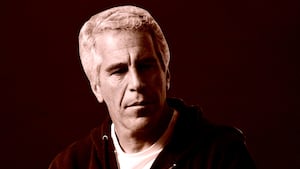

Editor's note: Jeffrey Epstein was arrested in New York on July 6, 2019, and faced federal charges of sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit sex trafficking. On August 10, 2019, he died in an apparent jailhouse suicide. For more information, see The Daily Beast's reporting here.

“Jeffrey wanted me to tell you that you looked so pretty,” the female voice said into my disbelieving ear.

It was the fall of 2002. I was pregnant, uncomfortably so, for the first time and with twins, due the following March. I was besieged by a relentless morning sickness. I was sick in street gutters, onto my desk, at dinners with friends. I suffered severe bloating and water retention.

But here was this faux-compliment coming, bizarrely and a bit grotesquely, from a woman I hadn’t met—a female assistant who worked for one Jeffrey Epstein, a mysterious Gatsby-esque financier whom I’d been assigned to write about by my then-boss Graydon Carter, the editor of Vanity Fair. (Epstein had caught the attention of the press when he had flown Bill Clinton on his jet to Africa. No one knew who he was or understood how he’d made his money.)

Upon hearing of my assignment, Epstein had invited me to an off-the-record tea at his Upper East Side house (during which I distinctly remember he rudely ate all the finger food himself) and then had his assistant call to tell me he’d thought I was pretty.

At first—it was the early stages of reporting—I was amused at having been so crassly underestimated. For a man who clearly considered himself a sophisticated ladies’ man (the only book he’d left out for me to see was a paperback by the Marquis de Sade), I thought his journalist-seduction technique was a bit like his table manners—in dire need of improvement.

If only it had all ended there. This was what it had been meant to be. A gossipy piece about a shadowy, slightly sinister but essentially harmless man who preferred track-pants to suits but somehow lived very large, had wealthy, important friends, hung out with models, and shied away from the press.

But it didn’t.

I haven’t ever wanted to go back and dwell on that dark time. But then the latest Epstein scandal broke, when Prince Andrew was accused in a Florida court filing of having sex with a 17-year-old girl while she was a “sex slave” of Epstein’s.

In the last 48 hours I’ve had a journalist from the U.K. Sun newspaper put herself inside my foyer. I’ve been inundated with requests for TV interviews. And Epstein’s old mentor, the convicted fraudster Steven Hoffenberg, recently released from jail after a 20-year sentence, has been pestering me and my agent to write a movie.

Separately, Hoffenberg’s daughter has gotten in touch—and it’s gotten me thinking. There are some injustices that maybe only time can right. And perhaps now is the time. Things happened then that simply shouldn’t have, and if I don’t talk about them, then probably no one will.

***

It became obvious as I was reporting his story that you could essentially divide Jeffrey Epstein’s biography into two themes. One was the hidden source of his wealth—he claimed he’d fueled a lifestyle of vast homes, a private jet, and endless travel by managing the money of billionaires and taking a commission, a story that no one I spoke to believed—while the second mystery was his unorthodox lifestyle.

Then in his 50s, he’d never been married but had had a string of intelligent, good-looking girlfriends, including Ghislaine Maxwell, the raven-haired daughter of the late, disgraced British newspaperman Robert Maxwell whom he promoted from girlfriend to “friend” when it was over. She remained frequently by his side.

But the New York gossip was focused on the many parties he gave at his house, where he regularly hosted a mix of plutocrats, academics from Ivy League schools, and nubile, very young women. Oh, and also Britain’s Prince Andrew, whom he introduced to everyone as just “Andy.”

I got to work on all of it—and Epstein kept close tabs on me. He didn’t want to be seen to cooperate, but he’d do his best to control me. He phoned regularly. I wasn’t altogether surprised to be quickly summoned to the offices of the rich and powerful, sometimes before I’d even asked to meet with them.

James “Jimmy” Cayne, then the cigar-chomping CEO of Bear Stearns, not only phoned me up, he found the time in his busy day to give me a tour of the office. He was on his best behavior, talking up Epstein’s alleged supposed great brain, his value to the bank—never mind the fact that Epstein had had to leave it quickly in 1981; this Cayne put down to Epstein’s ambition “outgrowing” the place.

I also met with respected real estate developer Marshall Rose; the former Bear Stearns chairman Alan “Ace” Greenberg called me; so too did Leslie Wexner, the founder and CEO of The Limited, who trusted Epstein so much he had given Epstein carte blanche to insert himself into both Wexner’s family and business affairs, according to people who saw Epstein’s contract; they all chattered on about Epstein’s brilliantly creative mind, his intellectual prowess—a mental agility that, to put it bluntly, was simply not evident in the many phone conversations he had with me.

These were conversations that took a fairly grim twist pretty quickly. “What is the nature of the piece?” he kept asking. “Does it have this aspect in it?” “This aspect” would refer variously to his philanthropy, his interest in biological mathematics, his well-known friends, some tycoons, some academic wonks—and yes, the women. “I don’t expect there’d be a piece on me without that,” he’d said, preening.

The women he directed me to were all respectable. There was a doctor, there was a socialite, there was Ghislaine Maxwell; they were all grown-ups, with the appearance of financial independence.

While Epstein’s friends speculated that retailer Les Wexner was the real source of Epstein’s wealth, Wexner (who called him “my friend Jeffrey”) never commented on this, though he did send me an email praising Epstein’s “ability to see patterns in politics and financial markets.”

My investigation began to take on unexpected twists. After a bit of digging I found myself not in some plush office setting but going through the metal detectors inside the Federal Medical Center at Devens prison in Massachusetts, where I met with one Steve Hoffenberg, a fraudster who’d been convicted of bilking investors of more than $450 million in one of the largest pre-Madoff Ponzi schemes in history. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Hoffenberg told me that he’d met Epstein shortly after Epstein had been kicked out of Bear Stearns in 1981 for “getting into trouble” and that Hoffenberg had seen charm and talent in him —“he has a way of getting under your skin”—and had hired him as a “consultant” to work with.

Hoffenberg, officially, ran Towers Financial, a collection agency that was supposed to buy debts that people owed to hospitals, banks, and phone companies, but instead the funds paid off earlier investors and subsidized his own lavish lifestyle. Hoffenberg told me had he had been Epstein’s mentor and that Epstein had made a terrible mistake in doing something so high-profile as flying Bill Clinton, since that would only draw a spotlight to his business dealings. “I always told him to stay below the radar,” he said.

Aware that I was listening to a convicted felon who had lied under oath—he was, after all, sitting before me in an orange jumpsuit—I left the jail determined to get more concrete proof about the source of Epstein’s finances. Slowly, I got there.

It took many meetings of the type you see in the movies. There I was, with my growing belly, in the backs of people’s chauffeured-driven cars, in out-of-the way hotel bars—and finally, in my sixth month, when my doctor had begun to look dismayed and told me to take it easy, a train ride to a law firm in Philadelphia, where I and a research assistant were shown a room full of boxes with legal files, and the man who brought us there whispered, “Good luck!”

Luck did shine upon me that day. I opened the first box, and there was Epstein’s deposition in a civil case explaining in his own testimony that he had indeed been guilty of a “reg d violation” while at Bear Stearns and that he’d been asked to leave the investment firm; it was the nail in the coffin I needed.

I had discovered many other concrete, irrefutable examples of strange business practices by Epstein, and while I still couldn’t tell you exactly what he did do to subsidize his lifestyle, my piece would certainly show that he was definitely not what he claimed to be.

I had to put all my findings to Epstein and, bizarrely, he seemed almost unconcerned about the financial irregularities I’d exposed. He admitted to working with and for Hoffenberg but quibbled with some of the specifics of Hoffenberg’s allegations, reminding me that Hoffenberg was a convicted felon. Third parties in turn quibbled with his accounts, and he was irritated, but not overly so.

I was a little mystified at how benignly he responded to my questions about his business activities. Now, when I look at my meticulous notes, I notice that his tempo quickened—and he was much more focused—when he himself asked: “What do you have on the girls?” He would ask the question over and over again.

What I had “on the girls” were some remarkably brave first-person accounts. Three on-the-record stories from a family: a mother and her daughters who came from Phoenix. The oldest daughter, an artist whose character was vouchsafed to me by several sources, including the artist Eric Fischl, had told me, weeping as she sat in my living room, of how Epstein had attempted to seduce both her and, separately, her younger sister, then only 16.

He’d gotten to them because of his money. He’d promised the older sister patronage of her art work; he’d promised the younger funding for a trip abroad that would give her the work experience she needed on her résumé for a place at an Ivy League university, which she desperately wanted—and would win.

The girls’ mother told me by phone that she had thought her daughters would be safe under Epstein’s roof, not least because he phoned her to reassure her, and she also knew he had Ghislaine Maxwell with him at all times.

When the girls’ mother learned that Epstein had, regardless, allegedly molested her 16-year-old daughter, she’d wanted to fight back. “At the time I wanted to go after him. I mean, physically, mentally, you know, in every way, shape, and form. And the advice I was given was, you know, he is so wealthy, he can fight you, he can make you look ridiculous, he can make your daughters look ridiculous, plus he can hurt them. And that was the thing that frightened me was that he would know where they lived and could possibly just send somebody when they walk the dog at night or something around the corner, and we’d never hear from them again,” she told me.

When I put their allegations to Epstein, he denied them and went into overdrive. He called Graydon. He also repeatedly phoned me. He said, “Just the mention of a 16-year-old girl… carries the wrong impression. I don’t see what it adds to the piece. And that makes me unhappy.”

Next, Epstein attacked both me and my sources. Letters purporting to be from the women were sent to Graydon, which the women claimed (and gave evidence to show me) were fabricated fakes. I had my own notes to disprove Epstein’s claims against me.

And then there was Epstein himself, who, I’d be told after I’d given birth, got past security at Condé Nast and went into the Vanity Fair offices. By now everyone at the magazine was completely spooked.

But my sources, my young women and their mother, heroically held firm. They were going to tell their story, consequences be damned. And as for me? My doctor insisted that once I filed this piece I lie down on my bed and not get out. One of my babies had started to grow alarmingly slowly.

***

I worked through December 2002 like a dog. I worked with three fact-checkers, the magazine’s lawyer; I sifted through everything Epstein threw at me and defused it. We were getting ready to go to press. And then the bullet came. “Graydon’s taking out the women from the piece,” Doug Stumpf, my editor, told me.

I began to cry. It was so wrong. The family had been so brave. I thought about the mother, her fear of the dark, of the harm she feared might come to her daughters. And then I thought of all the rich, powerful men in suits ready to talk about Epstein’s “great mind.”

“Why?” I asked Graydon. “He’s sensitive about the young women” was his answer. “And we still get to run most of the piece.”

Many years later I know that Graydon made the call that seemed right to him then—and though the episode still deeply rankles me I don’t blame him. He sits in different shoes from me; editors are faced with these sorts of decisions all the time, and disaster can strike if they don’t err on the side of caution.

It came down to my sources’ word against Epstein’s… and at the time Graydon believed Epstein. In my notebook I have him saying, “I believe him… I’m Canadian.”

Today, my editor at The Daily Beast emailed Graydon to ask why he had excised the women’s stories from my article. A Vanity Fair spokeswoman responded: “Epstein denied the charges at the time and since the claims were unsubstantiated and no criminal investigation had been initiated, we decided not to include them in what was a financial story.”

But this wasn’t a financial story, it was a classic Vanity Fair profile of a society figure. I don’t know—because I never asked him—if Graydon still believed Epstein when in 2007 Epstein was sentenced to jail time for soliciting underage prostitutes. But it has often struck me that if my piece had named the women, the FBI might have come after Epstein sooner and perhaps some of his victims, now, in the latest spate of allegations, allegedly either paid off or too fearful of retribution to speak up, would have been saved.

He has a way of spooking you, does Epstein. Or he did. My babies were born prematurely, dangerously so; he’d asked which hospital I was giving birth at—and I was so afraid that somehow, with all his connections to the academic and medical community, that he was coming for my little ones that I put security on them in the NICU.

When they’d been released home some months later, I went out to my first party. There was Jeffrey Epstein, sucking a lollipop. “Vicky,” he said, “you look so pretty.”

Vicky Ward was a contributing editor to Vanity Fair for 11 years. She is the best-selling author of The Devil’s Casino and most recently, The Liar’s Ball (Wiley).