Nativism is on the rise in the United States, as the tragic events at Charlottesville and this week’s feints to revoke DACA protections put on display. Racism and bigotry have been given appalling cover and encouragement by an administration that has also trafficked in anti-immigrant rhetoric and demagoguery.

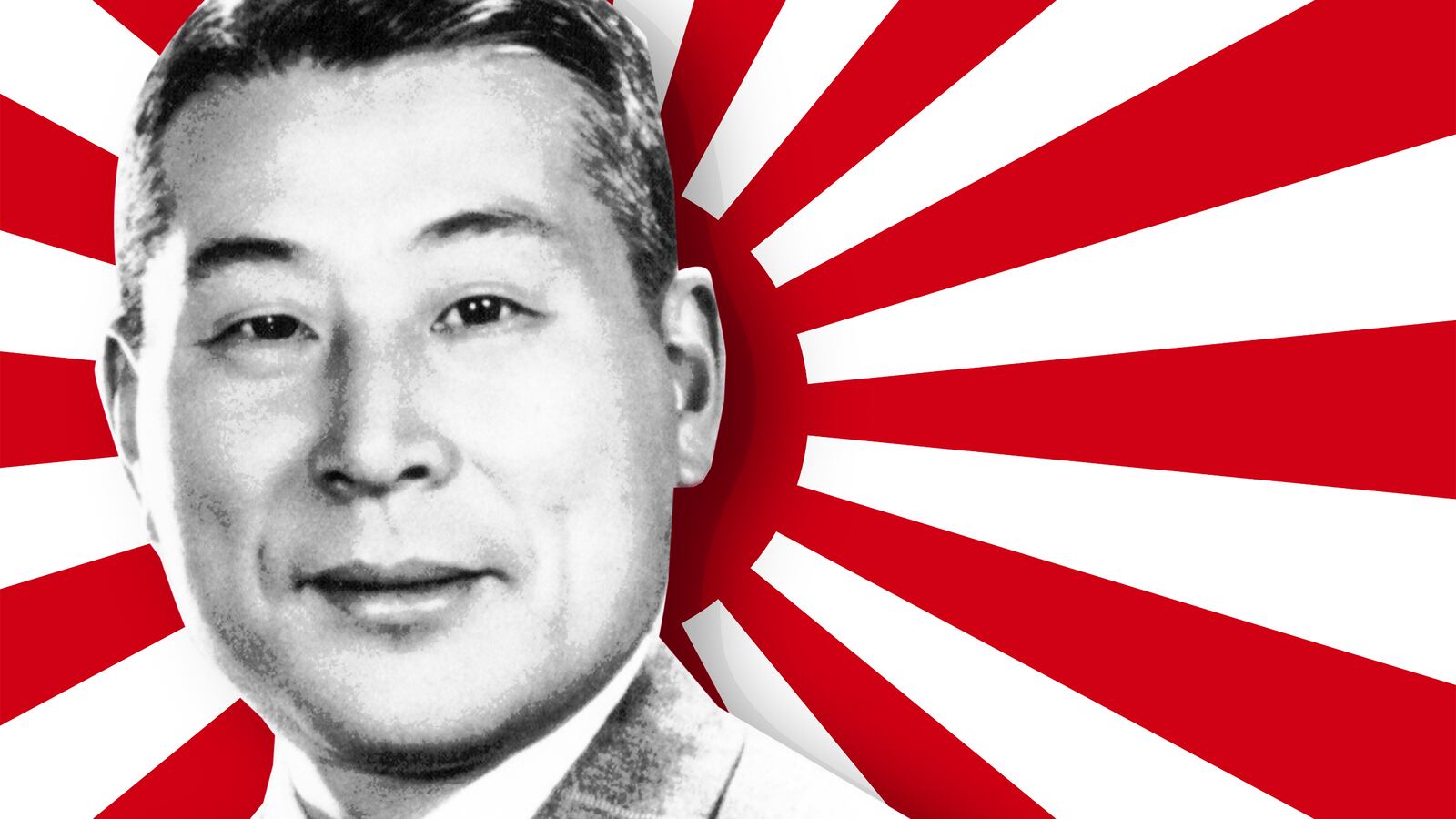

How timely, then, to recall the selfless and heroic actions 77 years ago this month of a Japanese diplomat, who, thousands of miles from home on the front lines of the Second World War, risked his own life and career to save thousands of innocents fleeing from the Nazis. The little-known story of Chiune Sugihara is an inspiration to all people of goodwill.

Born into a middle-class family on the first day of the 20th century, Sugihara recalled in his memoirs intentionally failing his medical-school exams, to his physician father’s disappointment, to pursue his interest in European languages. He studied to be a Sovietologist and was a senior official in the foreign ministry of the puppet Manchurian state of Manchukuo, spending 16 years in Harbin, where local émigrés further improved his Russian. In November 1939, Sugihara took up the post of vice consul in the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, just two months after the German invasion of Poland had started World War II.

Japan had not yet joined the Axis and one of Sugihara’s primary tasks was to gather intelligence on Russian and German troop movements in the Baltics. In this capacity, he made contacts with the Polish underground and issued some transit visas in June 1940 to those fleeing the Germans. At about the same time, Jan Zwartendjik, the manager of a local Philips plant and acting consul of the Netherlands’ government-in-exile, was approached by a group of Dutch Jews living in Latvia seeking visas to the Dutch West Indies. His boss, Ambassador P.J.L. de Dekker, gave the green light and even signed some of the papers himself. Soon Polish and Lithuanian Jews fleeing the Nazis also approached the consul for help and Zwartendjik bravely issued them more than 2,000 visas for the island of Curaçao in the Caribbean. But even with the Dutch papers, refugees could not escape through the Soviet Union without a separate transit visa. This was, however, a document that the Empire of Japan could offer.

Aware that Sugihara had helped the Polish underground, desperate refugees began crowding the courtyard of the Japanese consulate pleading for help. For Sugihara, the moral imperative was obvious. “They were human beings and needed help,” he declared. After three times requesting instructions from Tokyo and receiving little guidance—beyond an order that only refugees with proper funds and pristine papers be granted passage—Sugihara sprang into action.

He took a real risk in doing so. He was acting against the instructions of his superiors and in direct opposition to the invading Germans. “I may have to disobey my government, but if I don’t I would be disobeying God,” he told interviewers decades later.

Over six weeks, Sugihara issued 2,139 transit visas, asking nothing in return. Two terrified teenage girls later recalled the “gentle-looking man” who saved their lives. He further arranged for Soviet officials to allow transit for many of the refugees on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok on the USSR’s Pacific coast. At the other end, Tatsuo Osako, a tourist bureau employee, escorted those fleeing from Russia to Japan and then onward.

Sugihara wrote the visas by hand, sometimes working 18 to 20 hours a day and with help from his wife, until the day in early September 1940 when the consulate closed. Witnesses recalled him continuing to write visas on the way to the train station, eventually even signing blank papers and throwing his seal into the crowd. Bowing deeply from the train, he was heard to say: “Please forgive me, I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

Huntington Beach resident Hanni Vogelweid (maiden name Zongejmer) and family were saved from Holocaust by Chiune Sugihara, left, a Japanese diplomat who issued thousands of visas to Jews in Lithuania. The name list is photo of document showing Jews officially granted those visas. Below3 passports of family members that Hanni kept. Left is passport cover. 'J' at top was stamped on 1st page of all passports of Jewish people. Below right is page stamped by Japanese.

Alex Garcia/Los Angeles Times/Getty ImagesSugihara was relocated to Berlin, where he wrote 69 additional visas in the shadow of Hitler’s Reichschancellery. He then worked as consul general in Prague before moving to Bucharest for the remainder of the war.

After the Allied victory, he was imprisoned for 18 months in a POW camp. Upon his return to Japan, he was asked to resign from the diplomatic corps, largely due to his unauthorized actions saving refugees, and eventually was forced to work a series of menial jobs to support his family, including selling light bulbs door to door.

Although some of Sugihara’s visas were sadly unable to be used, estimates put the number of Jewish refugees saved at in excess of 10,000 souls, including many children. Today descendants who owe their life to Sugihara and his friends are estimated to number more than 40,000. In 1984, Israel’s Yad Vashem conferred the title of “Righteous Among Nations” on him in a ceremony in Jerusalem. Sugihara died in 1986.

At a time when xenophobia, racism, and anti-Semitism are openly entering the political mainstream in America, the story of a man who risked his life and career for refugees with whom he had no national or personal tie (there were indeed almost no Jews in Japan at all) is an object lesson. Sugihara told interviewers he was merely responding to “the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face to face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them.”

Let us hope that his example might inspire such sentiments in our citizenry.