster in her bed, barely alive. The littlest Bennett had survived.

For us kids living in Aurora at the time, it wasn’t enough to change the channel when we entered the room: the news of the Bennett murders made its way through our playground circles and church announcements and our parents’ closed bedroom doors.

We studied the smiling portrait of the four Bennetts published in the local papers, and they seemed like a mild and happy family. They could have been any one of our neighbors, any one of us.

We felt how cold it was outside that January, and we noticed how the crusty snow in their lawn looked just like the crusty snow in our lawns. Except for the recurrent image of a black body bag being wheeled out the front door on a gurney, their home could have been any home.

There were no signs of forced entry, we learned, no signs of motive.

We called the killer the Hammer Man, as if he was a monster or ghost, and we were fully aware that he had yet to be caught—that he was always somewhere out there.

Thirty-four years later, they may have finally found him.

I was just six months old in early 1971 when my parents moved from Los Angeles to Aurora and bought a modest, split-level home in a new development called Village East.

There were few mature trees in our new neighborhood and most lawns were flat-out dirt. From our part of town we could see Denver’s skyline and the Rockies to the west, but in every other direction the horizon held either walls of new homes or open fields of prairie grass and weeds.

Colorado was a reason unto itself for those people, like my parents, who settled in the state. Aurora is located on Denver’s eastern flank, where flat fields unroll all the way to Kansas, so it would never measure up to the sublimity of the Rockies always looming to the west, but it did hold its own allure.

Like most suburbs, it represented the best of the country (space, privacy, and relative quiet) merging with the best of the city (community, activity, and sometimes diversity). And with all of that cheap, sprawling land, homes in Aurora were affordable.

Everything in Aurora was focused on family life, from the architecture of the houses to the ways that schools and parks were neighborhood hubs, so it was no surprise that the place was lousy with kids.

I had four brothers and three sisters growing up, so our home was always teeming, but the sidewalks outside were always full of kids, as well. There was always someone to play with.

For many years of my childhood, block after block of open fields were stitched into the fabric of Aurora.

In those fields we hunted for skinks and snakes. We dug foxhole forts and carved BMX tracks in the dirt. We shot BB guns and lit things on fire, and when we were older, we huddled in the weeds to smoke banana peels and Swisher Sweets. When we went to friends’ houses, we played in their fields.

Census statistics show that during the 1970s and 1980s, the population of Aurora almost trebled, so it was inevitable that most of those open spaces would eventually become construction zones.

One day the waist-high weeds and grasses would be mowed down and raked away, taking our snakes and hideouts with them, and soon after, survey stakes would be spiked in the ground as if they’d dropped from the skies. Construction sites sprouted overnight, followed by giant holes in the dirt that would soon be smoothed with concrete and transformed into basements.

New roads and sidewalks emerged, as did street lights and street signs that looked fresh-from-the-bubble-wrap. Soon came the houses—endless houses—usually painted in shades of beige that matched the dirt around them, waiting for dogs and fences, trees and lawns and kids.

The promise of the place was underway.

The Hammer Man, we soon learned, had attacked others, as well.

Twelve nights before the assault on the Bennett family, a man armed with a hammer broke into the Aurora home of Kimberly Rice and James Haubenschild and attacked the couple as they slept. The couple survived, but Kimberly suffered a concussion and James’ skull had been fractured. They may have been the Hammer Man’s first victims.

One week before the Bennett attack, a 28-year-old Frontier Airlines flight attendant named Donna Dixon pulled into her garage, climbed out of her car, and was struck in the temple by a man with a hammer. The intruder beat her head into the wheel well until she fell unconscious, then raped her and got away. She too survived.

The next afternoon in the suburb of Lakewood, on the other side of Denver, a 50-year-old mother and grandmother named Patricia Louise Smith was bludgeoned in her townhouse—hit 17 times in the head with a hammer, according to the New York Times—while at home eating Wendy’s on a lunch break. She too was raped, and the hammer was left near her lifeless body.

Six days later the Bennett family was attacked.

Along with Aurora’s new housing developments came new malls and mini-malls and mini-mini-malls.

Everywhere we turned there were places to spend money. Movie theaters. Grocery stores. Fast-food restaurants. Car dealers. Optometrists. Shoe Shops. Bowling alleys. Pizza places. Swimming pools. Bike shops.

When a 7-11 opened up across the street from a 7-11, we thought it was hilarious.

Before long, nearly all the fields we played in had moved, one mile at a time, to the edges of the prairie. If there was a sense of loss attached to these missing blocks of land, it was short-lived, cured by the arrival of the malls.

Despite the ashtrays standing next to every bench and planter, the malls were clean and thriving, spread all over metro Denver, and they bore regal, optimistic names like Cinderella City and Villa Italia.

Buckingham Square was right down the road from my house, and it had foamy fountains and indoor water slides, a game arcade and all-you-could-eat nachos, record stores and a magic shop. It’s hard to imagine now, but according to Dead Malls, in the early 70s, over 150,000 people visited the Buckingham mall during an average week.

Malls during those decades were embodiments of comfort and possibility, and like schools and parks and churches, acted as community centers for young and old alike. Their ubiquitous presence added self-sufficiency and even luxury to the suburban appeal: everything we could ever want or need was within reach. We were enchanted and distracted.

But Aurora, like all suburbs, had a darker side as well, the rats within the walls. We didn’t have to look far in pop culture to see suburban life being skewered for its defects and sins: racial and cultural homogeneity; gender bias and misogyny; alienation and isolation; demonization of the urban and the Other; wastefulness and conspicuous consumption.

As kids, we may not have recognized all of these cracks in the veneer, but we knew that Aurora was far from Walnut Grove. Bad things happened there as they did everywhere.

The boy-next-door’s father shot himself in the field across the street from our house, and someone’s parents were always getting a divorce. Under the playground swings we found baggies sprinkled with pot seeds and the occasional spent syringe, and the gift shop at the mall sold cocaine spoons and books of racist jokes.

Many parents beat their kids and my grade school buddy died of an asthma attack. A group of us boys would sometimes dumpster dive through apartment complexes to collect aluminum cans to turn in for coins, and the quantity of porn we found was astounding.

People drank. People smoked. People fought. People died.

But not like that. No one was supposed to die like that.

Nothing had prepared us for the Hammer Man.

Because of his weapon of choice, and because of the number of housing and shopping developments under construction in the vicinity of Alameda, where the attacks occurred, some locals believed that the Hammer Man must have been a construction worker, maybe someone who’d come to Denver for temporary work.

Despite its scapegoat flavor—hostility toward non-“natives” being a pastime in Colorado—for those of us living there in the '80s, that possibility made as much sense as any other.

After the attack on the Bennetts, the Hammer Man stopped his spree, at least in Colorado, but it was too late. Aurora had been transformed.

People’s reactions to the Hammer Man were largely what you might expect. Over the decades, many police officials expressed the kind of honest shock that elicited great faith in their humanity, but also left an aftertaste of worry, as if they too were bewildered by the enormity of such evil, and frustrated by their inability to bring the killer to justice.

A police rendering for the Bennet family’s killer

Aurora Police DepartmentAt a recent joint press conference held by the Aurora Police Department, Chief Nick Metz stated that it “was obvious that this case haunted our detectives and officers who responded that night. This was a case that… shocked the conscience of our community.”

One 1994 report published in the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News cited a detective who, ten years after the murders, continued to have a photograph of the Bennett girls on his desk.

One common theme was the way that the crime, for a lot of us, redefined Aurora overnight, turned it into a terrifying place. A family friend told me she never worried about locking her doors before the Hammer Man, and never left them unlocked after.

Guns and home security systems were on every family’s mind. All over town, in the middle of the night, kids held their pee rather than dash down the hall to the bathroom.

One of my sisters convinced herself that if she covered her head with blankets as she slept, she’d be protected from the Hammer Man’s blows.

My dad, who is now 83 and still lives in my childhood home, thought first about protecting his wife and eight kids.

“I had a hammer, too,” he said, implying that he would have used it if any intruder ever endangered our family. Hearing him say that, it’s hard not to imagine Bruce Bennett fighting back in the middle of the night, feeling that same furious desire to protect his wife and kids.

Even decades later, my mom had tears in her eyes when she told me that she never looked at a hammer again without thinking of that poor family, of that little girl who, by the grace of God, made it out with her life.

More than anything, people talked about this little survivor. All of us knew her name: the three-year-old girl in the newspaper who had to have her skull reconstructed, her jaw wired shut, and who had pieces of bone in her windpipe.

She taught us more than we’d ever understand about abject violence, including the fact that it can divide your world into the before and after, and that it can take everything away.

I was 13 years old that year, smack in the middle of eighth grade, watching too much television and hiding the fact that I needed glasses.

Like a lot of locals, in the months after the Hammer Man I’d never been more scared in my life. I’d spent a lot of time in the Bennetts’ neighborhood, at friends’ houses and at the new Aurora Library and the old Aurora Mall, so there was a horrible familiarity to the murders, and an inescapable sense that the Hammer Man was always nearby.

We had so many kids coming and going from our home that our doors and windows were rarely locked, and our dog—a dreadlocked Old English Sheepdog named Wilbur—got so used to the constant traffic that he’d barely roll over from his lump atop the stairs when people barged in without knocking. My family and I were inevitably next.

The bedroom I shared with my brothers was still covered with the choo-choo train wallpaper that we’d all outgrown years before, and by 1984, when the murders happened, it had begun to peel away, and the drywall behind it was pitted with holes from wrestling matches and tantrums that had gotten out of hand.

Though I often fantasized about having my own bedroom someday, during those months it was comforting to sleep in a crowded room, in a crowded house.

I would sometimes wake up in the dead of the night and stare with terror at our open bedroom doorway, just waiting for the Hammer Man to materialize in the dark, just as he had at the Bennetts'. The most comforting sound in the world was the snoring of my brothers.

Around that time, my friends and I had begun to sneak out in the middle of the night to roam the neighborhood, hiding from curfew-minded cops and leaving clueless acts of cruelty wherever we went. But when the Hammer Man appeared, all of that came to a halt.

Because he was nowhere, he was everywhere. He seemed emblematic of all the evil in the world, of all horrors beyond our control. He represented a terrible new reality, one that most of us couldn’t—and didn’t want to—fathom.

It seems fitting that that was the year I’d become obsessed with Mr. T. By then I’d moved to the lower bunk and gained some wall space, right next to my head, where I could plaster the photos of him that I’d cut out of TV Guide and Parade magazines: little disembodied Mr. T heads; Mr. T wearing overalls; Mr. T, hands on hips, scowling above his ropes of gold. On The A-Team Mr. T played B.A. Baracus, initials that we told ourselves stood for Bad Ass, but in reality stood for Bad Attitude, or Bosco Albert, depending on the episode.

That year also marked the peak of the Mr. T cartoon, and the release of a made-for-TV movie starring Mr. T called The Toughest Man in the World.

That title said it all.

The Hammer Man terrified me, but over time the shock of his violence faded away, as it usually does. I didn’t begin scrapbooking articles on him, nor did I set up a bulletin board with photos of his victims pinned to a map.

I may have chronicled his attacks around teenage campfires and college dorm rooms, but by then he had largely become another ghost story or myth, up there with the Feral Albino who haunted the prairie beyond Tower Road.

I never realized how deeply entrenched my fear of him was until 2006, more than two decades after that January night, when he made his way back into my life in a different way.

I’d moved away from Colorado by then, had traveled a lot and lived on both coasts, and ended up living in a small town in rural Washington with two young kids of my own.

For a number of years I’d been writing fiction, and I found myself starting the early stages of a mystery novel about a woman named Lydia who worked at the Bright Ideas Bookstore in Denver (a thinly veiled Tattered Cover, where my wife and I had worked for years).

I wanted Lydia to have survived some kind of traumatic childhood incident that was intruding into her adult life, interrupting the book-lined sanctuary she’d found in the store, and in the early months of the writing process, I kept coming back to an image of her as a 10-year-old girl, sleeping at a friend’s house, hiding under the kitchen sink as the Hammer Man prowled the house.

He was a looming silhouette, an inky cloud of unfathomable evil, holding a dripping hammer. At the time, it felt as if he had appeared on the page without my consent.

In retrospect it seems inevitable that the Hammer Man had taken root in my imagination as a stand-in for the worst acts that humanity has to offer.

Rather than attempting to recreate or shed light on the real-life murders, fictionalizing him in Lydia’s world became for me a way of exploring the emotional ripples of violent crime, especially the idea that violence can not only derail the lives of those immediately affected, but create a shockwave that echoes out forever.

Dropping the Hammer Man into a fictional world allowed me to work through some of my oldest fears, and try to give closure to horrors that, for decades, had remained unsolved. By the end of the writing process, my imagination had steered me into an alternative universe in which the Hammer Man could be controlled, contained, and maybe even caught.

I had no idea that this would ever become a reality.

Over the decades, the Aurora Police Department has remained persistent in their desire to catch the Hammer Man. After the murders, Mitchell reported, over 500 people were interviewed in the investigation, but none of them led to an arrest.

In 2002, the Aurora Police Department issued a rare “John Doe” warrant for the Hammer Man, which basically meant that the DNA evidence was strong enough to single out an unknown individual and charge him with a long list of crimes.

In 2010, using DNA traces found in semen at two of the crime scenes, Aurora Police detectives definitively connected the murder of the Bennetts to the murder of Patricia Smith—but, again, the DNA wasn’t traced to any individual on record.

And then two years ago, in 2016, the Aurora Police Department released a composite sketch of the Hammer Man’s face based on the DNA he left behind—what he might have looked like as a young man and as an older man, according to his genetic traits. The hope, of course, was that the image might refresh an otherwise cold investigation.

For many people, including myself, seeing a DNA approximation of the Hammer Man’s face revealed something that’s always been difficult to imagine: the Hammer Man as a living, breathing human being.

Not a devil or a monster, but a man.

In a 2017 email, Steve Conner, a detective in the Aurora Police Department’s Cold Case Squad, noted that it was “odd” that investigators hadn’t found any connections between the Hammer Man attacks and other crimes nationwide. “A spree killer,” he said, “doesn’t just bloom one day and perish the next.”

His reading of the killer now seems prescient.

One afternoon in early August, 2018, my phone began to erupt with messages from friends and family, co-workers and classmates, all of them living in Denver. Each said the same thing:

They got him.

They got him.

They got him!

That remains to be seen, though for as long as he’s worked the Hammer Man case, Detective Conner has always held hope that “ever evolving technologies” would eventually lead to a breakthrough. After 34 years, that may have finally happened.

Each night, the Colorado Bureau of Investigation runs a comparison against the Combined DNA Index System database (CODIS), run by the FBI, which collects and indexes DNA from different states and agencies.

In early July of this year, the agency got a hit: a match was found between the DNA of the wanted John Doe suspect—the unknown man whose semen was traced to both the Bennett and the Smith crime scenes—and that of a 57-year-old prisoner in Nevada whose cheek was swabbed in 2013 as part of a new state law, his data uploaded.

The man, Alexander C. Ewing, was serving a 40-year sentence for two counts of attempted murder and other crimes and was eligible for parole in three years. According to a Washington Post report, he lived in Denver in 1984—and worked in construction.

Not long after the Hammer Man attacks had come to a halt in Colorado, Ewing was arrested after breaking into a home in Kingman, Arizona and beating a man’s head with a massive granite rock.

On a gas station stop while being transported to prison for that offense, Ewing escaped and made his way to Henderson, Nevada. There, in August of 1984, nine months after the attacks in Colorado, Ewing broke into a home and attacked a sleeping couple with an axe handle as their boys slept in other rooms. The wife managed to call 911 during the attack, and the couple survived.

Ewing was arrested near Lake Mead a few days later, and he has been in prison in Nevada ever since.

According to the New York Times, when told about the DNA match to the Hammer Man crimes, Ewing said, “There’s got to be a mistake.”

Extradition processes began immediately. There will be a trial in Colorado, where a complex case will be made more complex by the passage of 34 years. For obvious reasons, law enforcement officials in the state have been emphatic in their assertion that Ewing is innocent until proven guilty. This is potentially a death penalty case.

Formal charges against Ewing in the Smith case came last week, and formal charges against him in the Bennett case are expected soon.

“Justice in this case has been delayed,” District Attorney Peter Weir said during the August 10 press conference, “but I’m confident that justice is not going to be denied.”

Every place has its scars—they tell us who we are—and Aurora is no different.

Maybe every child in the contemporary world has a moment when they realize that monsters are real. It’s the moment of their 9/11. Their Chuck E. Cheese shooting, their Columbine, their Aurora Theater massacre.

We are changed forever by these bursts of abject violence, and the places where these bursts overlap with our nostalgia are fundamentally changed as well.

And yet: it’s no coincidence that the word "Aurora," in Latin, means "Dawn," a fitting translation for a place that has always represented new beginnings, where people have always looked forward rather than back.

I haven’t lived in Aurora in three decades, but my dad still lives in my childhood home and I visit often. Over time, all of my neighborhood friends have dispersed, replaced—quite literally—by people from all over the world.

According to the Denver Post, nearly 20% of Aurora’s residents today were born in other countries. The playgrounds and schools there have become microcosms of the globe, with students representing 130 nations and speaking 160 different languages.

An East African restaurant that’s down the street from my dad’s house shares a parking lot with a Denny’s, and there are Asian markets nearby that rival the size of a Costco.

Aurora has become a thriving cosmopolis, or at least a suburban version of one, and although there’s a tendency for some to see Aurora as utterly transformed from what it was, in the most important ways it is exactly the same.

People settling in Aurora today are looking for the same thing my parents were looking for when they bought a home there in 1971, and the same thing that Bruce and Debra Bennett were seeking a decade later, before their lives were taken from them: a safe, affordable place to live and work, to raise kids and be a family.

The Hammer Man’s arrival in 1984 was so disruptive to me and so many others because, deluded or not, we had all counted on this very promise: safety, comfort, possibility.

That promise is still alive in Aurora, and if it holds true that, after 34 years, they finally caught the Hammer Man, one tragic chapter in the city’s history can finally begin to close.

UPDATE: A jury found Ewing guilty of the murders of the Bennett family on August 6, 2021.