Last year the library in the town where I grew up unveiled a $20.8 million transformation project. Among the new features: a museum-quality store, an 18-foot video wall, two professional multimedia studios, an outdoor deck, an enhanced MakerSpace, and a Yamaha Disklavier piano. There were also water bottle refilling stations, extended café hours, double the number of entrances, and fewer books.

Was it true, as the bookish gossiped, that nearly a third of the library’s physical collection had been discarded? No official number was forthcoming. All we knew for certain was that the main floor, previously the home of the stacks, had become “flex space,” and the majority of the adult books were in tight quarters on the ground floor. Moreover, thanks to zealous weeding, some titles came and went so fast in the catalog that it was almost as if books were on loan to the library.

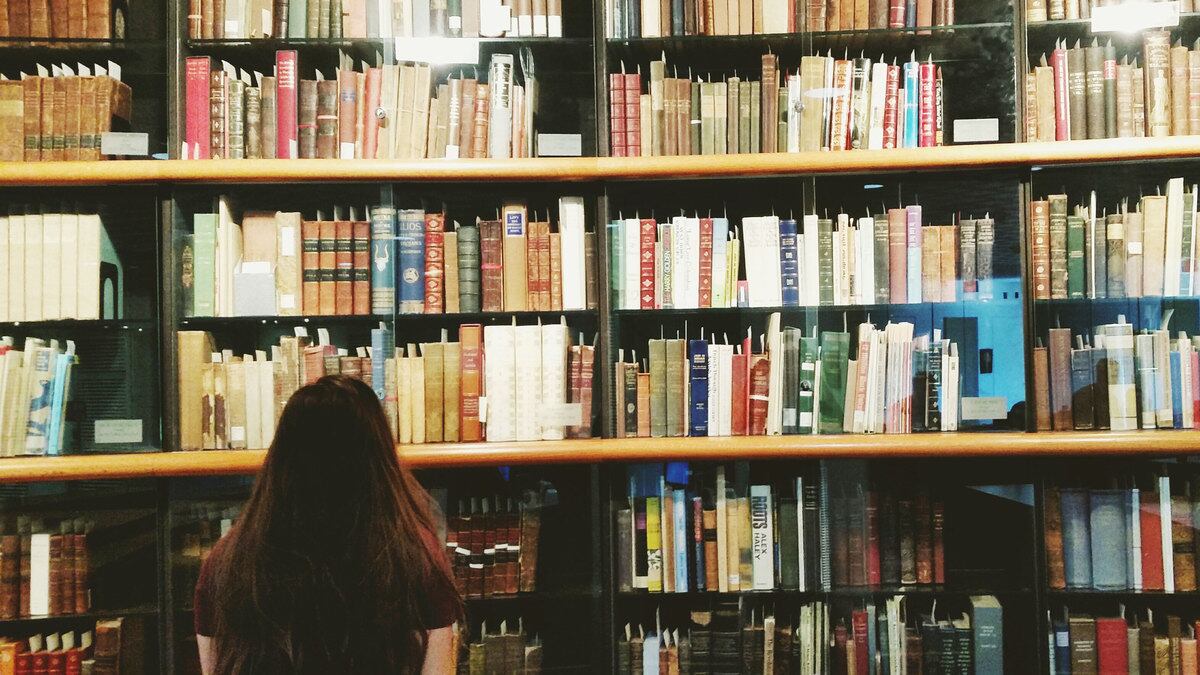

And yet the bookish did not boycott the place. It was there, in fact, that I heard their grumbles about the reduced collection. Whenever I was in town to see my parents, I myself went to the library, and if it did not always have what I was looking for, it could be counted on to supply something oddly better: that which I didn’t know I wanted. Sometimes I left the building with one pleasingly subversive sentence (Michael Gorra, from his foreword to The Daily Henry James: “[N]o scholar has ever paid it much attention, and for decades it survived in the only way that forgotten books do survive: undisturbed in the stacks”). More often, it was with a sense of a freshened-up self and world. Why had I never heard of X? How had I lived so long without Y? In the stacks, William H. Gass writes, “such epiphanies, such enrichments of mind and changes of heart, are the stuff of every day.” Which must be the reason that in final hours before the March shutdown, I visited my hometown library twice.

Then I returned to the city where I now live, and where the two libraries I frequent—one public, the other serving the college where I work—were also closed. Though I’ve seldom gone a week of my literate life without the library, I thought I’d be fine. After all, I have a makeshift home office, a regifted Kindle (never mind that I hadn’t used it), access to wondrous databases, and, on my better days, a sure grasp of the word “non-essential.” During the first weeks of sheltering in place, I even forced myself to ask whether I’d exaggerated the sense of possibility I associate with the stacks. My libraries aren’t exactly the Bodleian, and I am deeply familiar with huge portions of their collections. Really, how many miracles could still be in store?

Throughout the spring I did my usual amount of reading, which yielded the usual number of leads—books I planned to borrow when the library reopened. I soon realized that no, I did not want them on a screen (my screen fatigue had reached the point where once, watching a video, I wished it were available as a book). And grateful as I was for curbside pick-up when it came along, I also realized that nothing would ever beat retrieving books myself. Shelf-shopping was what I longed for; I missed the sparks it set off in me, the accidents that happen only when you go from 027.4799 to 944.025 in under ten seconds.

Almost a decade ago a state-wide library conference was held in my city. At a café I met an attendee who provided me with statistics as memorable as her name, which was Starr LaTronica. Some studies have found that two-thirds of circulated materials are discovered serendipitously; others put the figure at 85 percent. I thought of those numbers whenever I reflected on how much my mind had been deprived of during the pandemic. This, of course, was why the library never grew stale: Though the collection didn’t change all that much from day to day, I did—thanks in large part to what I stumbled on there. Never quite the person I’d been before the book I’d most recently read, I was reliably game for something that had previously held scant interest.

One would think that the glories of serendipity had already been established by writers and scholars, no small number of whom seem to have preferred the library to school. (“I was made for the library, not the classroom,” Ta-Nehisi Coates recalls. “The classroom was a jail of other people’s interests. The library was open, unending, free.”) But if a reminder was needed, students at Yale provided one last year, along with some evidence that the stacks aren’t just for old people. The Washington Post reported that when the university announced plans to reduce the main undergraduate library’s print holdings from 150,000 to 40,000 to make space for additional seating, “Nearly 1,000 students signed up on social media to participate in a ‘browse-in,’ vowing to check out everything from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to Dr. Seuss’s The Sneetches to show university administrators that young people still value the printed word.”

It’s unfortunate, then, that libraries making a case for their continued relevance tend to play up everything but the magic of the stacks. A few years ago, I served on the search committee for my college’s chief librarian. We received scores of impressive applications and hired someone superb, but not a single cover letter brought up the importance of browsing. A colleague to whom I mentioned this, someone who had presumably benefited as much as I from roaming privileges, responded with a shrug. “Here’s my question,” she said. “Do we even need a library?”

Having existed for the better part of a year without full access to mine, I know that I do—surely not as much as those who come for computer guidance, language lessons, the internet, or peace; more, I’m betting, than those drawn by bean bag chairs, quinoa tabbouleh, and library-themed onesies. No matter what lures us to the library, though, as long as there are stacks, we may wander into them and never be the same. As they try to reopen or stay open, let struggling institutions not lose sight of this fact, nor five-star libraries make light of it.

In his book More Lives Than One, the naturalist Joseph Wood Krutch relates the story of a boy whose intellectual life began in the unremarkable library of a tiny Iowa town. The boy had the privilege of the stacks, and by chance he pulled down a novel and read the first sentence: “All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Asked if it was a good book, the librarian, who could have declared it too old for the boy, replied, “Well—it’s a very strong book.” Krutch noted that “[t]he second most important thing about the little Iowa library was a wise librarian. But the most important thing was the fact that the book was there. That library would have been justified by its fruit even though no one else had ever read its copy of Anna Karenina.”

As it happened, the boy became a historian who wrote several books. I’d treasure that library if he had merely gone on reading them.