Hannibal Lecter came to broad public attention with The Silence of the Lambs, both the 1988 novel and the 1991 film, but Thomas Harris had been refining Hannibal ever since he first appeared in his novel Red Dragon in 1981, and he continued to fill in his backstory through another two novels, giving him aristocratic Lithuanian and Italian heritage and a traumatized childhood. His parents, we learn in Hannibal Rising (2006), were killed by a Nazi bomber, his sister murdered and eaten by Nazi collaborators right before his eyes. Unbeknownst to himself at the time, Lecter is fed his sister’s remains.

Broadly speaking, Lecter was apparently inspired by a well-born Mexican doctor, Alfredo Ballí Treviño, who murdered his friend and lover and mutilated his body and later is thought to have killed and dismembered an unknown number of hitchhikers in the late 1950s and early ’60s. (I’ll say it again: Don’t hitchhike!) Out of that seed eventually grew, in Thomas Harris’ mind, a genius-monster who turned his victims into gourmet meals and played nonstop mind games with anyone who tried to engage him. To be sure, Lecter is a brilliant creation, but if we had Harris’ rich imagination and literary skills and an actor of Anthony Hopkins’ talent to bring him to life, any one of us with the Behavioral Science Unit (BSU) could have come up with something similar.

Hannibal Lecters were our daily diet (no pun intended). We saw echoes of him constantly—through in-person interviews we conducted, by studying their victims’ remains, and by poring over case studies of earlier serial killers to hone our understanding. Most of us had seen our own Hannibal Lecter face-to-face in one form or another, often in unforgettable circumstances.

Anthony Hopkins, The Silence of the Lambs, 1991

AlamyOnce, John Douglas and another agent, Bob Ressler, were interviewing Edmund Kemper at one of the prisons for the criminally insane where he is still spending the rest of his life when, by accident, all three of them got into the same elevator during a lunch break. In the interview room, correctional guards were right outside the door, looking in. Now John, who was a little over six feet, and Bob, who was shorter, were in an enclosed container with a ruthless 6-foot-9 serial killer.

This is how John described the moment to me:

“‘You know,’ Kemper said to us, in his almost robotic voice, ‘I could kill you both right now if I wanted to.’ And we both knew he probably could do just that and not feel a moment’s guilt or remorse about doing so.”

It was, John would later tell me, the longest elevator ride of his life, but Kemper, I’m certain, enjoyed it immensely.

This was after the book and movie versions of The Silence of the Lambs had appeared. Kemper would have at least read the former if not seen the latter. It’s not inconceivable that he was consciously channeling his inner Hannibal at that moment, but by then Edmund Kemper had been evil incarnate for decades—real evil, not the fictional version; our very own evil at BSU.

Maybe inevitably, since I had something to do with how she was portrayed on-screen, however, Clarice Starling remains the more interesting character to me.

Patricia Kirby had been briefly with the BSU back when Harris was writing The Silence of the Lambs. The two had met then and I’m sure some of Pat can be found in the written version of Clarice. By the time the film crew came to the FBI Quantico campus several years later to shoot scenes there, I was the only female and thus naturally assigned to be the handler for Jodie Foster, who would play Clarice in the movie.

Jodie and I met regularly down in my dismal subterranean office (minus the gory photo wallpaper) and in the conference room with John Douglas to talk over just what the job was like and how the BSU worked. I also worked daily on the set with the crew and director, fine-tuning exactly how an agent might phrase something, how she would carry herself in certain situations, excising any giveaways that this was a made-for-the-big-screen version of the BSU.

One morning Jodie and I were out walking the Yellow Brick Road, as the Marine Corps base obstacle course is known, when she said to her assistant, “Get my double to do this.”

“Wait a minute,” I said, “why can’t you do this?” “I’ve never done an obstacle course.”

“Well,” I told her, “there’s a first time for everything. You’re a few years younger than I am [eight, in fact]. You look like you’re in good shape. Why don’t you do it yourself?”

So Jodie took me up on the challenge, worked with our physical trainer, Larry Bonney, and eventually ended up conquering an obstacle course that involved, among other feats, bounding over low logs, clearing an eight-foot-high steel bar, doing a wall climb, weaving through a series of high logs, clearing more high bars (two this time), then sprinting to a twenty-foot-high rope climb. The obstacle course scene is a relatively brief moment in an almost two-hour movie, but Jodie did it all herself. And to me, at least, the movie feels more real because of it.

More important to the success of the movie—and the legitimacy of Jodie’s character, at least in my estimation—were the hours I spent schooling her in just what it was like to be a woman in the male-driven and male-defined world of the FBI.

Part of that was sheer girl-talk fun. Jodie shared some tales about the famous “casting-couch” culture of Hollywood and the “industry” generally. (Think Harvey Weinstein.) I told her about my earliest days in law enforcement, at that youth training facility in Chino, California, and the slimeball guards who were forever telling me to go get ’em some coffee and about where I told ’em I would put their coffee if I got it.

The FBI was never that nakedly male piggish in my experience, but to call it an inclusive culture when I first arrived at the Tampa office in 1986 would be very, very wrong. Take clothing. I don’t think of myself as a fashionista, but I do like to dress professionally and I don’t mind making a fashion statement or two when I show up in the office. And that’s exactly what I did one day early on in my time with the Tampa office.

The black-and-white wool suit might not have been entirely appropriate for Florida weather, but I did wear it in winter. And, frankly, I thought the suit looked sharp. I had a little black-and-white polka-dot scarf for the pocket and set the whole outfit off perfectly with four-inch polka-dot high heels. Then, twenty minutes into the workday, my boss called me into his office and said I had to go home and change.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because no FBI agent dresses like that.”

“Well, of course not. Most FBI agents are men.”

“Look,” he said, “I’m not kidding. You need to go home and change—and, oh, by the way, I’m going to dock your pay for the time out of the office while you’re doing that.”

That last part, I have to admit, got my attention—and my dander up.

“With all due respect,” I told my boss, “I’m not going to do that. There’s nothing in the Manual of Administrative Procedures or in the Manual of Investigative Guidelines that addresses how I must dress. I read them carefully. They do not address polka-dot, high-heeled shoes. And, respectfully, I’m not going home and I’m not changing my shoes.”

There were eight of us on the squad, seven men and me. Two of them already knew our boss was going to send me home, and they were all snickering when I came back from my showdown.

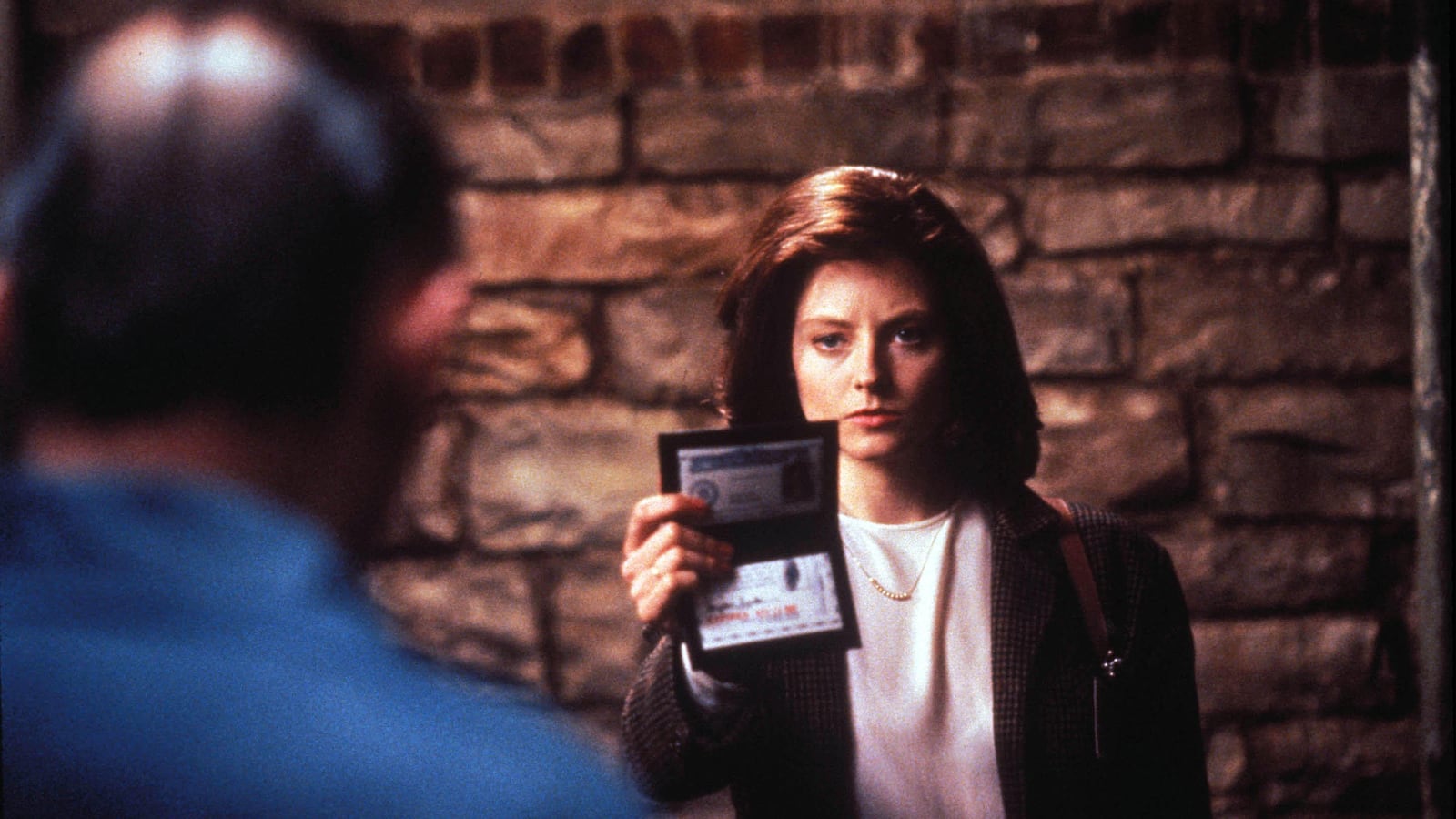

Jodie Foster, The Silence Of The Lambs, 1991

Alamy“See you later,” they said. “Hurry back, and be sure to wear sensible shoes.”

I told them I was absolutely not doing that, and only a week later two of those guys and I responded to a bank robbery in progress in time to see the robber fleeing, covered in red from the dye pack that exploded inside his sack of money. Both my partners were in their early fifties by then and not exactly fleet of foot, so I slipped off those same four-inch polka-dot heels, took off running after that bank robber, and finally caught him trying to scale a fence at the back side of a dead-end alley.

It was only when we had the felon safely behind bars at the sheriff’'s lockup that I realized I was barefoot. My partners did agree to run me back by the spot where I had shed my shoes, but they were no longer there, so I returned barefoot to the office, only to find the high heels waiting on my desk and my colleagues in high good humor about the whole incident. But no one ever bothered me about my footwear again.

Fingernails were part of the same all-male mindset. The Bureau operated on the unwritten assumption that fingernails had to be kept carefully trimmed and even created a rationale to justify the assumption: Nails that look the least bit feminine are an impediment when using firearms. Granted, I gave them some small evidence to that effect during a firing-range test when I chipped off a piece of a fingernail while trying to slam the cylinder shut on my gun and the instructor had to shut the whole test down while he helped me pry the fingernail piece loose so the cylinder would actually close. Embarrassing? Yes, of course, but I didn’t see them harassing male agents about their beer guts, and I was damned if I was going to give up the two things that define my femininity: high heels and eye-catching fingernails.

Jodie and I also had a good sisterhood laugh about another incident down in Tampa—in 1988 if I’m remembering correctly. Along with Fred Eschweiller and several other agents, I was sitting in on a very large meeting of multiple law enforcement agencies all working together on a major crime. One of the regional police captains was chairing the meeting, doling out assignments, when he happened to ask—and I’m not making this up—if anyone had brought along a “female unit.”

Female unit? I thought. What in creation is that? Then I realized that in all that big room, I alone was the “female unit,” and so, with Fred and the others choking back their laughter, I raised my hand, stood up, and said “Right here, Captain.”

“ ‘Female unit’ sounds sort of like Barbarella,” Jodie said, referring to the 1968 cult classic sci-fi film starring Jane Fonda.

“Precisely,” I replied. “Just shows what an extra Y chromosome will get you.”

It all sounds like silliness now—remnants from the dinosaur age of the American workplace—but I thought it was important background information for Jodie Foster if she was going to play on the screen the role I played every day: the lone feminine presence in what was pretty much an alpha male world—and, in the case of the BSU, a mostly underground world at that. Jodie was the consummate professional when it came to soaking it all up.

I also spent time educating Jodie Foster in the ultimate test of female survival in an alpha male world, one that involved a feral environment where all the rules of the civilized world are off: prison interviews. The basics are pretty simple: You have to know, going in, that a hundred hungry male eyes are staring at you, all at the same time, boring holes in you, tearing your clothes off with their eyes. You have to expect hooting, whistling, lewd comments, all that, and you can’t expect the guards in most prisons to do a lot to help you. I’ve known more than a few who seemed to take sadistic pleasure in the whole scene.

You’re not in danger, though it might feel that way. Those bars the guys are shouting from behind are real. But you are uncomfortable and it is awkward, and sometimes truly disgusting things do happen. By way of example, I told Jodie about the time I was walking down a prison hallway, between two rows of cells, when a guy threw something on me that I soon realized was his own ejaculate. Whether he produced it on the spur of the moment or had been holding it in his hand for who knows how long, waiting for just the right moment, I can’t say.

An almost identical scene, by the way, appears in The Silence of the Lambs, to great effect. Watching this same thing happen to Jodie’s character, Clarice Starling, was almost as repulsive as it was when it happened in real life to me, but the masturbatory prisoner and I didn’t get into a discussion about the matter because that’s cardinal rule no. 1 for this kind of work: You absolutely cannot show any emotion; you can’t reveal anger. That’s what they want, of course, and rule no. 2 is you’ve got to fight like hell as you’re going through this to keep an open mind about the person you are going to interview.

“I’m never going to interview Hannibal Lecter,” I told Jodie one afternoon, down in my BSU crypt. “There is only one Hannibal Lecter, and he’s yours to worry about. But if I’m going to interview a man—or, occasionally, a woman—in prison, odds are pretty much one hundred percent that he or she has done unspeakable things. That’s a given, but if I go into that interview room thinking this is an awful person who is likely to lie to me with every word that comes out of his mouth, I’m not going to hear and follow up on those moments when the truth is just sitting there, waiting to be spoken and explored, and if I’m not going to do that, I might as well stay home and find another line of work. You’ve got to rid yourself of prejudice and any form of preconceived notion to do your job the right way.”

I’ve always taken extensive notes about seemingly trivial items when I’ve interviewed someone—“has triple chin,” “teeth are crooked,” “sits very erect,” “slouches,” that kind of thing. Then, when I’m through and reading over the transcript, I ask myself at every key moment if I let those items color my understanding or interpretation of what was being said. I do this still, even now that I’m in the private sector and less likely to encounter serial killers in my professional life.

Most central to the compelling authenticity of The Silence of the Lambs were the further hours Jodie and I spent dissecting the critical scene where she first interviews Hannibal Lecter in prison. By then, I had done so many of those interviews—some, as I just suggested, with people only thinly removed from Hannibal Lecter—and those long hours and their many nuances and twisted contours were so deeply embedded in my psyche, that I actually found myself wanting to pour out my experience for Jodie to examine. It was a kind of purging for me as we hashed over time and again how a character like Hannibal Lecter would try to manipulate his interviewer in such a situation and how she should best react to counter him.

Honestly, too, I think we got it just right. Watching that scene in a darkened theater a year or so later, I realized I was leaning forward in my seat, gripping the chair arms, almost ready to burst into the screen if something went wrong. The public must have liked it, too, because, weirdly enough, The Silence of the Lambs was one of the best recruiting tools the FBI ever had as far as women were concerned. We had a significant spike in applications for at least two years after the movie first came out.

Only two things struck me as particularly off-key about the film. First, Clarice is still portrayed as a trainee. That’s how the novel had it, and I guess the movie had to be true to that. But a trainee would never be handed that much responsibility, or a gun, or be exposed to that much horrible risk, or expose the FBI to so much risk. They didn’t take my advice there. Second, and more dramatic, is the scene very near the end when Hannibal passes a dossier out between his cell bars to Clarice and briefly but poignantly slides his finger along hers as the handoff takes place. That’s pure Hollywood: Agents and serial killers don’t touch. But in her review of The Silence of the Lambs for Film Comment, Kathleen Murphy got the import of that moment just right: “It was an image of purest frisson, more terrifyingly intimate than any full-out assault. That whisper of flesh on flesh marked Clarice Starling as Lecter’s own.”

The filmmakers were using that moment not just to bring this movie to a close but to set up for its sequel, but I knew just what was happening in that scene—the way Hannibal kept trying to plant his malicious seeds in Clarice’s psyche. I’ve experienced that, too, from people almost as evil as Lecter himself. A few must have taken root and grown in there, because sometimes I hear them still.

Excerpted from the new book Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBI)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https:/bookshop.org/p/books/hearts-of-darkness-my-life-breaking-barriers-in-the-fbi-and-fighting-the-evil-among-us-jana-monroe/19736792?ean=9781419766114__;!!LsXw!Xo2pSOleGsnFHZ5kiOOpVd2-tggaVb5kqDXCqeig-BejsHvkwFLylAW7choCj-BsiAyEfR5GJATh66xvgDJkX8xaj_cvjw$">Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBI by Jana Monroe published by Abrams Press ©2023.