Ted Bundy jerked back, appearing startled, when he first saw the electric chair inside the execution chamber at the Florida State Prison.

It was 7:02 a.m. Jan. 24, 1989.

I watched, along with 41 other witnesses, as one of America’s most notorious serial killers was strapped into the wooden chair, known by the macabre nickname of “Old Sparky.”

As final preparations for his death were made, Bundy peered through a Plexiglas window at the witnesses who faced him. “It’s all right,” he said.

At 7:05, Bundy was asked if he had any last words. He looked at his attorney, Jim Coleman, and a Methodist pastor, Fred Lawrence, sitting among the witnesses. “Jim and Fred, I’d like you to give my love to my family and friends,” Bundy said.

Then a leather strap was tightened across Bundy’s chin. A metal cap was placed on his head. His face was covered with a black, leather veil.

Prison Superintendent Tom Barton spoke briefly by phone with Gov. Bob Martinez. Barton then nodded to a black-hooded executioner standing behind a partition.

The anonymous executioner, paid $150 for the job, pushed a button.

Bundy’s head jerked as 2,000 volts hit him. His body stiffened and pressed against the chair back.

Midway through the two-minute cycle, the executioner turned off the current. Bundy’s body slumped against the leather straps.

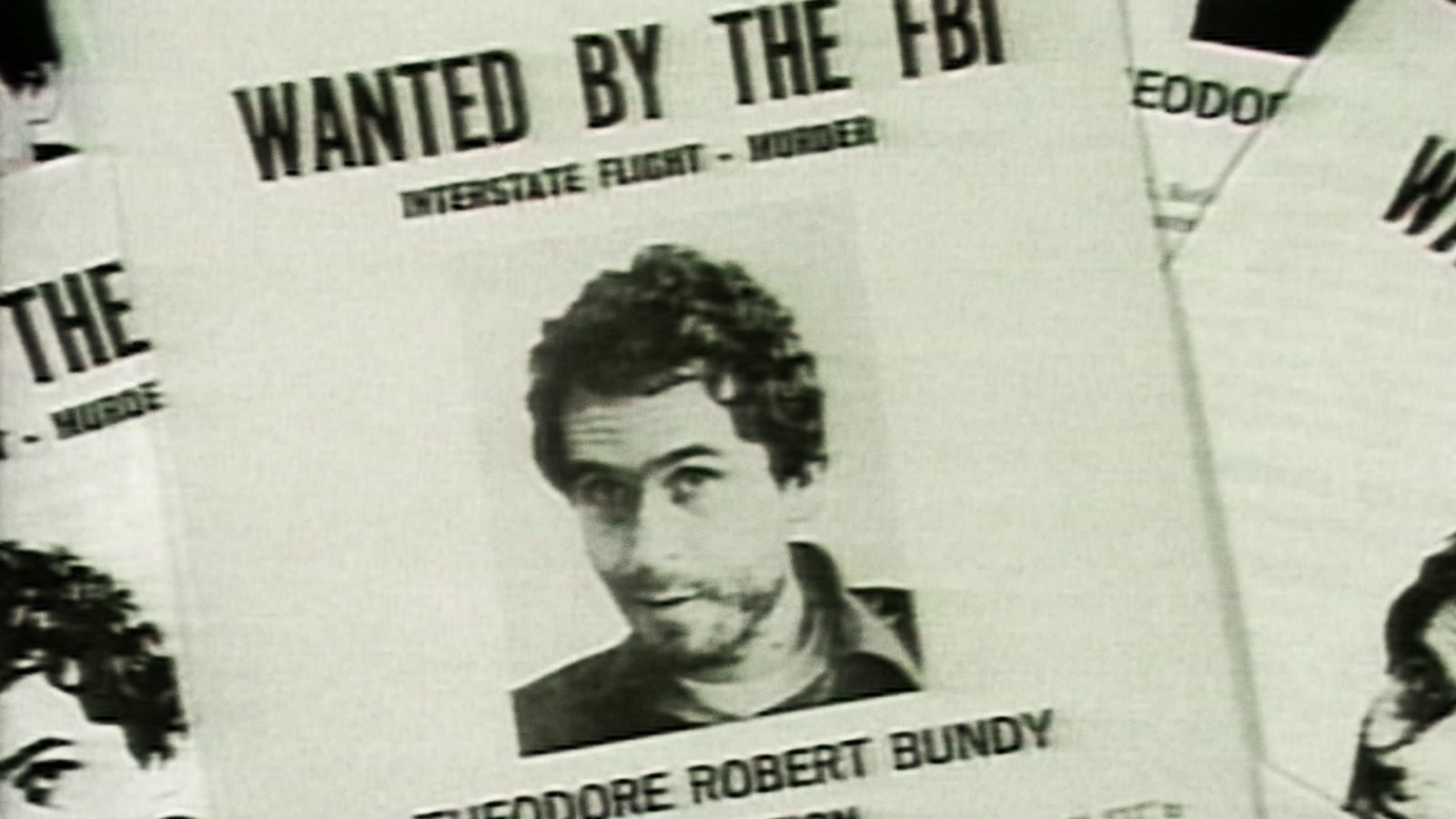

Theodore Robert Bundy—a sociopath who confessed to 30 murders, the subject of a popular TV movie, and the defendant in televised trials that captivated and repulsed millions—was dead.

Now, 30 years later, Bundy’s sick and horrific story has again caught the attention of entertainers, journalists, and the public.

On the anniversary of the execution, Netflix released a four-part documentary, Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes. The series features portions of more than 100 hours of interviews that journalists Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth recorded with Bundy on Death Row.

Zac Efron, an actor best known for his good looks, plays Bundy in Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, which won favorable reviews at last month’s Sundance Film Festival. Vanity Fair declared that Efron is “scary-good” in portraying “the killer with a charming façade.” The film, purchased by Netflix, is scheduled for release in theaters this fall.

The Oxygen channel recently devoted an episode of its series “Snapped” to Bundy.

And USA Today posted four stories about Bundy at the top of its home page on Friday. One article centered on this tweet from Netflix’s official account: "I've seen a lot of talk about Ted Bundy’s alleged hotness and would like to gently remind everyone that there are literally THOUSANDS of hot men on the service–almost all of whom are not convicted serial murderers.”

No, Ted Bundy was not “hot.”

He was a cruelly manipulative narcissist. His crimes included the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach. He viciously beat to death two young women, Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy, in their Florida State University sorority house and brutally assaulted three other students. He reportedly practiced necrophilia on several of his victims and kept the severed heads of others as trophies.

But Netflix is trying to work both sides of an ugly and exploitative street. First, produce and promote a documentary about an infamous killer on the anniversary of his execution; second, snap up a fictional movie about the same psychopath that features a Hollywood hunk; and finally, react with shock on social media when viewers make the leap between violence and sex.

This isn’t the first time that the entertainment industry and the news media have portrayed Bundy as charming and sexy. In 1986, with Bundy still on Death Row, actor Mark Harmon, the Zac Efron of his day, starred as the murderer in a two-part TV movie, The Deliberate Stranger.

Seven years earlier, Bundy played a version of himself in the first nationally televised murder trial. Bundy, despite the presence of a court-appointed legal team, insisted on mounting his own defense. His courtroom antics fascinated TV viewers and more than 200 reporters who covered the proceedings.

At a second murder trial, six months later, Bundy pulled a stunt that further incited the public’s imagination. While questioning character witness Carole Ann Boone, a friend and former co-worker, Bundy asked her to marry him. She accepted, and later would say that Bundy was the father of her daughter, who was born while the killer was on Death Row.

Days before the execution, I was at my desk at a small South Florida newspaper when the Associated Press sent an advisory. Bundy had agreed to a press conference the day before the execution. A lottery would determine which reporters would attend. After talking to my editor, I entered and was notified that my name had been drawn. Then came a second notice. A smaller group of journalists had been selected from a second, unannounced drawing to witness the execution. I was on that list as well.

As it turned out, the press conference was cancelled. Bundy instead agreed to an exclusive interview with psychologist and radio talk show host James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family.

Bundy told Dobson that he took “full responsibility for all the things that I’ve done.” But he also claimed that his “addiction” to pornography “helped mold and shape” his violent behavior.

Much of what Bundy said in the interview about growing up in a “fine, solid Christian home” was false. But Dobson, who’d served on Attorney General Edwin Meese’s 1980s era Commission on Pornography, was a willingly gullible audience of one. Focus on the Family soon began hawking VHS copies of the Bundy interview as a warning to parents about the dangers of pornography.

For years, I was haunted by what I saw and heard on the day of the execution.

I was a young journalist who’d never seen a person die. I’d never even stepped inside a prison before that day. Still, the sober professionalism of the superintendent and guards, and the quiet respectfulness of the other witnesses, helped me to accept what I witnessed during the execution.

But nothing prepared me for what I encountered minutes later in a field outside the prison. While journalists descended a flight of outdoor stairs to leave the witness room, a wire service reporter raised a notebook above his head as a signal to a colleague outside the fence. The news flash was sent: Bundy was dead.

A chorus of booming cheers immediately rose from hundreds of bystanders who had gathered around the media camp across the road.

The other journalists and I piled into a van, and after exiting the prison gate, we were let out in the middle of the crowd.

Minutes after watching a person die, we stepped into a party. The crowd was laughing, cheering, eating and drinking.

Three decades later, I still carry an image in my mind of one excited middle-age woman who ran across the field in front of me. I’ll never forget the joy I saw on her face.

Many onlookers had brought home-made signs and banners. One of the milder ones read: “Ted Bundy. Goodbye. Good riddance.” Others wore T-shirts with slogans such as “Fry Day” and “Burn Bundy.”

I was appalled by what I witnessed in that field. I didn’t doubt then, or now, that Bundy deserved to be executed. His guilt was beyond doubt. He was manipulative and unremorseful to the end. But the death of another human being, no matter how vile, should be cause for reflection, not celebration.

Today, however, I’m less judgmental about the people who threw a party at an execution.

Entertainers and journalists had for years sold an irresistible story about a handsome and intelligent killer who disarmed victims with his charm. They turned Ted Bundy into a celebrity—a name and face nearly every American knew.

Who then can blame the audience for cheering when the villain meets his just end?

The truth, however, is that Bundy wasn’t particularly smart. A failed law school student, he turned down a plea deal that would have spared his life and twice served unsuccessfully as his own attorney in capital punishment cases. He certainly wasn’t as good-looking as the actors paid to portray him. His supposed charm was only one weapon he used to trap his victims. Sudden, overwhelming brutality was another.

As years passed, I thought less and less about Bundy and the day of his execution. A week or so ago, I spotted the documentary while scrolling through Netflix, but made a mental note not to watch. I wasn’t aware of the anniversary until reading the USA Today story about Bundy’s “alleged hotness.”

And I was appalled once more. This time because the cycle of media exploitation was happening again.

If the current barrage of TV shows and news stories have triggered in me memories I wanted to leave behind, what have they done to the victims who survived Bundy’s brutality? What dark memories have resurfaced for the families and friends of those he killed? When will they ever be allowed to leave a horrific past in the past?

Hours after the execution, the images of the day still swirling in my mind, I wrote these words to open a column published by the Scripps Howard News Service:

“I came here this week fearing what I might see when Ted Bundy was strapped into the electric chair. But I also went as an arrogant and vain journalist, hoping that I might through talent and insight find great truths about life in the spectacle of a man’s death. One truth I found is that death strips away all such pretensions.”

I wouldn’t change those words now. There is still no truth to be found in Bundy’s life or death.

But I would add this: Ted Bundy’s victims and their families deserve to be remembered and mourned.

The man who caused so much pain and grief should be forgotten.