In 1960, when he was working as a writer and sometimes performer on The Dinah Shore Chevy Show, Carl Reiner was contacted about being featured in an episode of This Is Your Life. The idea turned his stomach.

As a comedian at the end of his fabled run on revue shows, he knew it was his job was to make fun of shows like This Is Your Life, as he famously had years earlier in a sketch he wrote for Your Show of Shows—not appear on them. But the producers were insistent, offering at first a new car—he had just purchased one—and then a 12-volume leather-bound edition of the collected works of Mark Twain, his literary and comedy idol. The volumes included the author's signature and an original manuscript page. It was an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Reiner, who died Monday night at age 98 of natural causes, was the rare actor, writer, and comedian whose work as a humorist across a show business career that spanned nine decades could arguably rival that of Twain. His death was confirmed to Variety by his assistant, that publication reported Tuesday.

On Saturday, he posted a touching tweet about how he lived “the best life possible” with his wife and their three children.

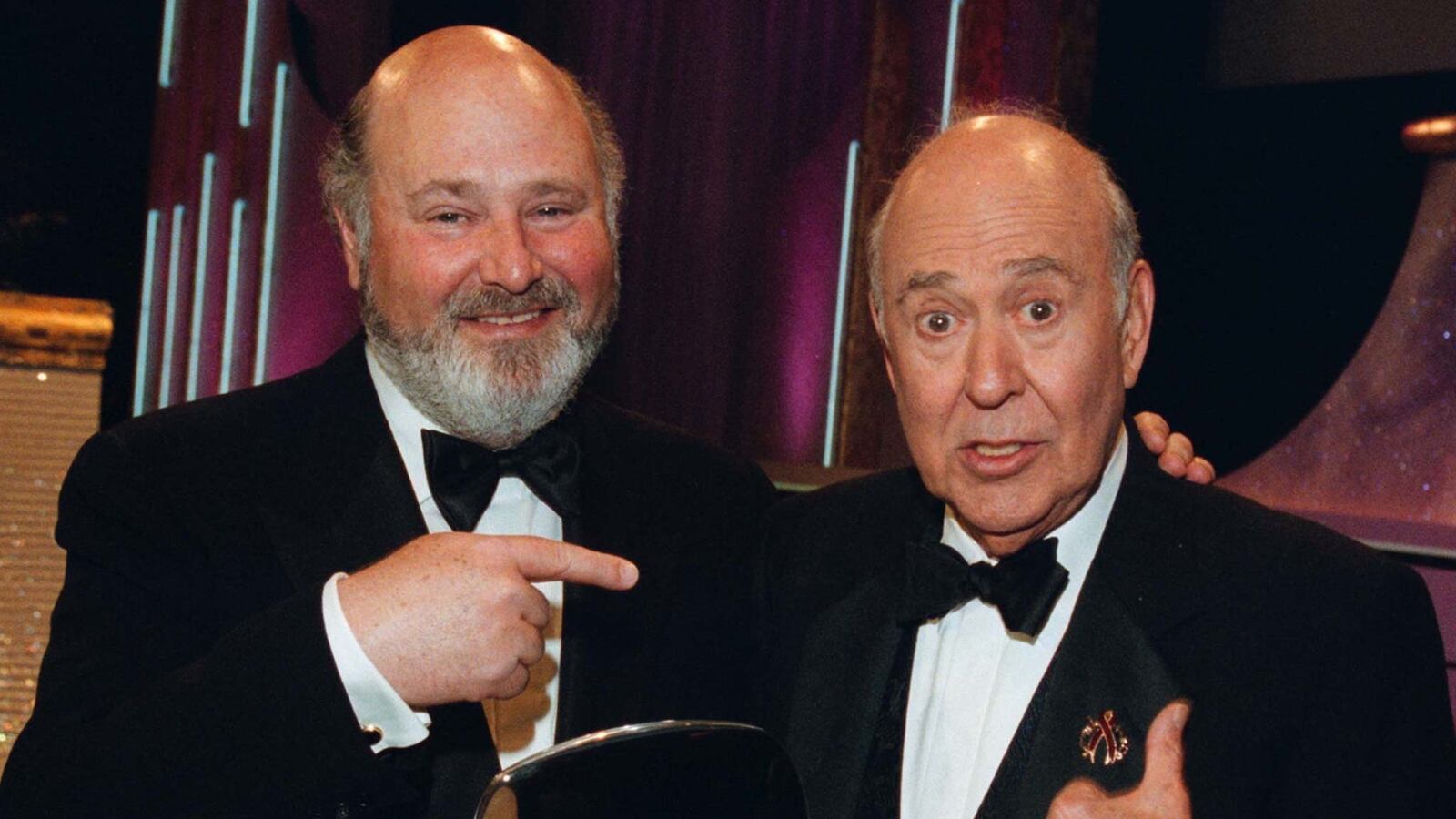

His son Rob Reiner, also a prolific actor/director and Twitter user, acknowledged his family’s loss this morning:

While he was rooted in the classic comedy of New York and the Berkshires, Carl Reiner’s take on the profession was decidedly postmodern. His comedy was observational in a manner later perfected by Jerry Seinfeld, literary and absurd in a way that presaged his frequent collaborator Steve Martin, and probingly conversational in a way that that predated just about every comedy podcast out there. A TV innovator whose work as creator and costar of The Dick Van Dyke Show proved the potential of the sitcom format, Reiner’s comedy was both cutting-edge and timeless, postmodern and classic. These qualities were perhaps best exemplified by his 2000 Year Old Man, a routine he created with longtime best friend Mel Brooks when they were officemates; by his countless talk show appearances—where he managed to bust through the phoniness of the set-up; and by his Twitter stream, where he entertained hundreds of thousands of followers with anti-Trump bon mots.

More recently Reiner found humor in his own and others’ longevity, and spearheaded the HBO documentary If You Are Not in the Obit, Eat Breakfast, which premiered in May 2017 and featured the town’s fellow old-timers Brooks, Van Dyke, Betty White, Kirk Douglas, and Norman Lear. In 2014, when Reiner picked up a copy of the Los Angeles Times and saw a picture of himself in the obits page in a tuxedo picking up one of the 10 Emmys he had won, he thought his time was up. (It turned out that the deceased wasn’t him, but Polly Bergen). “I was pretty sure I was not dead, because I had just come down a flight of stairs and was picking up the newspaper and putting together my cereal,” Reiner told KPCC in April 2017. “I think having something to do when you get up keeps you living, and people who are in show business are always in show business.”

Part of Reiner’s aversion to doing This Is Your Life was that it hadn’t, in his mind, been a terribly extraordinary life. He didn’t drink, never tried drugs, and didn’t chase women. And he never liked to look back. Even as a child, he was in a hurry, skipping the first grade and taking rapid advancement classes in junior high—not that his grades were much to speak of. He graduated high school at 16 with an unimpressive 73 percent grade point average when you needed an 80 to get into college. So went to work as a shipping clerk for a respectable $12 a week. That might have been his life had his brother Charlie not told him about an ad he spotted in the paper that made him think of his kid brother, who always managed to make all the other kids laugh. “[It] said, ‘Free acting classes, WPA, 100th and Center Street, New York,’” Reiner told PBS Newshour in 2016.

By 20, Reiner was getting $10 a week to perform five nights at Allaben Acres, an adult summer camp in the Catskills. It was there that he met Estelle Lebost, the assistant of the camp's set designer, and asked her to a dance. They would marry in 1943 and stayed that way until she died at age 94 in 2008. (She lives on through eternity as the utterer of what the American Film Institute says is the 33rd greatest line in movie history—“I’ll have what she’s having”—courtesy of son Rob's When Harry Met Sally). While Rob, their eldest son, followed the old man into show business, daughter Annie became a psychoanalyst and youngest son Lucas a painter.

Initially trained as a serious actor, Reiner would find his comic voice during his three-and-a-half-year stint in the army, where characters like Monty, a talking dog that did celebrity impressions, had troops throughout the South Pacific in stitches. A year out of the military, he landed the lead role in first the touring and then the Broadway production of Call Me Mister, so he was already pretty famous when he started as Sid Caesar’s sidekick—first in nightclubs and then on television—in 1950. “I thought this guy was an extraordinary talent and being a second banana to such a massive first banana wasn’t a come down at all for me,” Reiner told Fresh Air in 1988. “I realized I was working with the best.”

Even though he was initially considered to be just an airhead actor by the writers on Your Show of Shows, it didn’t take Reiner long to commandeer a writing room that was filled with some of the sharpest comics of that generation, including Mel Brooks, who would become Reiner's other life partner. One day at work, Reiner, incensed after watching a TV newsman interview a guy who pretended to witness something he clearly hadn’t, turned to Brooks and said, “Here’s a man who was actually at the scene of the Crucifixion 2,000 years ago.” Brooks responded—doing an old Jewish guy who knew Jesus—“Yes, yes… Thin lad, wore sandals.”

Suddenly, they had stumbled onto the 2000 Year Old Man, perhaps the most elastic and inventive improv vehicle ever known. For 10 years, Reiner and Brooks did the act for friends at dinner parties before Steve Allen finally convinced them to record it before someone stole it from them. (While they didn’t end up winning the Grammy they were nominated for that year, they made up for it 50 years later when they won one for The 2000 Year Old Man in the Year 2000).

“I was always a big fan of Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner’s 2000 Year Old Man sketch: I think it’s one of the biggest influences on the podcast,” says Scott Aukerman, the host of Comedy Bang Bang. “You’d never say Carl Reiner was the funniest dude on there, because he’s just teeing it up, but he knows what questions to ask to lead to great improv.”

In 1959, Reiner published his first novel, Enter Laughing, a semi-autobiographical look at his early days in show business. He would mine his personal story again a year, later writing 13 scripts for Head of the Family, which had Reiner starring as Robbie Petrie, a writer on a comedy revue show that came home to a suburban life in New Rochelle, New York. When the pilot failed, producer Sheldon Leonard convinced Reiner to revisit the project with Van Dyke and Mary Tyler Moore in the leads. For the next five years, The Dick Van Dyke Show became a colossal success for CBS, bringing home 15 Emmys and setting the blueprint for everything from The Larry Sanders Show to Curb Your Enthusiasm.

As a film director, Reiner was all over the place. His work could be poignantly personal, like the screen adaptation of Enter Laughing (1967) and the unjustly overlooked musical Bert Rigby, You’re a Fool (1989). (“It was one of the best things that I did in my life and nobody ever saw it,” he told NPR.) He could also be broad to the point of comic absurdity, best exemplified by a singular four year run with Steve Martin that brought us The Jerk (1979), Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), The Man With Two Brains (1983), and All of Me (1984). He could also be plainly commercial as he was when he guided his friend George Burns to a $50 million plus domestic gross with Oh, God! (1977), quite a feat considering Reiner was an avowed atheist.

In the end, Reiner may be most remembered for the way he made every encounter with him memorable. It is a skill he put to great use as the yearly host of the Directors Guild Awards, a gig he held on to well into his nineties. One year, when someone said on stage that “there are no atheists in fox holes,” Reiner took great offense, and went off script to tell a moving story about a friend from World War II who took his lack of faith all the way to his end on the battlefield. Atheism, like comedy, was something Reiner took very seriously.

“I have a very different take on who God is,” Reiner told the Los Angeles Times in 2009. Man invented God because he needed him. God is us.”